An Endless Night, Berlin 1931. Unemployment, political violence, nightclubs, prostitution, war injuries, anarchy. Heavy light supps over the streets. In between, empty days in the country, with bathing or clay pigeon shooting. This is what it looks like in “Fabian oder Der Gang vor den Hunde”, Dominik Graf’s latest major work, based on the novel by Erich Kästner, premiered at the Berlinale 2021. “And in all directions there is doom…” The settings come out of the slingshot as quickly as clay pigeons, but don’t take a real end, chop each other off. The pace is so tremendous that the film seems to stagnate.

Dominik Graf celebrates anarchy, spontaneity, lust for the moment and its irretrievability. One would love to sit with him and talk about films and filmmakers – he is passionate about film history – about Murnau and Harlan, Coppola and Klaus Lemke, about Robert Aldrich and Adolf Wohlbrück, Lucio Fulci and Donald Cammell, Jean Eustache and Andrzej Wajda, Morricone and Tarkowski, about the TV series “Homicide”, about Brentano or Schiller, about whom he made films.

Dominik Graf fought for a free, different cinema from an early age, also against the filmmakers of the generation before him who established New German Cinema in the 1960s – Wenders, Schlöndorff, Kluge, Reitz, Herzog (who turned 80 on Monday) – , whose films were quickly too saturated for him: instructional cinema, nerd cinema. The solid support system that they had fought for was to blame for this: “The full subsidization of our industry inevitably makes every director of all stripes the gagged buffoon of the cultural event business.” And grandpa’s cinema was never as dead for him as it was propagated in Oberhausen. Graf was on the side of the underdogs, of Klaus Lemke or Roland Klick, whose films were aggressive, punchy, blurry, dingy. “How dare we actually approach a past with hyper sharpness, as if we knew exactly what it looked like!”

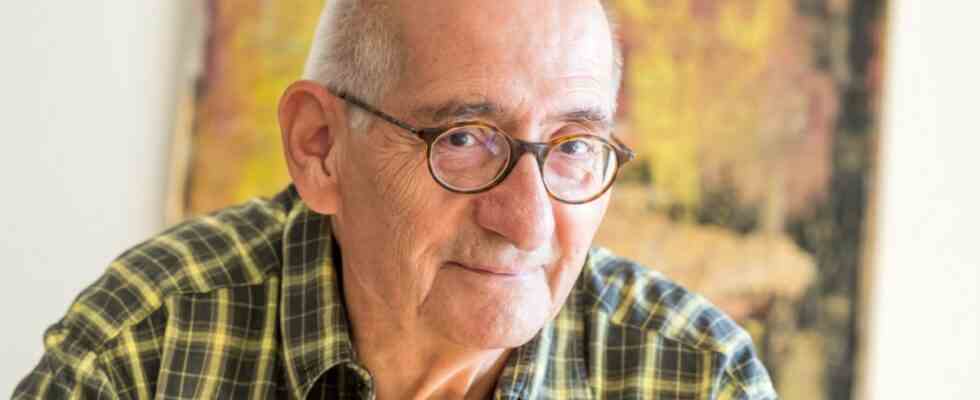

Dominik Graf, Saskia Rosendahl and Tom Schilling on the set during the shooting of the movie “Fabian oder Der Gang vor den Hunde”.

(Photo: Matthias Wehnert/imago images / Future Image)

Dominik Graf was born on September 6, 1952, his parents were the actors Selma Urfer and Robert Graf. In 1974 he began to study at the University of Television and Film in Munich. His graduation film “The Precious Guest” from 1979 received a Bavarian Film Prize. Thus began a career with many surprising turns, some on the brink of catastrophe. The big, multi-million dollar thriller “Die Sieger” was not a hit in the cinemas in 1994, a complex study of a small gang of SEK people who want big money themselves, staged like a passion story, the murderous finale top of the world took place on the Karwendel: the desire to be overwhelmed.

After frustration at the cinema, Dominik Graf kept throwing himself into TV work, he directed contributions to many German crime series, with Schimanski, the “Fahnder”, Sperling, the “Polizeiruf” Chief Inspector Hanns von Meuffels, the Munich “Tatort “-investigators Batic and Leitmayr. “The police series is home and cosmos,” he says. “I myself have never been happier as a director than in those moments when I was allowed to serve supposed ‘crime’ genre ready-made goods and turn the series films onto the streets, into the police offices and at the same time (together with the screenwriter) upside down. “

Graf is the German city filmmaker par excellence, his early films are set in and around Munich (and capture the city’s relaxed atmosphere that blossomed after the Olympic Games), in 2000 he made “Munich – The Secrets of a City”, together with Michael Althen: ” Whether you like it or not,” it says, “everyone carries their own inner city, and like a tree, a cut would reveal age rings that, so to speak, depict how the city is growing in all of us, or the other way around: how to even grows into the city.”

He’s never about the singular work, the masterpiece

The second city in Graf’s work is Berlin, which is connected to Munich by a system of communicating tubes. Munich’s development back to “dwarf” provinciality correlates with Berlin’s urban rise after the fall of the Wall. In 2008 Graf began “In the face of crime”, a ten-part TV chronicle of the city of Berlin reflecting the business of the Russian mafia there, full of emotions and violence, with an explosive production story that then led to the insolvency of the production company. There are no straight paths in this series, they are evasive and devious – and again there is decadent skeet shooting and noble, proud but also heartbreaking love. The first episode begins in a village in Ukraine, a girl dives into a pond because under water you should see the face of the man you will one day love…

Why he feels so at home in the police series: because “the shooting itself is structured a little like the police reality to be told: hierarchically ordered, clear instruction structures, yet an often confusing, overpowering apparatus, often (not always!) annoying, stubborn Superiors, a broken, vain to the core, power-hungry political environment (in our work, this can best be compared with the self-portrayal of the German film industry and the corporate ideology of the TV stations). locations, in the sole service of the cause.”

Dominik Graf is obsessed with filmmaking (and film watching), but he’s never concerned with the singular work, the masterpiece, but rather with a never-ending process that avoids the “event thing”. termite art, is how Manny Farber, the greatest American film and art theorist, put it, the art of the American genre masters Sam Fuller and Don Siegel, Howard Hawks and Raoul Walsh, which “always moves forward and eats up its own limitations and, how not, on theirs leaves nothing but the remnants of their greedy, busy, disorderly activity”. The termite artist Dominik Graf turns seventy on Tuesday.