On October 26 and 27 in a courtroom in Burkina Faso’s capital, Iboudo was the prosecution’s first witness. Ahead of him, steps ascended to the red-robed judge, the military jurors, and the state prosecutors, and behind him were lines of black-robed lawyers and an audience that stretched out to the edges of the wood-paneled room. Ilboudo wore a gray shirt and loose-fitting slacks. From my seat, all I could see was the back of his shaved head as he was questioned about what he did on October 15, 1987.

“Present!” Ilboudo snapped like a soldier during a drill, each time his name was announced.

Iboudo claimed that he drove four armed men to the government building where Sankara was gunned down. He heard the shots but didn’t see who fired them. When asked if he saw Gen. Gilbert Diendéré, a senior military official at the time, he faltered and often said it was “complicated” or difficult to remember. The audience laughed at his baffled manner and short responses.

Chrysogone Zougmoré, the president of the Burkinabé Movement for Human Rights, which has documented hundreds of extrajudicial killings committed by Burkina Faso’s military during counterterrorism operations, said the trial is a “victory” that could pave the way for greater accountability within the security forces. “The military are now answerable to the law like everyone else,” he told me. For the Sankara family’s longtime lawyer Prosper Farama, the trial will send a message that those who stage coups will be punished. “Through this Africans will understand that a coup d’état is not a way to come to power,” he said.

And for two female law students, Marie-Louise and Zenabo, who sat at the back of the courtroom and are too young to remember Sankara alive, more was at stake. Marie said she saw the trial as a test of whether there could be “justice in Africa,” and Zenabo said it was about seeing if there could ever be “impartial judgement” in Burkina Faso.

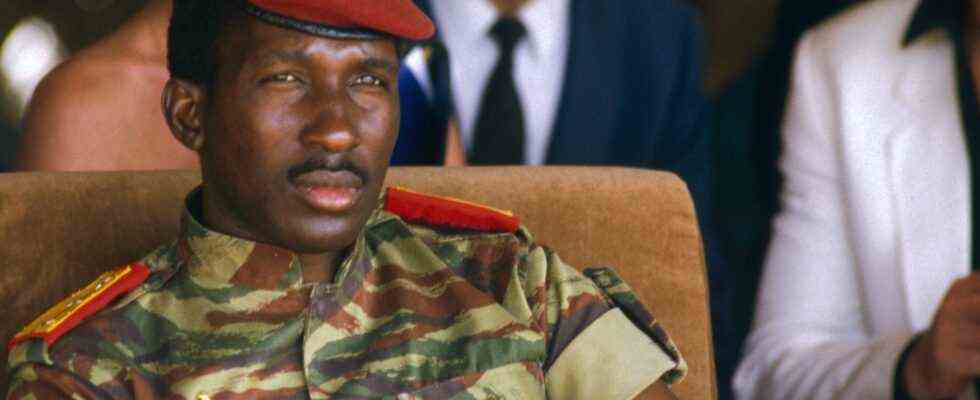

For more than three decades, Sankara’s death has remained an open wound in the former French colony. The story of his assassination has all the elements of a modern tragedy: Two soldiers and close friends, Sankara and Blaise Compaoré, seize power together in their early 30s, with Sankara becoming president and creating collectivist policies to make the nation self-sufficient. Sankara even renamed the country Burkina Faso, which draws from two native languages and means “the land of upright men” or “men of integrity.” But tensions between Compaoré and Sankara began to rise over leadership and the direction of the revolution. Then a group of assassins gunned down Sankara and his colleagues outside a government building. Suspicions of French and foreign involvement remain, which Burkina Faso is investigating.

After Sankara’s death, the US Embassy supported Compaoré, who was considered more open to French and US neoliberal policies during the Regan administration, according to Brian J. Peterson, a history professor at Union College who recently published a biography on Sankara. Peterson read through thousands of US diplomatic cables and reports, and confirmed that the Americans in Ouagadougou had considered a coup likely and maintained a network of informants within the military and government. (The US government has never publicly commented on Sankara’s assassination, and a spokesperson for the US Embassy said, “The United States recognizes the importance of the trial to resolve questions and bring justice in this long-standing case, to reenforce the role of the judiciary, and as part of the country’s ongoing efforts at national reconciliation.”)

Sankara’s murder four years into his presidency, when he was 37, was followed by 27 years of Compaoré rule before he was overthrown in a popular uprising in 2014, during which Sankara’s image and his pro-poor and anti-colonial policies became a rallying point for demonstrators. Seven years later, as the country faces rising terrorist attacks from groups affiliated with Islamic State and Al Qaeda, some question the trial’s relevance. Among them is Paul Kéré, one of Diendéré’s defense lawyers, who told me, “In view of the urgency and the insecurity, it is not an ideal time hold this trial, since it necessitated the mobilization of a lot of money, which could help to fight against the insecurity.”

