Sober, that is the first impression of the new Barragán Gallery in Weil am Rhein. There are reproductions on white walls of old architecture magazines, plans, floor plans and sketches, mostly in black and white. There are also color photographs, but their format is surprisingly small. Almost as if you were a little afraid of the power that they could develop. Large and in color and in the original.

Don’t be afraid of colour: Luis Barragán and his office partner Raúl Ferrera developed the Valdés house in Monterrey from 1981-1986.

(Photo: Barragan Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

It is, after all, the work of Luis Barragán, the great painter of poetic color in 20th-century architecture. He often bathed his geometrically clear design language in bright pink, yellow and orange. In violet, blue and red. He gave the international style a coat of paint that embraced the codes of cool modernity with a sensuality that was unique and made it clear at first glance that someone was choosing their own path. Or not?

Graduated from an engineering school: Luis Barragán in 1963.

(Photo: Ursula Bernath/Barragan Foundation)

Luis Barragán, born in Guadalajara, Mexico in 1902 and died in Mexico City in 1988, is in a way the great unknown among the most famous architects of the last century. And that despite the fact that the son of wealthy landowners was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1980, the world’s most important architectural honor. Barragán was the second laureate ever to receive the award. He was followed in the 1980s by such illustrious names as Frank Gehry, Oscar Niemeyer and Gottfried Böhm. Anyone who received the prize had made it into the architecture Olympus. The award was followed by construction contracts, further honors and, above all, the almost unlimited admiration at the universities for a long time.

World-famous shot: the staircase in the library of Luis Barragán’s apartment building at 14 Calle Francisco Ramírez in Mexico City. Staged by his favorite photographer Armando Salas Portugal around 1951.

(Photo: Armando Salas Portugal/Barragan Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

That’s not the case with Luis Barragán. The few books that exist about the Mexican architect are mostly out of print and can only be bought at high prices in antiquarian bookshops. The last major exhibition that highlighted his work and toured the world was almost 20 years ago. Power to the four generations of architecture students whose engagement with Barragán is at least patchy. Why? This is a long, sometimes tragic, sometimes marked by disappointments storywhich not least revolves around a highly political question: Who has the right to administer cultural heritage – because that’s what it’s about for a figure like Barragán in architectural history, but also for a country like Mexico – i.e. to decide who is allowed to research it and who doesn’t?

“Nobody was interested in Mexico”

The small Barragan Foundation, based in Birsfelden near Basel, Switzerland, has been legally allowed to do this since 1995, and received the architect’s estate after it was sold by a gallery owner in New York. “Nobody was interested in Mexico,” says Martin Josephy. He is the curator of the Barragán Archives and has already worked as an assistant on the large Barragán exhibition in the early 2000s. Since then, the art historian has devoted himself to “researching the archive”. One immediately believes that Josephy knows the archive “inside and out”. The Barragan Foundation went “really deep” and “came amazingly far” in analyzing Barragán’s work, for which they have now identified 170 projects, almost all in Mexico.

The processing of an architect’s estate means a lot of work. Detailed view from the Barragán archive.

(Photo: Lake Verea/Barragan Foundation)

And therein lies the problem. While Barragán’s architectural work was meticulously reviewed in Birsfelden, freehand sketches compared, correspondence studied and photographic perspectives analyzed by Armando Salas Portugal, the architect’s favorite photographer, whose estate the Foundation also owns, the rest of the world, especially Mexico, had a hard time , hardly any access to it. Work is being done on digitizing the archive, but so far “the database is still rudimentary,” admits Josephy. “People always think that computers can be operated at the push of a button, but you have to do that too.” Above all: “Wrong database entries reproduce themselves.” This is the honorable attitude of an art historian who wants to do everything correctly, but overlooks the fact that the Foundation has made it difficult to examine Luis Barragán’s work for years. What is not digitized today is not researched. Especially when it means that a Mexican architecture student has to come to Switzerland to do it.

Barragán was a master of light and thus an inspiration for subsequent architects such as Tadao Ando. Chapel of the Capuchin Convent in Tlalpan, Mexico City, 1954-1963.

