On March 5, 1933, 36.6 percent of those eligible to vote in the city of Münster voted for the Center Party. In Münster-Land it was even 50.7 percent. The numbers for the NSDAP lagged behind. The center tower turned out to be stable. It was precisely in this situation, however, that an initiative arose in Münster in favor of the NSDAP, which had remained in the minority, a campaign carried out by Catholic academics who were looking for similarities between Catholicism and National Socialism. Professors Michael Schmaus and Joseph Lortz as well as the freelance writer Josef Pieper formed the forefront of this movement, which soon made a name for itself in other places too; contemporaries called the authors “bridge builders”.

Kurt Flasch, a tried and tested medieval researcher but also a subtle explorer of contemporary intellectual life, met these three men while they were still alive and followed their path in detail. They were highly respected and award-winning personalities in post-war Germany. Internally, at least, they had distanced themselves from their errors. “I found a friendly way to get along with Schmaus, a normal job with Pieper, and nothing at all with Lortz,” writes Flasch. Just like in this short formula, the accents in the short, exciting script of the renowned essayist are missing: About Schmaus, who was professor of Catholic dogmatics at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich after the war and until his retirement in 1965, and in the meantime even LMU rector, Flasch lectures rather cautiously; He tries “relatively benevolently” to explain his “lack of a sense of reality”; the representation is covered over by ironic lights at one point. At Pieper, Flasch undertakes an in-depth analysis of his thoughts on labor law and social policy, positions that in part go back to Pieper’s doctoral supervisor Johann Plenge and which for a short while bring him close to the Nazi ideology. With Lortz, on the other hand, who taught church history at the University of Mainz from 1950 until his death in 1975, Flasch started a general accounting, whereby he did not omit the writings on the history of the Reformation, which later made the church historian internationally famous.

Lortz argued that it should be easy for believing Christians to identify with Hitler, the anti-modern

Where did the “bridge builders” see similarities between National Socialism and the Catholic world? In the first place it was probably a combative anti-liberalism that united both, the aggressive turn against the modern, emancipated, individualized world. Believing Christians should be able to identify with Hitler, the anti-modern, easily – Joseph Lortz in particular advocated this. Order and community, leadership and ties should come to the fore again – a “völkisch order of life” should replace the vague internationalism, which did not oblige, but let the people and the state take a back seat.

As Medievalists, the three authors often oriented themselves towards a fictitious Middle Ages. They had in mind a hierarchically strict, barriers-setting church – a counterpart to the equally strict, spirits-restraining state. “Anyone who loved the restoratively reconstructed church described in this way with gripped carelessness, who, like Lortz, praised the condemnation of freedom of conscience by the popes, could probably find it related to the Third Reich in its early stages.”

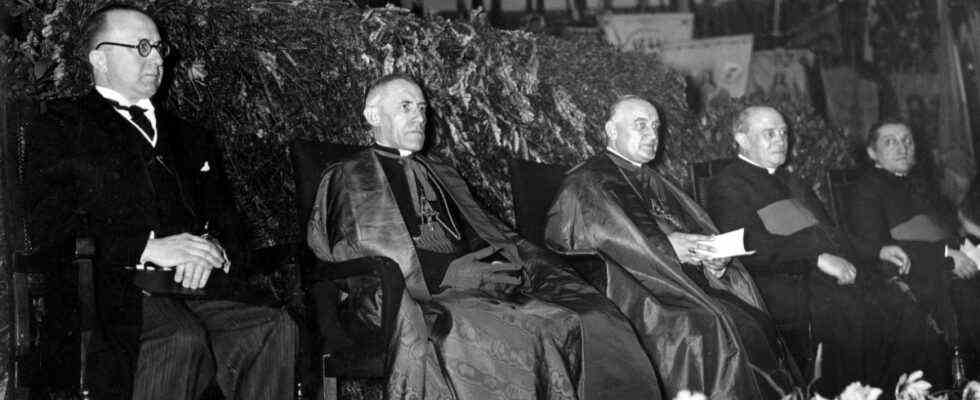

Lack of a sense of reality: After the Second World War, Michael Schmaus was Professor of Catholic Dogmatics at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich from 1946 until his retirement in 1965, of which he was also Rector in 1951 and 1952.

