In “no comedy, no circus” he had “experienced such laughter”, wrote Wilhelm Uhde, the German art historian, writer and art dealer living in Paris, once about the group exhibition “Salon des Indépendants” in the French capital. The jury-free annual exhibition of the “Independents”, which was a counter-event to the traditional and elitist “Paris Salon”, was very popular with the public at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century. The painter Henri Rousseau, born in 1844 and who had never attended an art academy, also presented his latest paintings there almost every year from 1886 until his death.

The pictures look like “a funny accident on the boulevards”

“Rousseau’s pictures are the big attraction,” wrote Uhde, who was a friend of the painter. “Hundreds stand in front of them and laugh. They look like a comic accident on the boulevards that lasts two months; one group replaces the other.” Anyone who praised Rousseau’s pictures at the time would have been declared crazy on the spot. “They would have put you in Charenton if you talked about qualities.” That was of course grossly exaggerated. Uhde, the staunch admirer and supporter of Rousseau, was by no means taken to the Charenton hospital with its closed ward just outside Paris.

Rousseau himself apparently accepted the general amusement about his art with indifference. The autodidact, who was nicknamed “Le Douanier” – “The Customs Officer” in the scene because he worked during the day as a small employee of the Paris customs authorities to earn a modest living, was firmly convinced of his artistic vocation. When the artist died in 1910, there was initially not enough money for a proper burial. Today, of course, his paintings can be found in all the major museums in the world.

For Uhde, the “Douanier”, the “customs officer”, was the leading figure for a whole circle of autodidacts, oddballs and artistic outsiders, to whom he finally presented a thematic group exhibition entitled “Peintres du Coeur-Sacré” in Paris’s Galerie des Quatre in 1928 Chemins lined up. The group of what Uhde called the “five primitive masters” included the elder Rousseau, the gardener André Bauchant (1873 – 1958), the road worker Camille Bombois (1883 – 1970), the housekeeper Séraphine Louis (1864 – 1942) and the postman Louis Vivina (1861 – 1936).

Camille Bombois, son of a bargeman, hired himself out as a farmhand, as a road worker on the construction of the Paris metro and as a porter, worked as a wrestler at the fair and served as a soldier in the First World War. And he painted – for example the “Femme assise sur le puits” (1925).

(Photo: Camille Bombois/Zander Collection © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

From today’s perspective, the framework drawn up by Uhde appears to be a fairly constructed affair. The artists neither knew each other, nor was there a common manifesto or a programmatic aesthetic. All that remains is the petty-bourgeois and proletarian background, which, in addition to being self-taught, was actually common to all. But Uhde, who was himself the son of a Prussian public prosecutor and grandson of a pastor, did not want to see the “low origin” as a link at all.

But because the “outsiders” and the avant-garde of the 20th century were closely related, one can actually speak of the “shadow of the avant-garde” – as the curator and art historian Veit Loers once put it in a nutshell. Rousseau at least may well have felt these underlying pulls, some of which still have an effect today. When Picasso, who was 37 years his junior, organized a party in his studio in 1908, Rousseau made a witty toast that is still repeated today: “We are the two greatest painters of the epoch. You in the Egyptian style and I in the modern style.”

The show is overwhelmingly magnificent and bewildering

With his renewed reference to the “Painters of the Sacred Heart”, the curator Udo Kittelmann is now bringing together numerous paintings by Rousseau, Bauchant, Bombois, Louis and Vivin in an overwhelmingly magnificent, confusing and sensually touching exhibition of paintings that extends over all three floors of the Museum Frieder Burda extends into Baden-Baden. The former director of the Berlin National Gallery celebrates French art from the turn of the century in a joyful, enjoyable, direct and theoretically light-hearted manner.

But it may be a pity that Kittelmann, like Uhde at the time, avoided the class question. Perhaps in the museum that the museum founder Frieder Burda had the New York architect Richard Meier build for him right next to the Staatliche Kunsthalle in the 1990s, there would be a little Marxist-based, contemporary economic discourse and talking about the power of “fine differences” that continues to this day been too attractive in the art business. Ultimately, Kittelmann also wants his exhibition to be understood as a “programmatic and urgent plea” for “snatching artists who do not feel committed to any art trend that is currently dominant in their time from the extensive disregard by the organs of the international art business”.

