How can reality be represented? In the early 19th century, case history was the process by which medical and scientific knowledge was gathered. Today, their narrative and often straightforward classifying style would be more likely to be attributed to literature. The reports by the naturalists, Alexander von Humboldt, Georg Forster, Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin, read like literature. Their real purpose, however, was to describe and understand rules, laws and mechanisms in nature – which worked out quite well. Far from all, but an astonishing number of the findings of the naturalists of the 19th century are still valid today.

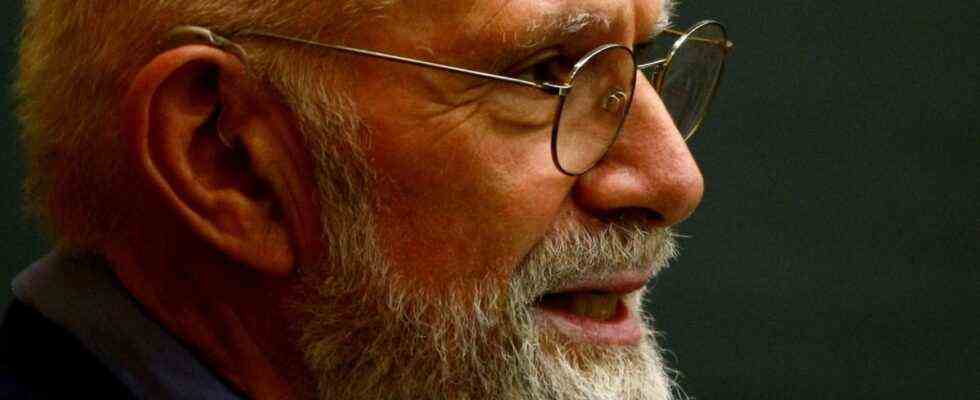

However, anyone who still tries to work scientifically in this way makes himself suspicious, if not completely impossible. One such person was the neuromedicist and writer Oliver Sacks, who died in 2015. “In fact, as a doctor, I am a nineteenth-century naturalist,” he once said to the journalist Lawrence Weschler, who accompanied him for several years in the early 1980s.

He was also interested in drugs and bodybuilding and did both to excess

Weschler went traveling with Sacks and interviewed friends and companions to write a biography of this Oxford-trained doctor who on the side manically wrote thousands of pages on all sorts of subjects, many of which became books and some even bestsellers; who was interested in drugs and bodybuilding and also drove both to excess; who went on motorcycle tours for days in a frenzy and devoted himself to ferns and their subgenus with the same enthusiasm, which, by the way, he was talking about also wrote a book.

“He was strange (…): huge, with a full beard, black leather jacket over a t-shirt with holes in it, large shoes, trousers that looked as if they would slip down at any moment. He was completely eccentric. He was dismissed several times and reinstated the same day – in part because the home was run by a director who was becoming increasingly senile. In his first stint at Beth Abraham, Oliver was still using drugs, albeit less and less. He no doubt had an addiction: ‘If one is good, three are better.’ He was very conscientious and very, very careful with his patients – in stark contrast to the way he treated himself. ” This is how Sacks is described by his former colleague Margie Kohl Inglis, with whom he worked in the late sixties.

Lawrence Weschler: Oliver Sacks. A personal portrait. Translated from the English by Hainer Kober. Rowohlt, Hamburg 2021. 480 pages, 25 euros.

Sacks, who grew up in London in a Jewish household, fled to California after completing his studies, also to finally live out his homosexuality, and finally ended up as a doctor and author in New York, really offended everyone. But at the same time he found people everywhere who were charmed by his idiosyncratic manner. Hardly any of Weschler’s interlocutors came to an unequivocal judgment about Sacks, their observations are always ambivalent, sometimes contradicting.

He made himself suspicious of his colleagues in medicine with books such as “Awakenings” about sleeping sickness patients, because pure case histories are not very relevant to empirical research, which needs as much data as possible. The fact that Sacks was often able to use conventional medication to help patients was often overlooked. Also, that listening and observing, the conscientious and thorough anamnesis, i.e. Sack’s central methods, are once again understood as essential tasks of the medical profession today. It is certainly not an exaggeration to say that the compassionate Sacks was way ahead of his time here.

Weschler, on the other hand, faced the same problems with his biography, now published in German, as the narrative neurologist Sacks: How should a person with a life that is dissolute in all directions, often unbelievable, be packed into a single book? Do you do it justice if you write in the same chapter about motorcycle gangs, drug abuse, bodybuilding, medical visits and literature, as if these were all ultimately similar stages in a life? In any case, Weschler decided against it, consciously or not.

Sacks himself often has his say; large parts of the book are actually less a biography than an autobiography

His book about Sacks is not a finely prepared and certainly not a chronologically narrated biography. It’s more like a collection of sources. Observations stand alongside conversations with companions, including Sacks of British publishers, friends of the family and former fellow students. Sacks himself also often has a say, large parts of the book are actually less a biography than an autobiography, because entire chapters consist primarily of Sacks quotations.

With this unusual, sometimes strenuous and confusing, but never boring form, Weschler made the right decision. Could he have brought his material into a more orderly form? Even Alexander von Humboldt’s late work “Kosmos”, with which he wanted to give a comprehensive “Physical Description of the World”, became increasingly difficult to understand towards the end, which led some literary scholars to the thesis that this could not simply be due to the advanced age of Humboldt at the time of writing , but rather be a principle: some things cannot be mapped in a very clear and structured way.

Weschler also sees himself as a natural scientist, as he once threw Sacks on the head in an argument. He had told him that, like a voyeur, he was only interested in his private life. Sacks therapist Leonard Shengold finally reassures the biographer and explains the outbreak: “Don’t you notice? she was his personal life. “This is either the greatest compliment or bankruptcy for a biographer.

In other words: If you are only interested in the very hard facts of this life, what Oliver Sacks did when, where and with whom, Wikipedia is more recommended. But if you want to know why this unusual person did what he did; how he was perceived, what he thought and what he doubted; what he suffered from and what he was happy about; what effect he had on his environment, how he worked, lived and wrote; in short: what Oliver Sacks could have been like – this book is recommended to him.