Books & the Arts

/

June 18, 2024

Peter S. Goodman’s recent book on the pandemic’s effect on global rhythms of supply and demand tries to answer why “the world ran out of everything.”

In the summer of 2022, much of the Indian subcontinent endured a hugely disruptive electricity crisis. In Bangladesh, there were rolling blackouts lasting up to 13 hours a day. Things were similarly bleak in parts of India and Pakistan. In the Indian state of West Bengal, schools were forced to close at the beginning of May, ahead of schedule for the summer break. In Pakistan, one day was cut from the official workweek of public-sector employees.

Books in review

How the World Ran Out of Everything: Inside the Global Supply Chain

Buy this book

All three countries, especially Bangladesh and India, still rely heavily on fossil fuels—gas in the former, coal in the latter—to produce electrical power, and in 2022, all three faced acute fuel deficits. The nub of the crisis across the subcontinent was insufficient power generation, and underlying this were fuel shortages.

The resulting regional electricity crisis was one of many significant manifestations around the world of a much broader phenomenon materializing across 2021 and 2022 as the world slowly reopened following the Covid lockdowns: the snarling of supply chains.

As the normal patterns of supply and demand were upended by the reverberations of the pandemic, the global supply chain—the complex web of economic and logistical connections through which all the world’s products and services are delivered from where they are produced to where they are consumed—struggled, inevitably, to cope. Fuel for electricity production was far from the only commodity affected: Toilet paper, face masks, and cars were just some of the many products in which significant disturbances of delivery occurred.

Peter S. Goodman labels this historic phenomenon the “Great Supply Chain Disruption,” and it’s the focus of his new book, How the World Ran Out of Everything. Currently the global economics correspondent for The New York Times, Goodman is a longtime economics reporter whose previous books include 2022’s Davos Man, a coruscating takedown of internaional elites, the title referring to the men who gather each year in Switzerland for the World Economic Forum.

Goodman’s strategy in How the World Ran Out of Everything is to invite the reader to accompany him as he explores the various key links in what are often long and convoluted supply chains connecting the world’s producers to its consumers. Along the way, he meets a wide array of people whose livelihoods are bound up with keeping the products flowing.