Both the alleged mastermind and the lead executioner in Sankara’s assassination—Compaoré, who lives in lavish exile in neighboring Ivory Coast, where he holds citizenship; and Hyacinthe Kafando, a commando who allegedly led the killings and remains at large—will not be present for the trial. (Compaoré and his lawyers have rejected the legitimacy of the process). Burkina Faso sent out an international arrest warrant for Compaoré in 2015; months later, he was granted Ivorian citizenship. The Ivorian government has not publicly commented on the warrant.

But without the testimonies of these men, lawyers for the Sankara family are afraid the story of what really happened that day will remain incomplete. “The whole truth won’t be told,” said Ferdinand Nzepa, an attorney based in Toulouse, France, who is one of the seven lawyers representing the Sankara family. “We are disappointed, because Kafando is not here; we are very disappointed that Blaise Compaoré is not here, because it is an opportunity for him to tell his truth. He is the central person in the trial.”

Nzepa is worried that only the “pawns” will be punished. But after a quarter-century of fighting alongside Burkinabè lawyers to have the case heard, Nzepa said he welcomes the trial, however imperfectly it unfolds. His colleague Ante Guissé, a Paris-based lawyer, who often defends those accused of war crimes at international tribunals, said the case will help set the record straight on the “inaccuracies” in the way Compaoré and his regime portrayed Sankara.

“Sankara was depicted as a bad guy who wanted to stage a countercoup,” Guissé told me. “It is important for the family to have the truth—that was never the case; he knew that his life was threatened, and he didn’t make any moves because he didn’t want to cause bloodshed.”

Every morning, a military convoy roars through the main streets of Ouagadougou, transporting the accused to the court. Outside the proceedings, armed soldiers sit behind machine guns mounted on pickups. Inside the courtroom, gargantuan air conditioners huff from all corners, and the lights studding the wooden ceilings flicker above rows of chairs. Mariam, Sankara’s widow, who lives in France where she fled with her two sons, quietly listens, her face half covered by a black Covid-19 mask. Sankara’s two younger brothers, Valentin and Paul, are there every day.

All of the accused have been provisionally released, except for Gilbert Diendéré, who headed a specialized elite unit during Compaoré’s regime called the Regiment of Presidential Security and was previously sentenced to 20 years in prison for attempting to stage a coup after Compaoré’s ouster in 2014. Sankara’s lawyers have expressed concern for witness safety and protection. Almost half of the accused who are present have lawyers appointed by the state, and often show up to court in the same shirts throughout the week. The higher-ranking soldiers, among them a military doctor, who wrote death certificates saying Sankara died of “natural causes,” and a former head of the gendarmerie, accused of destroying evidence from a wiretapping machine with French agents, have their own lawyers. Diendéré himself has a team of at least four.

Since the accused are all current or retired soldiers, the court is a hybrid civilian and military court, with two civilian judges and five military jurors. Military prosecutors and lawyers for the families of the victims and the accused have been poring over 20,000 pages of evidence and days of testimony in a trial that is expected to last four months. Many of the documents include long interviews before a judge of inquiry, who in Burkina Faso’s French-styled legal system conducts private investigatory hearings to determine if there is enough evidence to prosecute a case. These interviews are concealed from the public and only referred to in the trial proceedings.

In court, Ilboudo claimed to have forgotten what had been said in much of his testimony before the judge of inquiry, but there were parts of his story that remained consistent, such as the journey to the Conseil de l’Entente, the government building where Sankara was shot dead.

Ilboudo said he was waiting outside of of Compaoré’s house, when Hyacinth Kafando, one of Compaoré’s notorious security aides, ordered him to get into a car with three other armed men.

“Start the car and follow Maïga,” Kafando told him, referring to another of Compaoré’s drivers and bodyguards, who drove two other armed men.

“Where are we going?” Ilboudo said he asked Kafando.

“Just follow Maïga. Do not try to know what you shouldn’t know,” Kafando responded, according to Ilboudo.

“When you arrived at the Conseil, what happened?” the judge asked.

Ilboudo said he drove to a building where Compaoré is believed to have sometimes stayed. Kafando briefly went into an apartment before getting back into the car.

“Hyacinthe [Kafando] told me to accelerate and go overtake Maiga. He took my hand, and he directed the wheel,” he said. Then they crashed into the wall of a nearby building where Sankara was holding a meeting. The radiator was pierced, and the car came to a standstill, he claimed.

