In early April 1994, when the genocide began in Rwanda, the meetings started in Washington. “They couldn’t say we were not going to do anything, because that’s bad policy,” recalled Prudence Bushnell, then the deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs. “So we were tasked to meet every single day in secured video conferencing, lest we be seen as doing nothing.” The United States, still smarting from the casualties in a peacekeeping operation in Somalia depicted in Black Hawk Down, had no intention of spilling more American blood on African soil. But Bushnell latched onto an idea, circulating among activists at the time, that she believed could stop the violence: jamming Rwanda’s airwaves.

It was meant to be a meaningful half-measure at a time when the most powerful officials on those video conferences were committed to taking no measures at all. It would end up haunting US foreign policy—and distorting how we understand ethnic violence—for decades to come.

A tiny country that had just recently become a democracy, Rwanda had two major radio stations, and one of them—founded by the leaders of an extremist, ethnocentric political party—broadcast vitriol against Tutsis, the country’s minority population. Its presenters stoked fear in listeners already on edge from years of civil war and called Tutsis “the enemy,” often describing them as “cockroaches.” As the mass murder spread, the station encouraged people to join in, sometimes naming individual Tutsis who had escaped the violence and Hutus who opposed it, urging its audience to hunt them down.

Human rights activists in Washington lobbied hard on the unique power of radio in Africa to do harm, but Bushnell believed it could also do good. Just weeks before the genocide began, she’d been in Burundi, where there was sporadic violence between the same ethnic groups. Officials at the US Embassy told her the fighting often subsided when important foreigners were in town, so they put her on the radio. “The next day, a woman came up to me and said, ‘Thank you for what you said. Because you were on the radio, no one was killed last night,’” Bushnell told me. “That’s why I thought I could stop a genocide. Can you imagine?”

Today, Bushnell thinks she was naive, but in 1994, she said, she pushed her colleagues to use a military aircraft to broadcast signals that would jam Rwanda’s radio frequencies. Her colleagues pushed back: The lawyers said interfering with radio frequencies was illegal; the Pentagon said Rwanda’s hills would weaken the jamming signal, making it an uncertain tool at best, and that the price tag was too high—the only aircraft capable of doing the work cost $8,500 an hour. Finally, Bushnell said, a senior defense official put it plainly: “Radios don’t kill people. People kill people.”

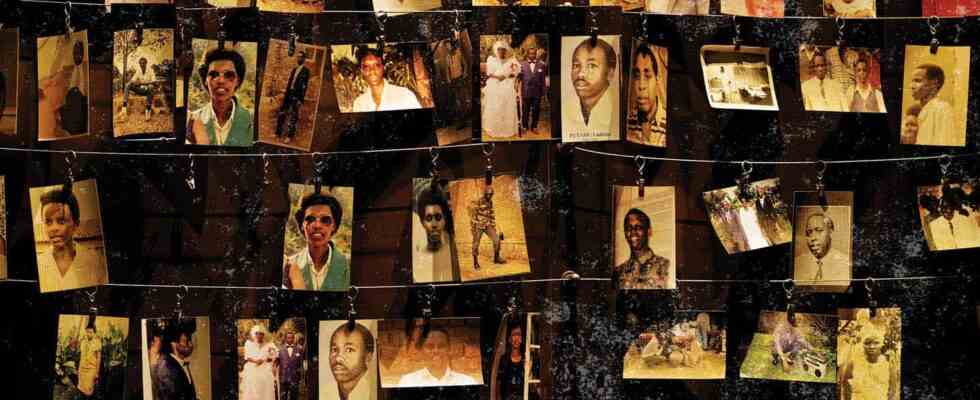

In the end, the US took no action to slow or stop the genocide, engaging in semantic gymnastics to avoid even using the word out of fear it would trigger a legal obligation to intervene. More than 800,000 people died in what became known as the Genocide Against the Tutsi. It ended only when a Tutsi rebel group led by the country’s current president, Paul Kagame, won the civil war.

Refusing to jam the frequency for Rwanda’s “machete radio,” as an international tribunal later called it, has become a symbol of US indifference to genocide. As a story, it appeals for its irony: the enormity of the violence, the simplicity of the solution. But as a genocide-prevention strategy, stopping radio broadcasts was always a fantasy—one that the American imagination clings to because it affirms a foundational myth of US power: The white world runs on politics, and everyone else is a mob away from “tribal violence.”

“For those of us who didn’t know about Rwanda, [there was] this idea they listen to a radio and then go out and grab a machete or a rock or a spear,” said Scott Straus, a professor of political science at the University of California, Berkeley. “Jamming the radio might have delayed the violence, but it wouldn’t have changed the outcome.”

Straus interviewed more than 200 of Rwanda’s convicted genocidaires and found that, while most of them knew about or listened to the infamous broadcasts, hate radio was not the reason they joined the killing. Rather, they said, men with power or authority had recruited them face-to-face, and they participated because they were afraid—of both the rebel group with whom Rwanda had been at war for four years and their own leaders, who they suspected might brutally punish them for refusing to participate. “They were making calculated choices about survival and how best to protect themselves and their families,” Straus told me.