(Photo: University Archives LMU Munich)

For us later, who know the outcome, the initial confidence of the three authors in Hitler, their hope that the good (read conservative) forces would prevail against SA thugs and SS conspirators, is difficult to understand. Could the “bridge builders” not imagine the later crimes of National Socialism in its beginnings? Did they ignore what was already clearly visible at the beginning: the dismantling of the constitutional order, the tendency towards one party to rule, the blows against the opposition, the boycott of Jewish businesses?

The situation in the summer of 1933 was certainly ambivalent in some respects, contradicting phenomena had to be dealt with, and some things encouraged the “bridge builders” to be optimistic. For example the fact that the Bavarian (Protestant) minister of education and Nazi Gauleiter Hans Schemm made school prayers compulsory and issued the slogan: “Our religion is called Christ, our politics is called Germany.” Or the temporary participation of Nazi organizations in church services and processions – and last but not least Hitler’s talk of “positive Christianity” as the basis of the Nazi state.

Condemnation of freedom of conscience: After the war, Joseph Lortz taught church history at the University of Mainz from 1950 until his death in 1975.

(Photo: Reiner Wierick / University Archives Mainz)

Quite a few Catholics clung to Hindenburg, the aged Reich President, and Franz von Papen, the Catholic Reich Vice Chancellor; they were seen as protective shields of Christian tradition. Of course, the anti-Christian counter-world under National Socialism – Rosenberg, Himmler – was also there, and it was gaining power from day to day. The criminal physiognomy of the Nazi state also emerged ever more openly. How could Catholics still look for legitimate access to the National Socialist worldview? Wasn’t that an illusion from the start? Indeed: “The process retains something puzzling. Perhaps the devil was at work,” is the remarkable conclusion of the avowed agnostic Kurt Flasch.

The group fell when Reich Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen was overthrown

Were they really “Catholic pioneers of National Socialism”, as Flasch’s book title says? I have objections here; they concern the word, the semantics of the process. At the moment, the Hohenzollern debate is differentiating and exacerbating our historical vocabulary. We ask more precisely how, in what way, since when and for how long contemporaries supported, promoted and advocated National Socialism. Clarifying this in detail is not only important in court, it also influences the formation of historical judgments.

That the authors mentioned “prepared the way” for National Socialism – Flasch refutes this assumption himself in several places in his book. He repeatedly speaks of the fact that they were “not trained to analyze political processes”, that they were “politically inexperienced professors”. How could they then pave the way for National Socialism? The Nazi leaders received no impetus or suggestions from the bridge builders. They couldn’t learn anything from them. Nowhere did they take a leadership role. They just followed.

Kurt Flasch: Catholic pioneers of National Socialism. Michael Schmaus, Joseph Lortz, Josef Pieper. Verlag Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2021. 192 pages, 25 euros.

And even if you take “trailblazers” in the narrower sense – as a guide especially for Catholics to National Socialism – the word leads nowhere. Because the “bridge builders” triggered a brief rumble in German Catholicism, but not a lasting movement. When the Reich Vice Chancellor was disempowered in 1934, the group fell into insignificance. Your publications remained isolated and almost ineffective. On the other hand, other Catholics, whom Flasch also mentions, judged correctly and consistently appropriate: Alois Dempf, Dietrich von Hildebrand, Gustav Gundlach, Waldemar Gurian.

Of course, that shouldn’t prevent anyone from reading this book. It would be the first book by Flasch that would have come to light without causing (useful) controversy. So the debate will go on, I think – the master and his readers right in the middle of it!