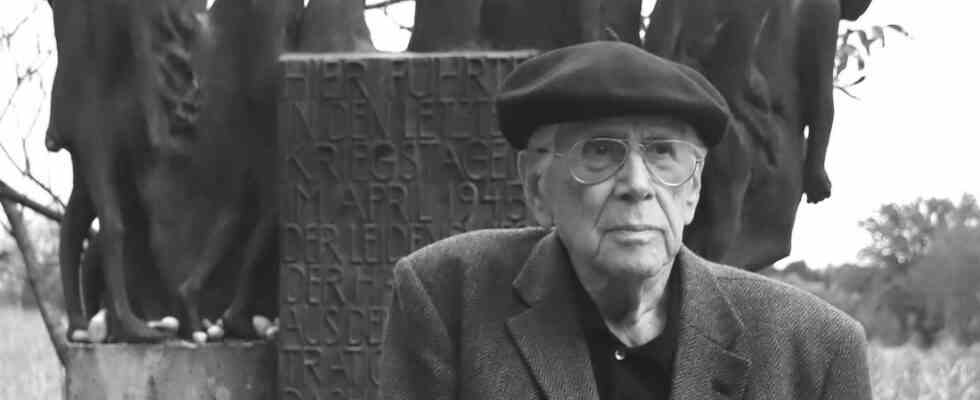

Peter Gardosch had wanted to come to Bruck for the premiere of the film, in which his life and path of suffering is shown. But a week and a half ago, the 92-year-old passed away. His second wife Ramona Gardosch and his son Peter Gardosch spoke in his place at the performance in the cinema, which was attended by more than 100 visitors. “He would have cheered up the audience after the difficult film,” says Ramona Gardosch.

The Gardosch family lived in Neumarkt, Romania, an area annexed by Hungary, Germany’s ally, during World War II. When the Hungarian government begins secret negotiations with the Allies due to the foreseeable defeat, the country is occupied by the Wehrmacht. In May 1944, the Germans began deporting the Jewish population to the death camps.

This also applies to the Gardoschs, who had previously been harassed by the anti-Semitic policies of the Hungarian regime. On June 7, 1944, the train arrived in Auschwitz. Gardosch’s little sister, his mother, and the grandparents were immediately murdered by the Germans. The 13-year-old wears his grandfather’s coat to look older and is spared. Together with his father, Peter Gardosch was deported to Landsberg, where the concentration camp prisoners were supposed to build underground facilities for armaments production. The conditions are murderous, with half the prisoners dying within a few months. Gardosch survives because an SS officer monopolizes him as a servant.

A Benedictine hides the fugitives in the Fürstenfeld monastery

In April 1945, Gardosch had to take part in the death march. The Germans wanted to prevent the advancing US troops from rescuing their victims. When a Wehrmacht truck crashes into the column, Peter Gardosch, his father, two other prisoners and two SS guards take advantage of the confusion and flee. They are hidden in the Fürstenfeld monastery by a Benedictine monk.

It’s a quiet film, a moving document that essentially consists of interviews with Gardosch. Most of the recordings were made during a trip that the director undertook with him to the places of his life, to Neumarkt, Kaufering, Fürstenfeld, Auschwitz, but also to Jerusalem and to the house near Berlin where Gardosch lived. Kronwitter shows how the concentration camp survivor built a new life, first as a journalist in Stalinist Romania. In 1960 he and his first wife emigrated, first to Israel and then to West Germany, where Gardosch accepted an offer from a building contractor to work for him. Gardosch is successful in West Germany, earns a lot of money and is a bon vivant.

But the past doesn’t go away. “There is an infinite sadness in my soul,” says Gardosch in the film. But he cannot talk about the suffering. “He only ever reported on it in small bits,” says his son in Bruck. He kept his fate secret from his second wife Romana for years, fearing that she would not accept him as a German.

Peter Gardosch junior, the son of the deceased, signs the town’s golden book. Right director Max Kronawitter, behind Roswitha Gardosch.

(Photo: Leonhard Simon)

That would have been an aspect that deserved more depth. How did Gardosch stand it in a country where the perpetrators dominated all areas, state, politics and authorities, business, media and science, and the surviving victims were marginalized? The sequence in which Gardosch reproduces a conversation with Albert Speer, the armaments minister, who told him that Hitler had hypnotized the Germans, also remains uncommented.

The dictator may have been charismatic, but that is an outrageous declaration, the justification of a man who made a career. Nazism built on the anti-Semitic and racist ideologies that were consensus in German society, leaned on the middle classes, and was hoisted to power by conservative elites who served as coalition partners. In a photo in the film, Minister of Armament Speer can be seen with an armband and the inscription Organization Todt, the fascist department that was responsible for the construction of the concentration camp near Landsberg.

The film “From Auschwitz to Landsberg, from Jerusalem to Berlin” is available on DVD in the monastery shop in Fürstenfeld.