As Evelyn Richter for the women’s newspaper in the early 1980s To you was allowed to photograph Saxon worsted spinners, the result was, well, too realistic for the cultural functionaries of socialist realism: Richter had dared to show the truth on her black and white photos, very hard work, bitter poverty in front of hopelessly outdated machines. So the whole series in the magazine was quickly spruced up with fat clover-leaf borders.

The anecdote symbolizes in a grotesque way Evelyn Richter’s relationship to the official art doctrine of the GDR. The series is an exception in that Richter was hardly ever allowed to publish anything, for decades she had to stay afloat as an advertising photographer and photo editor for trade fairs. And when something was allowed to appear, there was usually trouble. Her actual works, the worker portraits and long-term observations of artists, she produced, as she herself laconically put it, “for the box”. In these boxes, however, reality has accumulated like sediments over the decades.

As a daughter from a middle-class family, Evelyn Richter, born in 1930, had no chance of a place at university in the early GDR. She did an apprenticeship with the portrait photographer Pan Walther, was then allowed to study at the Leipzig University of Graphics and Book Art, but was kicked out after two years because the university officials found their fellow student portraits too defeatist. After all, art should show what should be, not what really was.

Right from the start, Richter refused to accept this official iconography of the New Man; her black-and-white recordings counteracted any propaganda of the upheaval. Shift workers going home on the Leipzig tram, tiredness like a smell hanging in their heavy clothes; Empty industrial landscapes or prefabricated buildings on a moon-bare earth. Some of her pictures have a quiet comedy in the clash between the assertion of state propaganda and the depressing reality: “Entrance to the nursing home” from 1986 shows a painting of Lenin in the center, gold-framed on a faded wallpaper, he enthusiastically speaking to the sky, his head fluffed around it Holy shine. Below the picture is the wobbly trundle bed of a retirement home, the linen sheet looks like a shroud. GDR in its final stages.

Richter’s awakening experience at the end of the 1950s was Edward Steichen’s world touring exhibition “The Family of Man”, which also stopped in West Berlin. She often quoted Egon Erwin Kisch’s sentence that nothing is more sensational than the truth, and always added that the truth is reality. “But reality can be manipulated,” she knew. “That is why authorship is so important. You vouch for your work with your name.” The black edge of the negative surrounds your enlargements like a kind of stamp: Nothing has been zoomed in here, the picture was created exactly that way.

She was looking for the “moment of concentration”. Some recordings took her weeks

Evelyn Richter always worked with the inconspicuous, light 35mm camera, for decades she always carried her beloved Leica around with her, after all, you never know when the “moment décisif” will come, as Cartier-Bresson called it. She preferred to speak of the “moment of concentration” in which everything comes together. The 35mm camera accommodated her insofar as she liked to work inconspicuously, out of the situation, whereby she expressly protested against the “fashionable term of moment photography”, which in her eyes was “a single misunderstanding”. Your recordings, no matter how often they owe them to everyday situations, almost always have something condensed, strictly composed. Some photos took her weeks. In 1975 she is said to have streamed through the eighth GDR art exhibition for a fortnight until she finally managed to take one picture: In front of Wolfgang Mattheuer’s painting “The Excellent” stands a tired, disaffected visitor. The photo is a double negation of the officially decreed optimism of the state, the excellent woman in Mattheuer’s picture sits with empty eyes in front of her withered bouquet of tulips, the visitor to the exhibition seems to be her worn-out sister in the gray everyday life.

Life as a photographic dissident was not easy; in terms of her work, she repeatedly compared herself to a partisan. In 1980 she was given a lectureship in photography at the College of Graphics and Book Art and was perhaps the most influential photographer in this position for future generations.

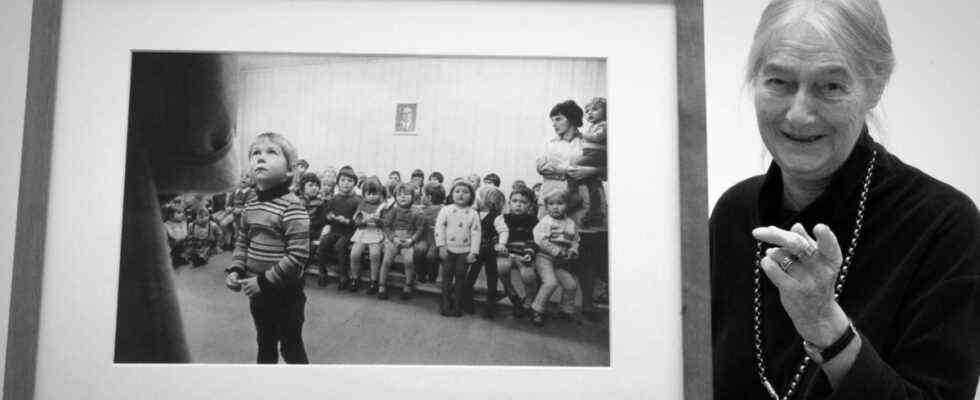

Richter must have been blessed with a great gift of friendship, there are many long-term companions and companions of destiny. She was also a lifelong traveler, there are series from Moscow, Venice, New York, Romania. In 2010 she handed over a selection of 730 pictures to the Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts as a preliminary. In 2013, when moving in the proverbial “boxes”, another 70 miniature films appeared, from which her student and friend Werner Lieberknecht composed the wonderful volume “Von der Latenz der Bilder” in close cooperation with her. On her 90th birthday, the Dresden Albertinum showed her life’s work. Evelyn Richter died last Sunday at the age of 91.

© SZ / CD