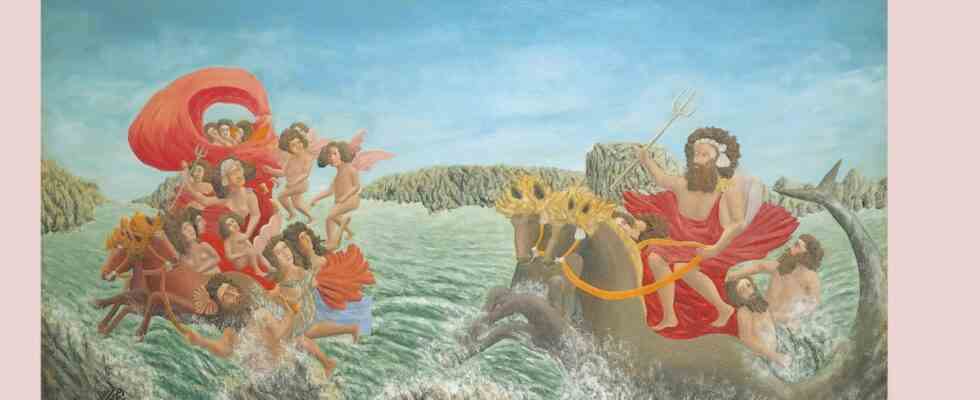

But in the end, the magic and the aesthetic pull of these around hundred-year-old and at the same time timeless-looking pictures, most of which come from the important Cologne-based collection of the gallery owner and patron Charlotte Zander, who died in 2014, were probably too seductive . There are, for example, the incredible paintings of André Bauchant, who was the son of a gardener and a seamstress and later took over the family gardening from his father. As a soldier in the French army, he went to Greece in 1914. From there he returned with an interest in ancient sagas, which is also reflected in his fantastic narrative and event images. “Your work is full of goddesses, heroes and sirens, and also of God,” enthused the architect Le Corbusier in 1949 on the occasion of a Parisian Bauchant exhibition in a letter to the painter, with whom he was a close friend.

Paintings by Camille Bombois were shown at the first Documenta in Kassel in 1955. How might the audience in Kassel in the 1950s have felt in view of the blazing life in pictures like the undated “Nu au collier”?

(Photo: Camille Bombois/Zander Collection © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

Le Corbusier not only owned a whole collection of Bauchant paintings, but was also appointed by the artist as his estate administrator at an early stage. Possibly the architect, who combined photographic Parthenon views with shots of sports limousines in such a way that the machine could be read as a temple and the temple as a machine, appreciated the milky-pastel colors of the antique scenes of Bauchant with the characteristic rock formations because of their modernity. Because he received the decisive boost to art during the First World War, when he completed training as a military draftsman and dealt with surveying technology.

The massive plant pictures by Séraphine Louis, whose active creative phase lasted from around 1915 to 1931, i.e. only sixteen years, have a completely different effect. Dark, shimmering leaves and blossoms inexorably overgrow the surface of her paintings. Louis’ pictorial world draws heavily on Christian iconographic plant symbolism. In 1942, Séraphine Louis, who suffered severely from delusions in her late years, died unnoticed in a psychiatric institution.

Bombois was a farm hand, road worker, porter and wrestler

The fact that the paintings by Séraphine Louis, Louis Vivin and Camille Bombois were shown at the first Documenta in Kassel in 1955 is mentioned in the biographical miniatures in Baden-Baden, but unfortunately not explained in detail. How might audiences in Kassel in the 1950s have felt in view of the full life that Camille Bombois brought to the canvas in the form of landscapes, fairground scenes, portraits and female nudes? Bombois was the son of a bargeman, spent part of his childhood on a barge, worked as a farm hand, worked as a roadhand on the Paris Metro and porter, worked as a wrestler at the fair and served as a soldier in World War I.

From the early twenties he was able to make a living from his art. “Derrière le rideau” – “Behind the curtain” is the name of a picture from 1928 that shows the back views of a dancer and a clown with white make-up and red ears. Both observe their audience through the gap in a curtain. Bombois immortalized the brief moment in which the gaze between the artists and the audience reversed. The painting thus becomes a meditation on contemplation. This art goes far beyond the term “naive”.

The Painters of the Sacred Heart Until November 20th at the Museum Frieder Burda Baden-Baden. The exhibition catalog costs 48 euros.