Paul Jackson comes from a working class background. When he was born in 1961, his father was ill, the family had little money, and then there was the period of great inflation in the 1970s. “I’ve seen what a lot of poor people are going through right now,” says Jackson, who is now chief strategist at investment firm Invesco. And he can give them little hope. “Unfortunately, the central banks are miles behind when it comes to fighting inflation.”

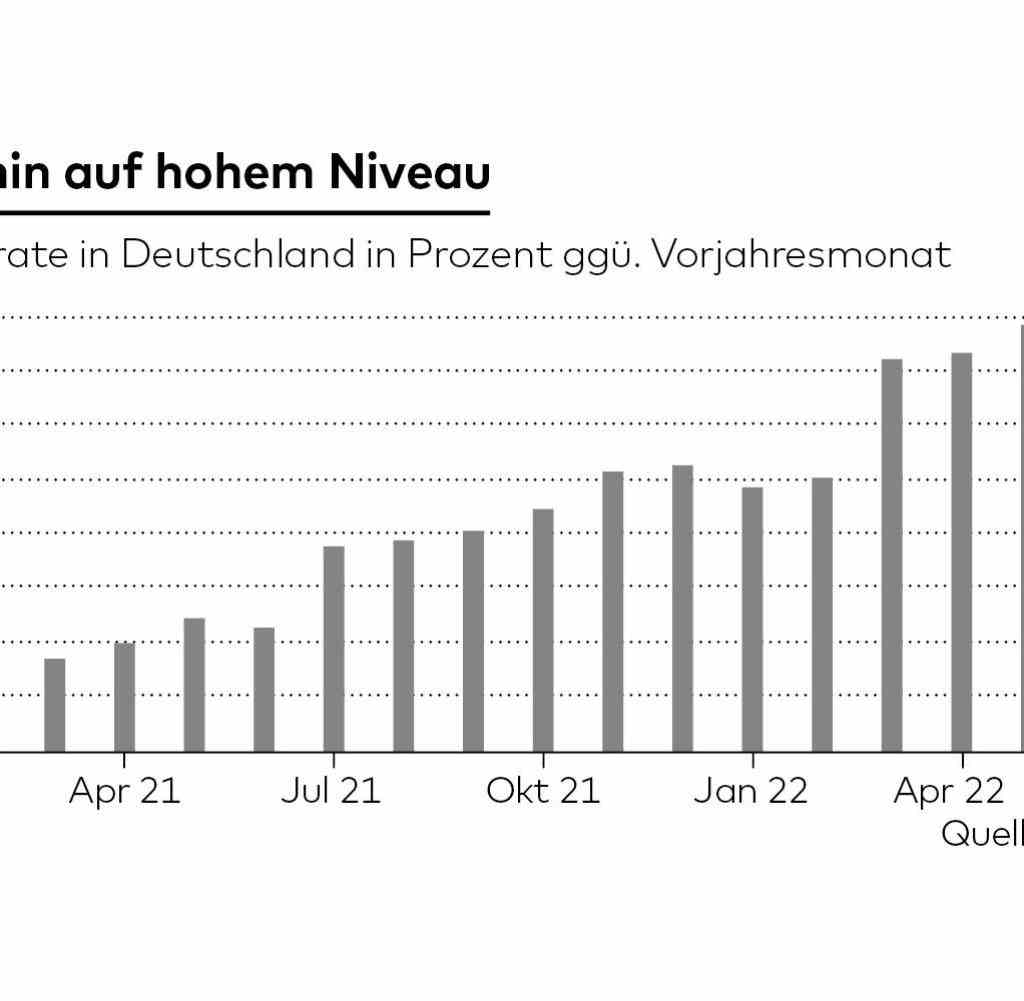

In the UK, where Jackson lives, the inflation rate just passed 10 percent. In Germany, it is still being depressed by measures such as the 9-euro ticket or the tank discount, but when these expire, similar rates are also possible in this country.