(Photo: Armando Salas Portugal/Barragan Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

“We are not happy that it took so long,” says Martin Josephy. For years they have been announcing the publication of Luis Barragán’s catalog raisonné for “next year”, but it has still not been published. “It’s like Pandora’s box: when you open it, a lot comes out.” The original plan was to show one or two images for each project by Luis Barragán, but now the aim is to show everything there is about the respective project. The “ominous book”, as Josephy calls it himself, has now grown to 2000 pages.

Apparently brought modernism to Mexico: the architect Barragán, here a visualization of the motorway exit, 1957-1962.

(Photo: Barragan Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

And that’s why it’s important news that the Barragán archives – which include 13,500 drawings, plans and documents, as well as a photo collection of about the same size and a number of models, furniture and objects – belong in the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, making it accessible to the public for the first time. “We want to be the center of Barragánism,” says archivist Matthias Pühl, who will now deal with the estate, archive inquiries and digitization.

Connected to the two exhibition rooms is a study room for researchers and an archive room, where the originals from the architects’ estate of the Barragán and Ferrera offices are stored in leprechaun blue wooden cabinets, while the photographs by Armando Salas Portugal are still waiting in moving boxes to be reinterpreted. It was above all the stagings by this photographer that made Barragán “iconic and earned him the Pritzker Prize,” says Pühl.

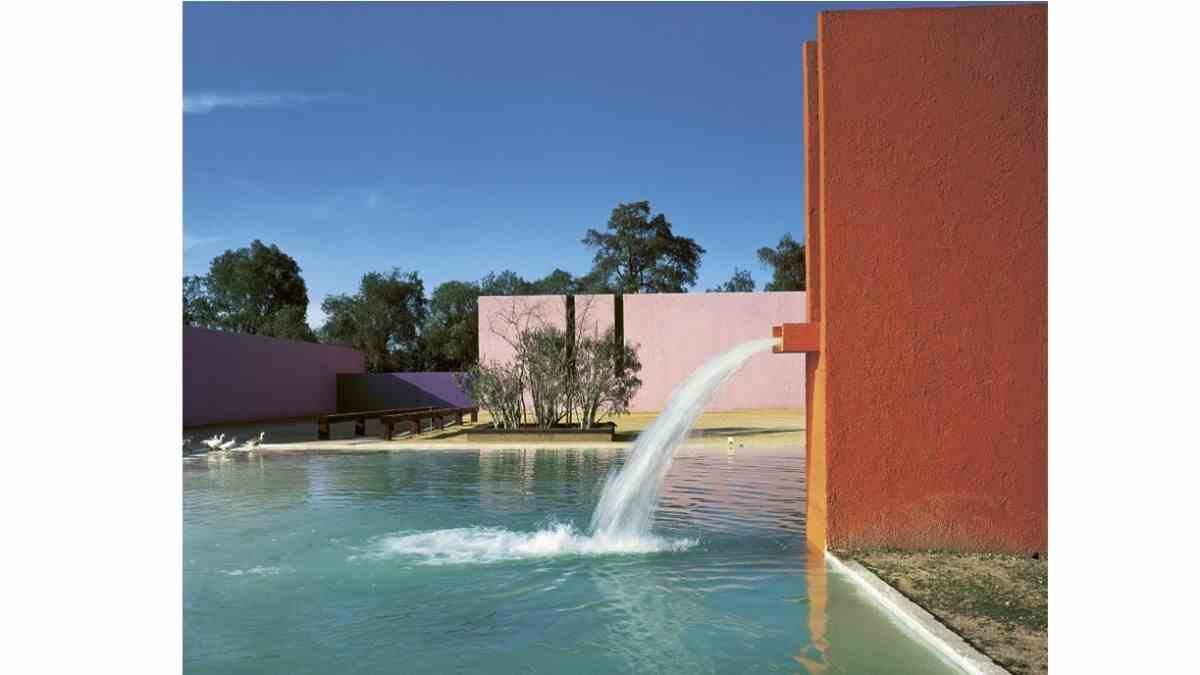

“Potential to become a hit”: the courtyard with horses and granary in the background by Luis Barragán and Andrés Casillas from the 1960s.

(Photo: Armando Salas Portugal/Barragan Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

Barragán has “the potential to be a hit,” says Josephy Martin, “but that’s just one facet and not the whole Barragán.” One can look forward to what the world will one day discover in this study room, but above all in a digital archive.