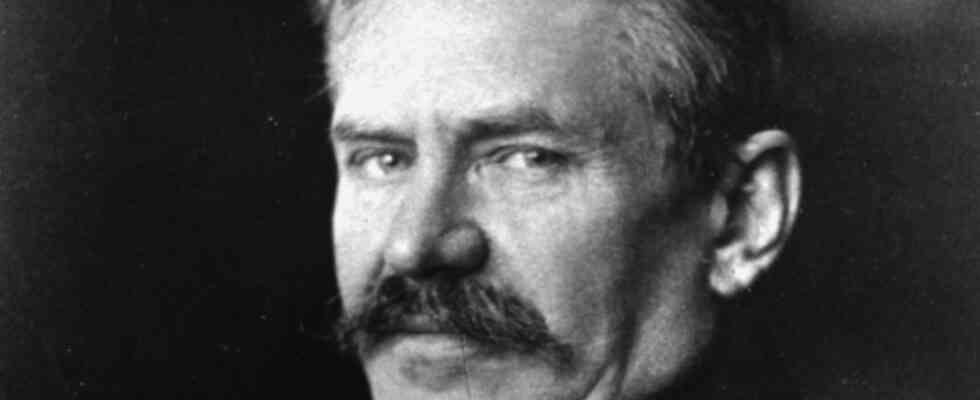

This biography begins with the end. Because no other scene could show the life and character of the liberal theologian, philosopher, publicist and politician Ernst Troeltsch as vividly as his funeral. He died in Berlin on February 1, 1923 at the age of 57 as a result of the flu. Chronic overexertion and despair over Germany also contributed to his early end. Just two days later, a huge crowd of mourners gathered in and in front of the main hall of the Wilmersdorf crematorium.

Famous scholars came, including Albert Einstein, artists and intellectuals, political companions such as Theodor Heuss, not only students but also schoolgirls, which was just as unusual for a Protestant theologian at the time as the many friends with Jewish family histories. The sermon was given by the most important theologian and science politician of the time, Adolf von Harnack. Too many, too long speeches followed, which were broadcast outside because of the rush.

His death in 1923 was a media event, Einstein came to the funeral service, obituaries even appeared in the USA and Great Britain

Over 140 obituaries were published at the same time. The most impressive was written by the last assistant, the later literary critic and essayist Ludwig Marcuse. Troeltsch was even remembered in formerly enemy countries such as Great Britain and the USA. This death was also a media event.

In his great Troeltsch biography, the Munich theologian Friedrich Wilhelm Graf draws this scene with a master’s hand. He sensitively describes the atmosphere and intensively analyzes speeches and articles. He and his team researched surprising details: for example, that Troeltsch’s wife Marta and their nine-year-old son Ernst Eberhard were driven up in Paul von Hindenburg’s car.

Above all, Graf can present the central aspects of his interpretation of life here. Namely, firstly, that Troeltsch – unusual for a scholar at the time – led a life in relationships. Secondly, in the shock of the mourners, as in a mirror, Troeltsch’s enormous vitality, which for many was almost shocking, becomes visible. Because the contrast between the vigorous reader, writer and speaker and his untimely demise could not have been more stark. Third, Troeltsch was one who never finished. Incompleteness was part of his intellectual charisma, now there was a tragedy in it.

Friedrich Wilhelm Graf: Ernst Troeltsch. Theologian in the World Horizon. A biography, CH Beck, Munich 2022, 640 pages, 38 euros.

(Photo: CH Beck)

Specialists have been waiting for Graf’s biography of Troeltsch for a long time. No one else could have written it like that. Graf has devoted his entire professional life to his “hero”. With colleagues, he had collected his far-flung texts, documented them in a 300-page bibliography, and edited them in a 26-volume complete edition that would soon be completed. There were also essays and conference proceedings. When it comes to Troeltsch, nobody has such a good knowledge of the sources and details, can present scientific, political and cultural references in such an illuminating way, and has such an elegant pen as Graf. He also managed to write a biography that is by no means only of interest to experts.

Troeltsch shook the dogmatics of conservative theologians, but also the self-certainty of the progressive camp

Troeltsch is interesting, for example, because one can use his example to discuss whether the Wilhelmine Empire was a reactionary system or an epoch of progress. The way Graf traces his path up to 1914, one has to say: both! Troeltsch grew up and was rooted in a “world of yesterday”: humanistically educated, loyal to the emperor, bourgeois-Protestant. At the same time he was a troublemaker. He shook the dogmatics of conservative theologians, but also the self-certainty of the progressive camp. This made him a leading figure and at the same time an outsider. What he described as his basic conviction in a letter to Harnack in 1900 must have come as a surprise to many: “Christianity has become a new religion in the modern world because it has absorbed completely new content and world views. It is not just a new theology, what we represent, but a new phase of Christianity altogether.”

Friedrich Wilhelm Graf, born in Wuppertal in 1948, is a Protestant theologian and Troeltsch expert. Until 2014 he was Professor of Systematic Theology and Ethics at the University of Munich.

(Photo: Horst Galuschka/Imago)

In the “world village” of Heidelberg he found an ideal place of work and in Marianne and Max Weber inspirational housemates. Here he wrote programmatic essays on the philosophy of religion, on the cultural-scientific opening and consequent historicization of theology, on Protestantism, on sociology. The short texts worked best for him, while he failed in attempts to write the one large book. If you want to get to know him, you should read his book reviews.

As a representative of the university in the Baden state parliament, Troeltsch learned what social and political realities were like. This teaching stood him in good stead when he came to Berlin in 1914 to take up a professorship in philosophy of religion, shortly before the First World War began. As has just been re-lived, outbreaks of war are occasions when public intellectuals sometimes spout over-the-top mischief. From this perspective, too, the biography is extremely interesting. Because Graf shows which paths and detours Troeltsch had to take before he found an ethically clear and politically mature attitude and committed himself to peace and understanding both domestically and abroad. At the same time, Graf does not conceal misjudgments and resentments.

After 1918 Troeltsch intensified his political engagement. He campaigned for the left-liberal German Democratic Party and, as a member of parliament and as parliamentary state secretary, laid the foundations for a democratic order in the relationship between religion and state. As a publicist, he tried, with passion and arguments, to win over the Protestant educated classes, that is, his own class, to the young democracy. Here he waged an increasingly desperate struggle. On the day his friend Rathenau was murdered, he began his lecture with the words: “The enemy is on the right.” Whether one in today’s FDP still knows about this tragic pioneer of a liberal and social democracy in Germany?

It is to the biographer’s credit that he does not forget the “inner man” despite the abundance of scientific and political achievements. Graf also finely describes the difficult aspects of Troeltsch’s personality, but above all he repeatedly addresses his piety. This was – this may seem paradoxical – astonishingly simple, concentrated on what was essential for him: trust in God and love for one’s neighbor. What he wrote about himself as a student in a letter applies to the dying Troeltsch: “Meanwhile I am theoretically a skeptic, practically an ordinary religious person.”