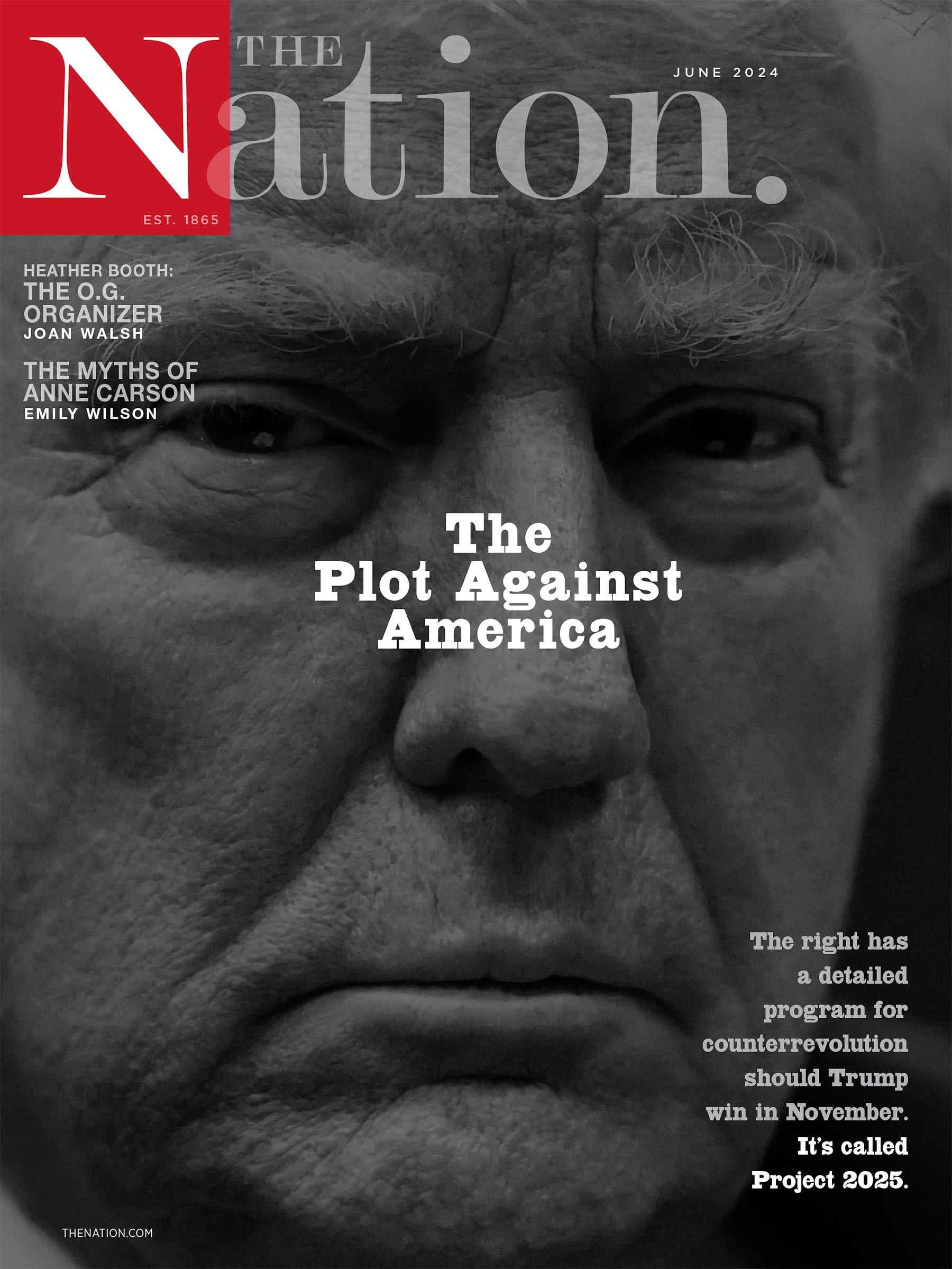

Current Issue

Yet while Goodman hints (not least in the book’s title) at generalized and large-scale product shortages, he never really substantiates their existence. Rather, what he does substantiate is more revealing: supply-chain disruptions for certain goods, in certain places, and impacting certain economic actors.

The core sites of interest in Goodman’s account are the main transportation sectors that together make up the global supply chain for all but the highest-value, smallest-volume, most time-sensitive products (which are typically flown by air). Hence trucking, rail transportation, and, above all, ocean shipping are the economic milieus that Goodman investigates and attempts to bring to life, explaining for his readers how they handled (or, alternatively, did not handle) the convulsions of the pandemic era.

Goodman’s research leads him to make three main points about the modern global supply chain. The first is that the world had been left singularly vulnerable to supply disruptions because of the so-called “Just in Time” business revolution of the post-1970s. Egged on by efficiency-obsessed consultants (McKinsey and the like), multinational firms cut all the “fat” from their business operations, in particular the storage of spare inventory and backup parts, and instead relied on their supply chains to deliver the right number of components in exactly the right place and moment—i.e., just in time—to enable efficient, “lean” production. Companies such as IBM and Toyota became famous for their enthusiastic adoption of Just in Time principles. Of course, such a method doesn’t leave much room for error even in the most normal of times, and the period from 2021 to 2022 was very far from normal.

The disruptions of those years, however, were not just about an inherently fragile global production system failing to weather unpredictable and volatile rhythms of supply and demand. Profiteering by unscrupulous actors at the heart of the supply chain evidently served to exacerbate these disruptions. For example, the huge ocean carriers that ship goods around the world on vast container vessels directed their scarce resources to where the available profits were greatest, which was not necessarily where there was the greatest need for those resources. This is Goodman’s second principal point.

Third and finally, Goodman finds massive inequalities between corporate executives and ordinary workers all along the supply chain. These inequalities did not just surface in the midst of the Great Supply Chain Disruption; they were already there, part and parcel of what he calls “the conditions on which normalcy rested.” In other words, “a functioning supply chain has come to depend on routine forms of exploitation.”