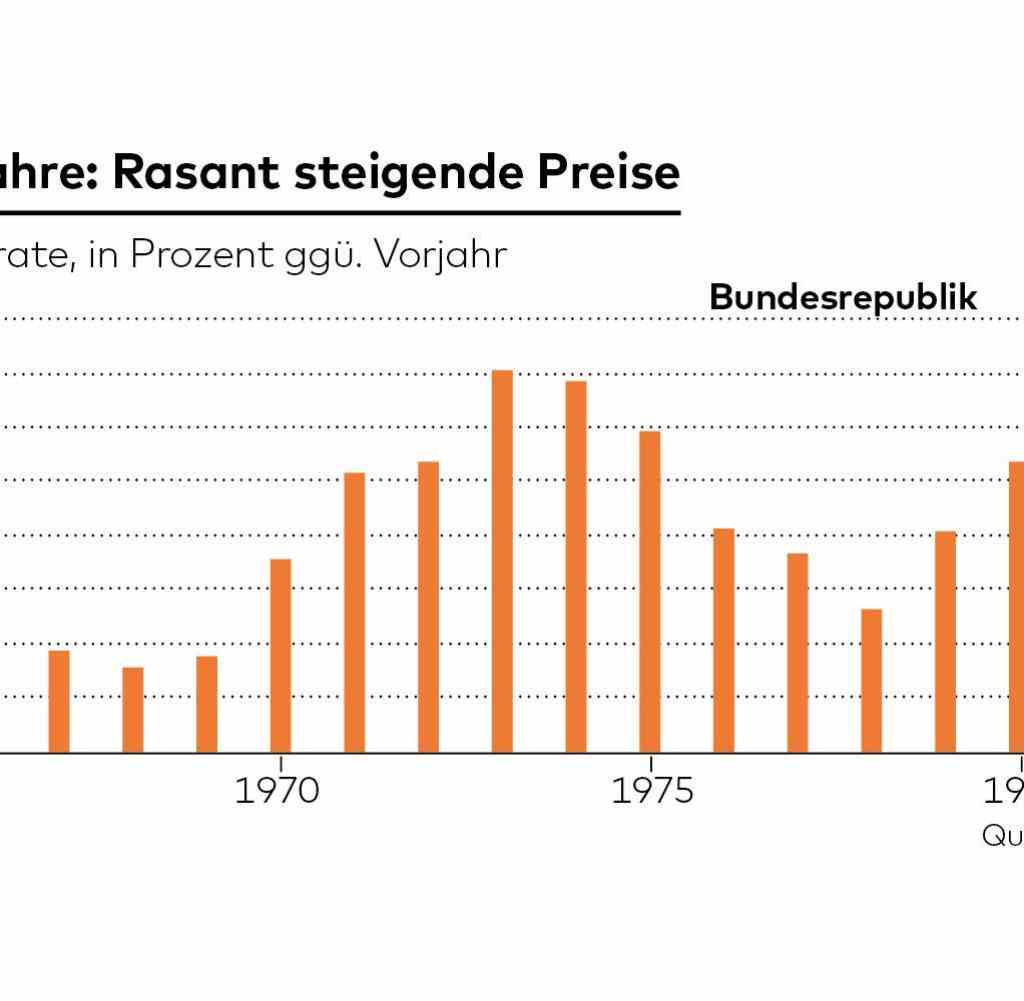

50 years ago, the wave of inflation could only be stopped by drastic measures: the US Federal Reserve increased the rate at the time policy rate up to 20 percent, triggering a deep recession. Is something like this necessary again today? Or will the previous, rather slight interest rate hikes in the USA and the euro zone be sufficient this time?

The latter is suggested by the fact that official inflation rates in most countries in the 1970s were far higher than they are today. However, this could be a sham, as a recent study by economists Marijn A. Bolhuis, Judd NL Cramer, and Lawrence H. Summers shows. The scientists have addressed the problem that inflation rates used to be measured differently than they are today. They have therefore recalculated the data in a uniform manner – and come to a frightening result.

“Our analysis reveals that current inflation, particularly core inflation, is significantly closer to previous peaks than official data suggests,” the authors write. Core inflation is the figure that results when energy and food prices are not included in the calculation. It is seen by economists as an indicator of how much inflation has already spread.

