In the 19th century, green containing arsenic was a trendy color – the questionable color pigment can also be found on old books. Libraries are now struggling to find the right way to deal with countless suspected cases

Not only artists like Monet and van Gogh relied on the luminosity of this color, toxic green was also popular in book production in the 19th century: But because the so-called “Schweinfurt green” contains arsenic, which is harmful to health, the trendy color of the past is currently putting libraries under pressure to act.

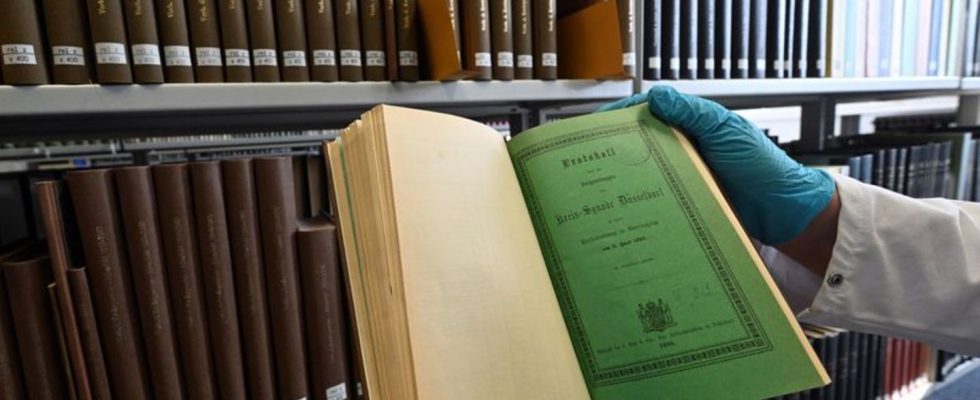

Driven by the requirements of modern occupational safety, archives with historical book collections are currently looking for the correct way to deal with the many potentially contaminated books. Experts advise striking the right balance between risk minimization and caution – but the problem cannot be ignored. And so many libraries face a logistical challenge.

There has been a long-standing technical discussion about potential arsenic contamination

The problem with contaminated books, which had long been discussed in specialist circles, received media attention when the Bielefeld University Library decided at the beginning of February to announce in a press release that, as a precaution, all 60,000 books and magazines from the 19th century would be blocked from borrowing and use. The reason: Arsenic is toxic and carcinogenic – blocking it until it is checked is therefore a necessary precautionary measure.

Other university libraries, including Siegen, Duisburg-Essen, Kiel and Saarbrücken, also announced that they wanted to examine their historical holdings. In order to remove the suspected cases from the shelves for examination, the university library in Düsseldorf closed its doors for several days last week.

No danger if used properly

So reading is life-threatening? The German Library Association (dbv) gives the all-clear in a statement: According to a statement, initial investigations have shown that, when used properly, no higher levels of stress have been found for either users or employees in the libraries.

“Licking a book like this is certainly not a good idea, but nobody does that,” says Reinhard Altenhöner, vice federal chairman of the association. On the other hand, he is convinced that anyone who adheres to clearly communicated “rules of avoiding contact” can work with the historical holdings largely safely.

But the poison in an unknown number of book volumes cannot be explained away; further research is ongoing: stocks and usage scenarios are very different, the dbv continues. How many books from the critical period are in the collection? Are the archives freely accessible or even loanable? It is therefore “the responsibility of every facility to carry out an independent risk assessment and, if necessary, to take appropriate precautions.”

At the end of 2023, the association published a detailed guide on the problem, which was created in collaboration with experts from the Cologne University of Technology and the university libraries in Bonn and Kiel. Tenor: In order to meet the requirements of modern occupational safety, libraries with old holdings must exercise caution, filter out suspected cases as far as possible and determine in individual cases how potentially contaminated books should be dealt with.

“Schweinfurter Grün” brought color into a gray world

“You have to separate and label possible contaminated books. Many libraries are now starting to do this and are addressing this problem,” says Andrea Renate Pataki-Hundt, who worked on the recommendations as a professor at the Institute for Restoration and Conservation Sciences in Cologne. However, the problem is not new to experts.

“I’m surprised that this didn’t reach libraries much sooner,” she says. She has been working with the Bonn University and State Library since 2020 on the question of how arsenic-contaminated volumes can be identified and made usable again – restorers have been aware of the problem with the “Schweinfurt Green” for much longer.

The synthetically produced color pigment was used in the 19th century in wallpaper, ball gowns, wall paints, painting – and in the production of books. The substance and its variations were sold under many names. Because the paint manufacturer Wilhelm Sattler had the dye produced industrially in the northern Bavarian city at the beginning of the 19th century, “Schweinfurt Green” was particularly in demand.

In the rather gray world of that time, in which bright colors were long reserved for the upper class, copper arsenite acetate, which was available to the masses, was an “exciting new color with incredible fascination,” explains Pataki-Hundt. The dye was finally banned in the German Empire towards the end of the 19th century. “The cultural assets from back then remain – we have to deal with them now.”

The experts transferred a test from the water industry that institutions could use to determine contamination of books. It is also important to “detectively track” which route the book took, to carry out appropriate cleaning of the work and storage areas and to also check adjacent books – a lot of work for libraries with large old collections.

State Library: Handle with care

Reinhard Altenhöner also knows this. As the permanent representative of the general director of the Berlin State Library, the dbv vice-chairman also deals with one of the largest book collections from the 19th century that Germany has to offer.

There, too, measures have recently been taken to protect employees and users – but systematic checking for individual cases is not a priority here, explains Altenhöner. The reason is the sheer number of books from the 19th century that the State Library is home to: well over a million volumes come from that time. “That would then reach a gigantic logistical dimension, where you have to ask yourself whether it is worth it in view of the presumed danger.”

It is still completely unclear how many books from that time are actually affected – and how high the burden would actually be in an emergency. “Dealing with this is an ongoing task,” says Altenhöner. However, he doesn’t think panic and excessive measures are advisable: “According to what we know so far, the amounts that appear in the dust or on the book are not high, so we assume that you are not exposed to any danger if certain rules are adhered to,” he says .

Digitization makes it possible to work with loaded volumes

Protective gloves and hand washing are appropriate, and depending on the exposure, mouth and nose protection or protective glasses are also appropriate; in the case of intensive contact, a protective suit can also be useful. Anyone who works with books from the old collections, which are rarely stored in the freely accessible areas of the libraries anyway, must be made aware of how to minimize risks by trained staff.

The State Library is currently thinking about setting up a separate room for the use of potentially contaminated specimens. In many cases, it is now possible to access ancient books with bright green covers without any contact – and therefore without any risk, because large parts of the old collection have long been available digitally: “We should and will now specifically promote this.”