“It took,” Goodman maintains, “a rare event—literally a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic—to render these truths undeniable.” Yet to those who had been paying attention, the basic way that capitalism works—the exploitation endemic to it, including in transportation businesses—was already undeniable long before a novel coronavirus emerged in late 2019.

This does, however, raise an interesting and important question: Why was it only now that US-based commentators came to see things for what they are? What was it about the Great Supply Chain Disruption of 2021–22 that caused people to finally sit up and take notice?

The answer surely is that for the first time in a long time, American firms and households were (sometimes) being inconvenienced and losing out. Reports about global supply lines being overwhelmed invoked the threat specifically to American consumers. Indeed, the purported travails of the latter—“record shortages of many products that American consumers are used to having readily available”—were repeatedly cited as evidence for “supply-chain bottlenecks…around the world.”

That a global supply chain—organized largely by and for profit-seeking firms—inevitably produces both winners and losers has always been self-evident to those on the losing side. Supply chain disruptions have never been anything but a normal part of life for suppliers and consumers in poor countries, long reconciled to not necessarily being able to sell or buy what they need to, or at least not at an affordable price.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

American producers and consumers are accustomed to winning. Disruptions of the kind that occurred in 2021–22 don’t ordinarily happen to them. That they did now was what was unusual, and what rendered certain truths suddenly seeable.

It is far from coincidental that the main sympathetic protagonists of How the World Ran Out of Everything, to whom Goodman repeatedly returns to tell his story, are two small US firms.

One is a Mississippi-based company that sells small plastic toys, which in 2021 encountered enormous difficulties in transporting those toys affordably from China, where they are manufactured, to the United States, where they are bought and sold. The other is an almond-farming operation in California, which was having no less difficulty with the reverse challenge—getting its products affordably out of the US, to customers in the Middle East and Japan.

It is by investigating these specific supply chain challenges and the transportation gatekeepers standing obstinately in his protagonists’ way—first and foremost, the above mentioned ocean carriers—that Goodman discovers what had been hiding in plain sight: that, as Matthew C. Klein and Michael Pettis have put it, “trade wars are class wars,” and the people who lose out in them are US workers as well as those laboring overseas.

Not surprisingly, the plight of US workers is the focus of Goodman’s chronicle. “Keeping store shelves stocked,” he laments, “has in recent decades demanded that truck drivers miss their wedding anniversaries. Maintaining the flow of cargo has required that rail workers remain on the road for weeks at a time, even when their children need surgery.” And so on.

If there is anything substantial to quibble with in Goodman’s belated telling of the class dimensions of globalization in general, and of China-US trade in particular, it is his narrow roll call of who the winners have been. Newly convinced of the villainy of Big US Capital, Goodman surmises that it is only American corporations and executives that benefited from China’s becoming factory floor to the world. “Chinese factory workers,” he writes, “were getting cheated by bosses who themselves were getting squeezed,” as “the primary beneficiaries of China’s export boom sat in the United States itself.”

Which, needless to say, is not exactly true. Certainly, the capitalist class in the United States benefited. But so too, and probably to a greater extent, did Chinese business elites. After all, from the early 2000s on, the number of billionaires in China grew exponentially; by the mid-2010s, it had even overtaken the number of US billionaires, and the gap was widening. But as it happens, ordinary Chinese workers were not faring as badly as has been commonly supposed: In the 2010s, their manufacturing wages grew at rates far faster than elsewhere in Asia.

Of course, it can’t be denied that US producers and consumers clearly did experience supply chain seizures in 2021 and 2022. Still the impact was relatively modest, and the United States was, in fact, far less devastated than much of the rest of the world, despite a high volume of disruptions. One wouldn’t know that from reading Goodman’s book.

Disruptions in the United States and other rich countries tended, for the most part, to be short-lived and isolated to specific product lines, and they represented, with few exceptions, relatively minor inconveniences. In reality, the richest corners of the world did not run out of much of anything. Panic buying proved almost completely unnecessary more or less everywhere it occurred, and when the product shortages that concerned so many people did materialize, they were generally not the precursors to panic buying so much as resulting from it.

