column

Great idea

How can you recover valuable phosphate from wastewater? Three students came up with an amazing solution.

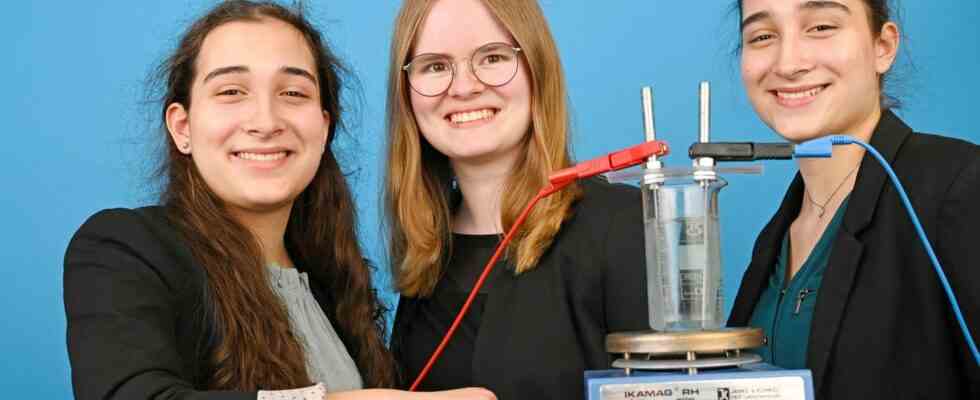

Hannah Amrhein (centre) and Lena and Hanna Fries were national winners at Jugend forscht with their project on phosphorus recycling using electroflotation in the chemistry category

© Cosmos

They say: wastewater is super exciting. Three schoolgirls have developed a new process that recycles up to 80 percent of the phosphates. And thus won at Jugend forscht.

For a long time, many of our friends didn’t know exactly what we were researching. Wastewater is not exactly an issue where everyone immediately says: “Tell me more!” But once you’re in the bubble, wastewater is super exciting.

We have developed a process that can be used to recover phosphates from wastewater. We came across this topic by accident. When we first applied to Jugend forscht three years ago, we wanted to do something with the environment. Because environmental protection is an important issue for our generation. We then came across an article that presented the principle of what is known as electroflotation – this is a process that can be used to purify water.

Recycling by electroflotation

The experimental setup is relatively easy: all you need is a beaker and a dye – such as methylene blue. But tea or ink will work too. Then you dip two paper clips, apply voltage, add table salt and stir the whole thing. The dye becomes trapped in flakes and drifts to the surface. The water that used to be blue suddenly becomes clean. It looks very cool and we were fascinated by it. We didn’t really understand the chemistry behind it at first, but our spirit of research was awakened.

Over the years we have dealt more and more intensively with electroflotation. We looked at which substances can be cleaned out of the water – and finally came to phosphate. The mineral is contained in fertilizers and is a very important nutrient for plants. But phosphates are a scarce and finite resource, which is why recovering them is so important.

To find out how this can be achieved, we used our biology teacher’s laboratory work station: Our teachers all have their own mobile table in the lab, and the biology teacher kindly sacrificed his for us. About once a week we worked there for about three to four hours.

We often went home with no real results. And there were moments where we were like, Huh? Just: Huh? Why did this happen now? For example, we carried out an experiment exactly as we did the week before, but suddenly a precipitate developed. Why? Most of the time we sat down and brainstormed how we could do it better. That motivated us to keep going.

Especially since our experiments eventually became more successful. We managed to recover over 80 percent of the phosphate with our method, which was the most blatant value that we achieved in the entire research series. Processes currently used in sewage treatment plants only achieve a recovery of 40 to 60 percent.

Jugend forscht winners: “It became clear to us that all three of us want to go into research later”

Of course, we would be delighted if the process we developed played a greater role in the future. But that would require more people to recognize the importance of phosphate recovery. To this day, the substance is partially incinerated. And that’s just a waste.

The nice thing about Jugend forscht is that in the competitions we met people who are just as enthusiastic about science as we are. We had a basic connection to the others from the very first moment. It became clear to us that all three of us want to go into research later.

In recent years we have learned to explain projects relatively quickly, to be brief and to present them in English. In September we were allowed to go to Leiden for the European Championships for young scientists. And when the email came that we could take part in an international research festival in the USA next year, we freaked out a bit. That is why we are particularly grateful to everyone who has supported us.