According to official data, US core inflation peaked at 13.6 percent in June 1980; it is currently reported at 5.9 percent – apparently far from the value at that time. However, according to the scientists’ recalculations, it was 9.1 percent in 1980, which would significantly shrink the difference.

“We need a similar rate of decline in inflation today”

In addition, inflation measurements at the time make the subsequent decline, fueled by sharp rate hikes under then Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, look stronger than it was. Instead of falling by eleven percentage points, the rate of inflation was only reduced by around five percentage points as a result of these measures. “To return to a core inflation rate of 2 percent today,” the economists write, “we need a drop in inflation of a similar magnitude to that achieved by Volcker.”

Historically, inflation is currently much more pronounced than most observers assume, and far more stringent measures are therefore needed than have been taken so far. Above all, they should have been seized sooner. “The US Federal Reserve should have reacted in mid-2021,” says Invesco strategist Jackson.

Instead, she let valuable time pass until March of this year. The European Central Bank (ECB) waited even longer and only increased interest rates for the first time last month. “Since the central banks reacted so late, they now have to act all the more aggressively.”

Source: Infographic WORLD

But obviously that’s not enough so far. This is shown by people’s so-called inflation expectations, which are determined in surveys. The Bundesbank only released this data for Germany on August 12 – and it is shocking. Accordingly, the Germans do not expect a decline for the next twelve months, but an average rate of seven to eight percent. Even looking at five years, they assume around five percent.

For Jörg Krämer, Chief Economist of the Commerzbank, that’s an alarm signal. “People expect higher inflation if they don’t believe that central banks are successful in fighting inflation,” he says. “And currently many no longer believe that.” This is not only due to the hesitant interest rate increases. “There was a crisis meeting of the ECB on the rising yields on Italian government bonds,” says Krämer. “To date, however, there has not been a crisis meeting on inflation.”

He also believes that interest rates would have to rise significantly further in order to get inflation under control. The key interest rate of the ECB is currently 0.5 percent. “The neutral interest rate would be 2.5 to three percent,” says Krämer. At this value, monetary policy would neither slow down nor fuel the economy. “Three to four percent would be necessary to get into an anti-inflation mode,” believes the Commerzbank expert.

Paradoxically, however, the financial market has come to believe in recent weeks that the worst of inflation is behind us. The reason for this was the slight decline in the inflation rate in the USA in July. Now the majority of investors believe that the US Federal Reserve will raise interest rates once or twice before the end of the year, but will already cut them again in the coming year. And for the ECB, too, they are assuming a maximum of one or two slight increases before the Europeans turn around again.

The consequence of this will be that Germany will have to live with high inflation rates for years to come, Kramer fears. “Inflation is entrenching and not going away on its own,” he says. This does not mean hyperinflation under any circumstances, but rates of four to five percent could become normal.

Unless everything is different than it was 50 years ago. And indeed there are indications of this, because despite all the similarities between then and now, there are also many differences. “Back then, inflation was driven even more strongly by energy prices,” says Paul Jackson. This was triggered by the OPEC oil price increases, but ultimately it was due to an enormous surge in demand due to the population explosion since the 1950s. In the meantime, however, the population is shrinking, and the demand for energy will tend to decline.

Source: Infographic WORLD

“Also, workers had much stronger bargaining power back then,” says Jackson. In Germany, 32 percent of employees were union members in 1970, since then the proportion has shrunk to half. “This makes it much more difficult for employees to fight for wage compensation, the wage-price spiral is turning more slowly today than it was 50 years ago.”

However, if price increases are not offset by corresponding increases in wages, workers will inevitably have to save. They can afford fewer goods and services. “This in turn will lead to a drop in demand,” says the investment expert, “which then triggers a recession.” In this way, inflation sows the seeds for its own decline.

This would then be achieved in a different way than at the end of the 1970s, but it would not be any less painful. Especially not for workers, employees and the poorest sections of society.

“Everything on shares” is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with our financial journalists. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music and deezer. Or directly by RSS feed.