According to Ilboudo’s testimony, he was an unknowing participant who didn’t see much when guns started firing. But he recalled that there were eight men in the two cars, all of them armed. Sankara walked out of the building wearing a sports uniform and with his hands in the air. Ilboudo said Kafando fired first, but he wasn’t sure who shot Sankara. He said he saw four bodies on the ground and that he never left the car during the four or five minutes of gunfire. He said his AK-47 was missing when it all started, and then it appeared when he returned to Compaoré’s home.

Compaoré’s bodyguards always traveled with arms in the cars—a rocket-propelled grenade launcher and a machine gun with 120 rounds—he said under questioning by the civil party lawyers representing Sankara’s family.

Ilboudo’s state-appointed lawyer, Eliane Marie Natacha Kabore, posed straightforward questions to her client: “Did you shoot Thomas Sankara?” (“No,” Iboudo responded firmly.) “Did you help Blaise Compaoré stage a coup d’état?” (“No.”)

Claiming that he was mentally ill, she changed his plea to not guilty, saying he didn’t understand what he was doing when he pleaded guilty.

When asked to confirm if he saw Diendéré there, Ilboudo said it was difficult to remember. One of the civil counsel lawyers cited Ilboudo’s hesitance to speak as a sign of fear and asked whether he was being intimidated: “I’m afraid,” Ilboudo said, but he didn’t go into specifics. The judge offered him state protection, and pressed him on the veracity of his statement for the judge of inquiry. Ilboudo confirmed that what he said was true: Diendéré had been there.

Thirteen days after Iboudo took the stand, Diendéré, the trial’s most anticipated witness, stood in the dock, a towering figure in the green leopard-print military uniform of the much-feared Régiment de sécurité présidentielle, a specialized unit that received US funding and training and was disbanded after the fall of Compaoré’s regime. Diendéré said he wore the uniform as a homage to both Compaoré and Sankara who dressed in it during the revolution. Prosecutors initially accused Diendéré of assassinating Sankara and interfering with witnesses, but his charges were changed to “complicity” in the assassination, concealment of corpses, and attacking state security. Diendéré denied the accusations.

For two and a half days, Diendéré, now in his early 60s, gestured with sweeping arms, turning to face the prosecutor often and sometimes the audience. Soft-spoken, he responded matter-of-factly and occasionally made jokes as he discussed his role and the chain of command at the time.

Why did he hold a meeting at the Conseil d’Entente earlier that morning? (A: To quell rising tensions between Sankara and Compaoré’s camps.)

Where was he when Sankara was shot? (A: On the other side of the wall from Sankara—unarmed and in sports gear, as Sankara had mandated that all government workers exercise on Thursday afternoons.)

Diendéré said he heard the shots, rushed to the scene, and saw Sankara’s body and those of the others. He did not know what was going on, and because he was unarmed, he said, there was little he could do. He called Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani, his senior commander who was later executed for allegedly attempting a coup against Compaoré. Diendéré said he didn’t remove the bodies, but someone took them away in the evening. During this time, he said Compaoré was bedridden at home.

Outside the Conseil d’Entente, a bronze statue of Sankara stands with its fist in the air. On its concrete base are bronze plaques of the faces of the 12 others who were killed there. Sankara’s speeches play from a nearby speaker. The site is a tourist attraction for locals and the foreigners who visit despite the insecurity. There is an upturned heart-shaped wreath of fake flowers that sits near an entrance with a large portrait of Sankara wearing a red beret and smiling. The flag of Burkina Faso hangs above it.

Compaoré’s old house, where Ilboudo alleges they set off from, sits behind rolling blue iron gates, and is less than a kilometer away on Independence Avenue, a thoroughfare lined by government buildings. The home is next door to a burned-out assembly building that protesters torched during the overthrow of Compaoré’s regime. The French Embassy is a few buildings down, behind yellow blast walls. The Conseil de l’Entente is just a few minutes’ drive away. If Ilboudo’s account of what happened that day is true, would he have had time to stop the car or turn back? As a private, could he have made that call?

Roger Bayi now guides the tourists who come to see the memorial. Bayi, whom Sankara sent to study in Cuba as a high school student to gain technical expertise, saw the revolutionary as a father figure. But he never made use of his training in hydrothermal energy and sees Compaoré’s regime as having robbed him and the country of a better future. Still, he is optimistic about the trial. He told me, “Even if the accused lie, the truth will come out.”

Oumarou Kombere contributed reporting.