Parallels to SARS-CoV-2: Similar to the corona virus, flu can also promote dangerous thrombosis – even if it is not severe and only affects the lungs locally. This is now proven by experiments with mice. Accordingly, such a local influenza infection increasingly activates blood stem cells and causes a hasty formation of immature blood platelets. These tend to clump together and can thus promote thrombosis.

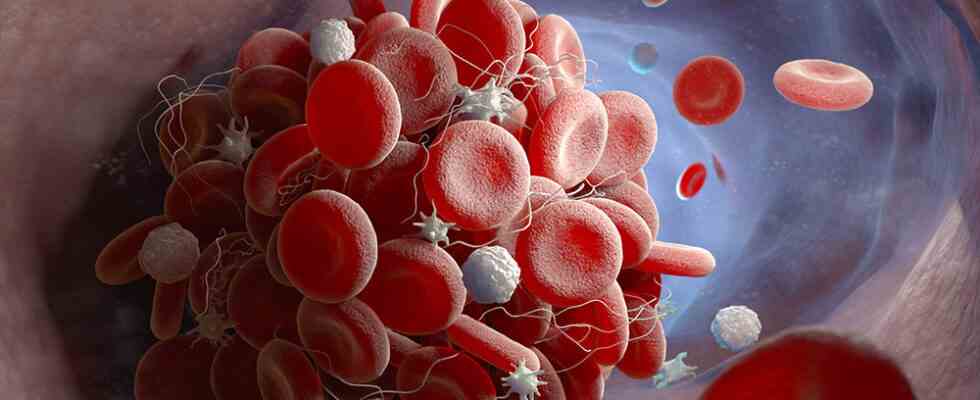

In the course of the corona pandemic, it has been shown that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus also affects the blood and the blood vessels influenced. Especially in severe cases of Covid-19, there are often inflammatory changes in the vessel walls and an increased tendency blood clots and thrombosis. The blood of seriously ill patients also contains an unusually large number immature progenitor cells platelets, so-called megakaryocytes, and red blood cells.

Similar changes in the blood can also occur in severe courses of influenza and other respiratory diseases – and increase the tendency to thrombosis. So far, however, it has been unclear which factors favor this and how severe the viral infection must be.

How does influenza affect the blood?

In order to find out exactly how an influenza infection affects blood formation and thrombosis, Marcel Rommel from the Paul Ehrlich Institute and his team have now carried out experiments on mice. They infected her with varying doses of the H1N1 flu virus. This variant also affects us humans in the course of annual flu waves. A group of mice had previously been vaccinated.

Over the next few days, the research team examined how many blood stem cells had been activated and how many had developed into platelets. With the help of further investigations such as bone marrow transplants and in vitro tests, they also got to the bottom of the mechanism behind the measured platelet concentrations.

First too few platelets, then abnormally many

The result: In the first three days of the acute flu infection, the number of thrombocytes in the blood of the mice initially decreased. This is also typical for human influenza patients, as the researchers explain. In the event of an infection, the thrombocytes actively migrate to the site of the inflammation and attach themselves to pathogens there. In this way, they hold onto the germs until scavenger cells appear and finally eliminate the clumps of pathogens and platelets. The platelets are therefore “used up” in large quantities in the first few days of an illness.

This means that the body has to produce new platelets quickly. This could also be seen in the blood of the mice. After the first three days of their flu infection, the number of platelets increased rapidly and even exceeded the amount that was in the blood before the infection, as Rommel and his colleagues found.

Intermediate steps of blood formation skipped

But how is it possible for the new blood platelets to form so unusually quickly? The research team found that the blood stem cells of infected mice skip several steps in their development into platelets. This was recognizable from a subset of blood stem cells that carried typical markers of megakaryocytes. The blood stem cells therefore developed directly into these platelet progenitor cells and these then into immature platelets.

In this way, the thrombocytes formed in the mice suffering from the flu omit several precursor stages. As a result, they look different from normal platelets and are larger, immature and quicker to activate. The “rushed” process in which they arise is called emergency megakaryopoiesis. This has indeed already been described before. But until now it was not known that it also occurs in connection with local viral respiratory diseases such as influenza.

Strength of reaction dependent on viral load

It turned out that the extent of the emergency megakaryopoiesis in the mice was related to the viral load: the more influenza viruses had infected the lungs, the more activated blood stem cells the scientists found. In contrast, in mice that were injected with only a small dose of the virus, the stem cells were only activated with a delay. After these mice survived the disease, their blood stem cells became inactive again and returned to the quiescent phase.

The researchers attribute the fact that the blood stem cells wake up from their dormant phase and suddenly become platelets to two cytokines. These cell messenger substances promote inflammation, but also influence the differentiation of cells. In the mice in the experiment, the team observed that the cytokines interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 made a key contribution in activating blood stem cells and triggering emergency megakaryopoiesis.

Local infections as a new danger

These effects of the influenza infection on blood formation have both positive and negative consequences: on the one hand, the blood platelets that are produced in the course of emergency megakaryopoiesis are quickly available to fight the pathogens. On the other hand, they also bring a risk. Because they are larger, immature and more reactive than ordinary platelets, they increase the risk of blood clots and thus thrombosis, especially in the lungs.

Rommel’s research team was able to prove that local viral infections can also change blood formation and increase the risk of thrombosis. Previously, this was only known from infections affecting the entire body. (Cell Reports, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111447)

Source: Cell Reports