At the beginning there is still a strange indolence over the pictures. Location on the outskirts of Germany in midsummer, lots of greenery, a social building tower on the horizon, opposite a low-rise building with the Deutsche Bank logo. A radio voice announces that a hostage situation is taking place inside, a lot of police are standing around, the onlookers are at a distance. The camera pans and zooms a little wildly, like TV cameras do when there’s an edit afterwards. However, less is cut here.

The idea of the one and a half hour Netflix documentary Gladbeck by Volker Heise is to show the entire course of that hostage drama from 1988 again, which in its tragedy and drama with the Ruhrpottstadt, where everything began, has become synonymous. But, and that is what is new about this almost excessively documented, filmed and re-enacted crime of the old Federal Republic, only in original recordings. So only with pictures and sounds that were created at that time. Volker Heise is a master of this uncommented collage technique. In this respect, it depends on every snippet that still exists in the archives, zooms and wobbles or pans.

The first effect is that the eye can wander strangely. About the happy pig with the knotted serviette and the blackboard on which “Fresh boiled sausages” are advertised in chalk. It must be right next to the bank branch, officials in helmets and riot gear gather in front of it. You can also enjoy the bright red thong and fresh Mallorcan tan of the undressed policeman who puts the ransom in front of the door. You even learn his name from a recorded radio message: “Richie, take off your clothes!”

When the pack of reporters ganged up: strong feelings of hatred. But it’s her pictures that you’re looking at right now

For those who were of TV-ready age in mid-summer 1988, memories are churning—all of these images were running, in shorter chunks, up and down the main news. But without the serious expressions and the tremolo of the newscasters, which are only shown when important information is missing, the mood is at first provincial farce. The criminals demanded “a 735 BMW” (here a short pause for effect) as a getaway vehicle, also a radio message in the original sound, “but i”. Or TV anchorman Hans Meiser, then RTL, calls the bank branch and asks who it is. “Well, guess who, the bank robber,” is the answer.

Finally, a getaway car that is not a BMW, and certainly not one with an i, starts moving. In the direction of the ultimately well-known, fatal escalation. The police will show incredible amateurism, innocent people will die, 54 hours later everything will come to a bloody and tragic end. Above all, however, reporters and onlookers will exceed all previously known limits of shame: some on the hunt for the most sensational pictures and original sounds, others just because.

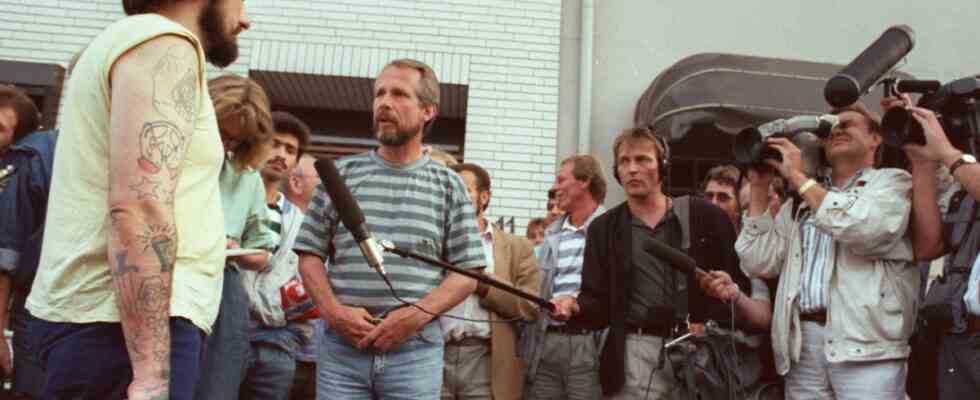

At the latest when the reporter pack first gangs up at a bus stop in Bremen, where you can see the unrestrained sticking up and the camaraderie with the criminals completely uncut, you develop strong feelings of hatred. And at the same time gets caught up in a completely insoluble contradiction.

Because you can now follow the whole drama so minutely up close, because so many reporters shamelessly pointed out at the time. because they ignored all requests from the police for distance and media black-out. because they chased after the hostage-takers, who perhaps wanted to release their hostages in a quiet place, like deranged people. and because all her pictures are still in the archives.

The Dutch police cordon off more space – the recordings immediately become more distant and the tension drops

The most revealing moment comes when the perpetrators cross the border into the Netherlands and they are much better at sealing off the area – immediately the images are from a greater distance, become much worse or are missing entirely. One pays tribute to this Dutch competence – and at the same time is annoyed that as a spectator it is almost impossible that the tension will drop. When the required BMW with i is finally there and it’s back across the border, it’s very, very close to downtown Cologne again.

At that point at the latest you realize that you are only allowed to watch this film if you abstain from any judgment about the other viewers (and filmmakers and interviewers). As soon as you get involved in the matter, you are morally involved. You’re no better than the Cologne gaffers who condemn gazing in front of the camera and then continue looking completely unmoved. The perpetrators almost have to shoot into the air for these early sheep of the dawning always-on age to open an alley for departure at all. And we, in front of the Netflix screen, shouldn’t look down on these onlookers for a second – we are like them.

The realization that apparently nobody is immune to the absurd dynamics of seeing and being seen, of gazing and being the center of attention is perhaps easier today, in the middle of the Instagram and Tiktok age, than it was then. The reporters (audible stage direction: “Hold the gun to your head!”) are of course in no way the same as the perpetrators, who soon devote more time to self-portrayal than to planning their escape. But the victims? When you look at the pictures of Silke Bischoff, who ended up being shot dead by the perpetrators, it gets particularly disturbing.

The hostage-taker Dieter Degowski threatened the hostage Silke Bischoff at the Grundbergsee rest area near Bremen – explicitly for the cameras.

(Photo: Carsten Rehder/dpa)

When she first appears in the footage, she is still one of many faces in the hijacked bus in Bremen. If so, one catches oneself immediately realizing that it is clearly the most photogenic. Could it be a coincidence that the gun is held to her head later in every second picture, that the choice also falls on her when in the end two hostages have to be taken along?

It becomes completely shocking when she also speaks into the television cameras with the gun to her head, surprisingly naturally. As if it were clear that under the magnifying glass of the attention of an entire nation, she also had to say something. How completely carefree and removed from reality she sounds is part of the disruption and destruction of our sense of reality that this collected pictorial material can trigger to this day. They give Volker Heise’s film experiment its clear justification.

Gladbeck: The Hostage Drama, on Netflix.