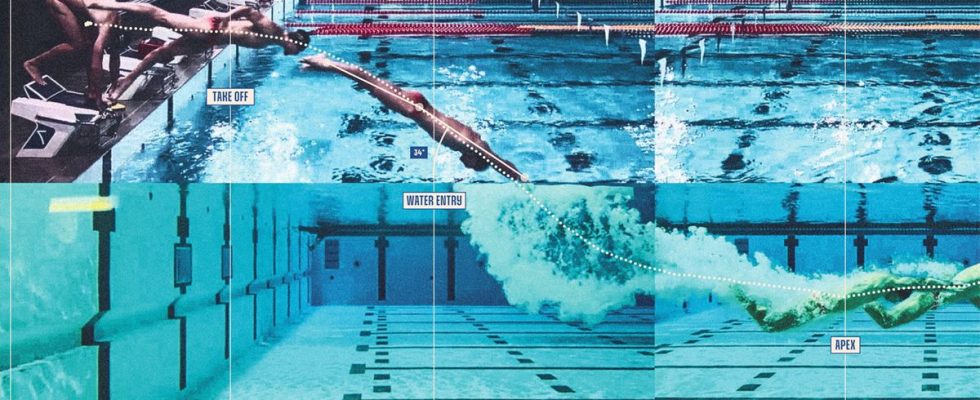

The photo had its place on the walls of Insep, at the Palais des Congrès and at the Musée de l’Homme, in Paris. We can even speak of a fresco as it is so imposing. It represents the departure of a swimmer, frame by frame, from his dive to his rise to the surface of the water, annotated by a whole bunch of indications which seem a little barbaric at first glance. This swimmer is not just anyone: it is Maxime Grousset, five-time world medalist including twice over 100m freestylecurrently refining his start before the world championships in Fukuoka last July.

An admirable image for its aesthetics, but not only that. It also perfectly illustrates the work carried out for four years now by the French Swimming Federation in the scientific field to support its swimmers. And prepare them as best as possible in view of the 2024 Olympic Games.

The alliance between swimming and scientific research was a little slow to arrive in France, compared to what has been happening for a while among the Anglo-Saxons. But she is quickly catching up. Initiated by the “Sciences 2024” plan, launched in 2018, this connection really gained momentum with the launch of the “NePTUNE” project, one of the 12 selected by the National Research Agency and the CNRS as part of the priority research program (PPR) “Very high performance sport”, at the very beginning of 2020. Its objective? Provide French coaches and swimmers with tools to optimize performance, thanks to a very detailed analysis of athletes’ movements and their impact on swimming speed.

20 cameras installed along the Insep basin

Let’s take the example of sprinters (50m and 100m), a population that has the most to gain from analyzing each movement, when we know that their races are decided to the hundredth of a second. Most of the research has focused on the start and the turns, the two moments that make the difference because at very high levels, athletes all swim at approximately the same speed. Coach Michel Chrétien, head of the “swimming race” group at Insep, was very involved in this project with his flock, and in particular his leader, Maxime Grousset. “One of the first questions he asked us was: ‘When should you start the ripples after entering the water?’ », says Rémi Carmigniani, researcher at the Ecole des Ponts ParisTech and responsible for these two strategic aspects of the project.

The scientists then filmed several departures from Grousset, using 20 cameras installed especially for this program along the National Sports Institute pool (10 on the surface, 10 underwater, every 5 meters). By comparing speed, frequency and amplitude data, they were able to determine, with the help of their trainer, the optimal timing, combining good depth and good speed when triggering. Then came the question of the length of the casting.

Fewer pours, more speed?

Popular belief is that it must be as long as possible, as close as possible to the regulatory 15 meters, because we move faster underwater than on the surface. “Well no, that’s not true for all swimmers,” Rémi Carmigniani tells us, one of whose specialties is fluid mechanics. Some people don’t move any faster underwater. We generally say that this is the case because there is less resistance, because we are not making waves. But as soon as you start moving this is no longer the case, so it’s more complicated than it seems. »

After analyzing Grousset’s departures, the researcher concluded that in his case, he was more efficient with casts of 12 meters, he who was used to being closer to 14. During the discussion which followed, the swimmer objected that this would force him to perform an additional arm stroke, which would generate additional fatigue and could harm his end of the race in a 100m. “We had agreed, according to his feelings, to do 12 meters by 50m and 14 by 100m,” continues the scientist. And in the end, when he became world vice-champion in the 100m freestyle [à Budapest en 2022]it comes out at 12.”

The same observation was made for Laurent Chardard, double world para-swimming champion, who came to carry out tests at the beginning of January. “This scientific approach is super interesting,” he reports from the Canaries, where he is currently on an internship. It’s not miraculous, the main thing remains the training behind it, but it allows us to really go into detail on very specific points, and if everything is done well that’s what puts you ahead of the game. other in the end. »

In view of the big meeting next summer, the observations made during the last international competitions are rather encouraging. “Causality is difficult to establish, but we have rather gone to the good side than the bad,” estimates Robin Pla, the National Technical Advisor (CTN) in charge of scientific support for the French team. We were more often 3rd than 4th, or more often finalist than close to the final. This is exactly what we are looking for, this shift to the good side. »

Manaudou and Marchand on the bridge

All the work undertaken, whether on casting, the notion of resistance-force (with researchers from Rennes), the energy costs of swimming (with researchers from Rouen) or stroke analysis (with the team of researchers from Lyon), ultimately contribute to inflating these famous marginal gains, the sinews of war in 21st century sport.

Swimmers are generally quite curious about this subject. Florent Manaudou, very fond of data, has already passed through the hands of researchers from the NePTUNE project once and has planned a new visit in the coming months. Announced superstar of the upcoming Olympics, Léon Marchand took advantage of his visit to Rennes during the French championships last June to take some “swimming strengths and resistance” measurements at the M2S laboratory (movement, sport, health), associated with the project.

Beyond preparation for the Olympic Games, this “scientificization” of the approach to swimming must above all be of use to future generations. Because ultimately, between the Covid which locked everyone in from the launch of the program and the year 2021 dedicated to the Tokyo Games, there was not enough time to fulfill all the tasks initially planned in the specifications.

“What is being done at Insep on castings, from a technological point of view, from the use of artificial intelligence, is unique in the world to my knowledge. We have built great tools, but which are difficult to use on a daily basis,” reveals the CTN. In other words, we must simplify the analysis process so that coaches can use it independently, throughout the territory.

Post-Olympic projects have been identified: transferring knowledge, methods and tools to federal leaders and coaches, training technicians, extending tests to young swimmers, relocating video tracking carried out at Insep to others French poles, or even improve the analysis of performance in open water. All this will require money, obviously. The NePTUNE project, which was financed to the tune of 1.56 million euros as part of this PPR, will officially end in November 2024.