Indeed, one could argue that a book called Why the World Did Not Run Out of Everything would prove to be much more revealing. Given the savage, unprecedented shock that the pandemic brought to bear, one might reasonably have expected to see more shortages of more products, in more places, and for much longer periods. Even though it proved largely unnecessary, panic buying was, at the time, wholly explicable: Many people feared a kind of generalized breakdown, and understandably so. It seems to me in hindsight that the relative success of the global supply chain in withstanding these challenges is what demands explanation.

In an article published in late 2021, the Financial Times columnist Tim Harford captured the rather banal reality of Goodman’s Great Supply Chain Disruption, at least for the wealthiest parts of the globe. Harford recalled how, in early 2020, “as Covid-19 spooked shoppers,” he had consulted a prominent supply chain expert, MIT’s Yossi Sheffi. Sheffi, Hartford writes, had been “relaxed,” reassuring him, “We are not going to run out of food.” Any problems, at least in rich countries, were likely to be brief and relatively trivial. In hindsight, Harford concludes that Sheffi had been right to be sanguine, remarking: “We did not run out of food. We ran out of kettlebells. And civilisations do not collapse because of a shortage of kettlebells.”

No, indeed, they do not. But civilizations might just collapse because of a shortage of energy. Which takes us back to where we started, with South Asia and its electricity crisis.

The blackouts that affected large parts of South Asia in the summer of 2022 were not only hugely disruptive; they were also deadly. Sometimes occurring during the evening hours, the cuts disturbed sleep cycles and left people increasingly fatigued. As resistance to heat stress was sapped, hospitalizations and deaths from heatstroke soared.

Blackouts were something that many people in 2022 thought were coming to Europe, too. Though the power grids throughout Europe are less reliant on fossil fuels than, say, in India or Bangladesh, gas and coal remain a crucial part of the supply mix. And Europe’s supplies of gas, in particular, were thrown into disarray from the beginning of 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine. Russia had been the biggest supplier of gas to the European Union; both sides now sought to reduce supply volumes drastically. Combined with a shortfall of nuclear generating capacity and a drought-induced impairment of hydropower, this sudden loss of gas supplies was the source of the fear that the lights might go out come wintertime.

But it didn’t happen. The lights stayed on in Europe.

How so? Far and away the most important factor was that the EU successfully scrambled to secure the gas it needed by switching from Russia to alternative suppliers. Here’s the catch: Those alternative supplies, secured via powerful energy traders such as Eni SpA and the Gunvor Group, were ones that other countries had been relying upon to keep their lights on. And the main countries to lose out in this way were precisely the South Asian countries in question: Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. The story is a complex one, but basically those poorer countries were outbid. The currency of markets (no matter the commodity) is cold, hard cash, and buyers in the EU had more of it.

The point of the story is simply this: The supply chain disruptions of 2021–22 were experienced to massively different degrees in different parts of the world, and how one country experienced them was closely interconnected to—shaped by, and shaping in its turn—how other countries did. Of this complex, variegated, and deeply uneven international intertwining of resource endowments and institutional capacities, How the World Ran Out of Everything makes all too little mention. The world, it must be stressed, did not run out of anything.

To be sure, Western countries like the United States and the wealthiest nations of Europe were affected, which came as a nasty surprise. But in terms of the wider ledger of the global supply chain and the shocks that it periodically experiences and dishes out, the West is clearly still very much winning.

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish every day at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Neighbors and Other Stories, a posthumously released collection, looks at all the uncertainty and promise of coming of age during and after the civil rights era.

Books & the Arts

/

Kelton Ellis

Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s new film, an eco-thriller set in a sylvan Japanese town, explores the messy entanglements of human, machine, and nature that make up planetary existence.

Books & the Arts

/

Phoebe Chen

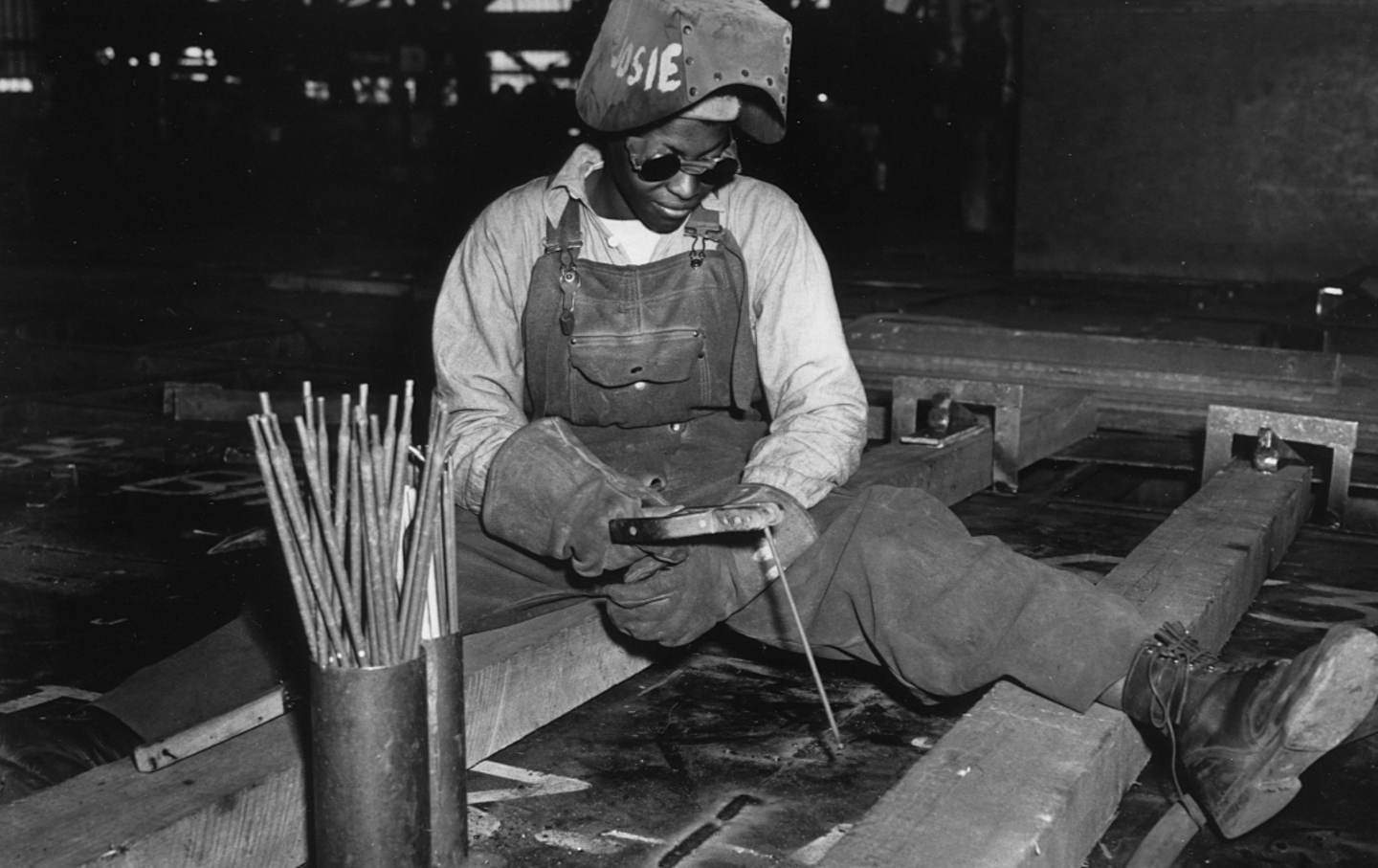

By focusing on the Black working class and its long history, Blair LM Kelley’s book, Black Folk, helps tell the larger story of American democracy over the past two and a half cen…

Books & the Arts

/

Robert Greene II

Ann Powers’s deeply personal biography of Joni Mitchell looks at how a generation of listeners came to identify with the folk singer’s intimate songs.

Books & the Arts

/

David Hajdu