Data suggests that where genocide has occurred, political elites—those with the power to turn genocide from possibility into policy—made similar calculations, under similar circumstances. Benjamin Valentino, a professor of government at Dartmouth and a founder of the Early Warning Project at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, has found that genocide has a clear, if perverse, logic: Often, genocidal regimes begin with rulers who feel at risk of losing power, usually to a minority group and often one already engaged in armed rebellion or insurgency, and eventually decide that genocide is their best, and sometimes only, path to survival—political, cultural, existential. “Once we understand the goals and interests of the people in power, we can see them reasoning toward that radical solution,” Valentino said. “Without that decision, you may get low-level violence, and you’ll almost certainly get repression, discrimination, and exclusion—but you won’t get genocide.” That is, genocide is a policy choice, not an explosion of negative passion.

Yet hatred remains a powerful causal hypothesis. Uncomplicated by context, hatred feels as visceral and impulsive as the violence itself. Enmity is also easy for outsiders to recognize and understand, even if they don’t know much about the local dynamics. In 1994, the Western media settled easily into a script about ancient hatreds, upsetting actual Rwandans with access to foreigners’ narratives about their home and history. “I am profoundly offended by…news reports describing what is being perpetuated in Rwanda as some mindless ‘ethnic slaughter and tribal violence,’ instead of the politically motivated, long-planned systematic mass extermination of an entire people by those Presidential Guards and the death squads acting under their orders,” wrote Louise Mushikiwabo, a Rwandan living in Washington, D.C., whose brother had been among the first to be murdered, in a letter to The Washington Post published in 1994. (Mushikiwabo later became Rwanda’s minister of foreign affairs.)

Journalists weren’t the only ones to describe the violence as if it were a grassroots reflex that happened to find tacit government approval. US State Department memos recounted historical massacres of Tutsis, as if the country’s past necessarily mirrored its future. In one of her regular telephone calls to a top Rwandan military official, later called the “mastermind” of the genocide, Bushnell warned that he and his soldiers would be seen as “complicit” for “aiding and abetting civilian massacres”—massacres that were, in fact, planned and coordinated by the military itself. American activists, meanwhile, insisted that hate radio was delivering orders—they rarely specified from whom—as if to a willing audience of automatons.

None of this is to deny the importance of radio to Rwanda’s genocidaires. Straus found that extremist broadcasts did influence the most violent perpetrators. Even if radio didn’t catalyze the masses or ignite the genocide, he identified occasions when the broadcasts helped elites to coordinate their campaign of killing. Hate propaganda can normalize the dehumanization that is often observed in societies where genocide occurs, and it can make violence seem more “natural” once it begins.

But normalizing violence, despicable as that is, is not the same as causing it. As Valentino told me, “You can’t just observe that hate speech is common in society and assume that that society is more likely to have a genocide.” Valentino monitors political violence in more than 160 countries for risk indicators, and he observes genocide in less than 2 percent of the cases he registers annually. “It’s accurate to assume that genocide is unlikely, even in countries where many of the risk factors are present, whatever you might think those factors are,” he said.

American guilt about Rwanda—and the books, films, and advocacy campaigns that have dissected our inaction—distorts where, and how often, we think we might see genocide. Those distortions have had painful consequences. In 2011, during the presidency of Barack Obama, the United States spent $1 billion to overthrow Moammar Gadhafi, motivated, the administration insisted, by a commitment to protect civilians whom Gadhafi had threatened to kill “like rats.” The intervention, which Obama reportedly referred to as a “shit show” in private, only exacerbated Libya’s civil war.

In 2015, Obama’s ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power, accused a senior official in Burundi of using “language of horrors the region hasn’t witnessed in 20 years.” At the height of a political crisis in Central Africa—one that Westerners, who remembered “Hutu” and “Tutsi” from 1994, were quick to sketch in ethnic terms—Power accused the official of threatening the population with “extermination,” because he’d used the verb that Rwandan extremists had employed as a euphemism for killing in 1994—at a different time, in a different country with a different political history.

It was a mistranslation in every sense of the word, and not a benign one. Power insisted her counsel on Burundian politics was apolitical, but she ignored that the other people involved—namely, Burundians—did indeed have politics. Her accusation served the interests of the country’s political opposition, but it shocked other Burundians, who felt the ambassador’s personal preoccupation with genocide—with A Problem From Hell, she’d literally written the book on US inaction in Rwanda—torqued her interpretation of their language. Though human rights groups documented political violence, including disappearances, no mass killings took place in Burundi. Power’s advocacy, however, convinced the ruling party that the international community was far from impartial, and in the ensuing years, it kicked out UN human rights observers, World Health Organization officials, and international humanitarian organizations.

Even during a bona fide genocide, the memory of Rwanda warps US foreign policy. In the mid-2000s, the Save Darfur movement pushed American officials to avoid “another Rwanda” in Sudan, where government-backed militias emptied villages and killed hundreds of thousands of people. The government was run by Muslim Arabs; the violence was perpetrated against Black Sudanese, many of them Christians. With that, the script was written.

Activists “looked back a decade earlier to a different country, to a conflict that had different dynamics driving it, thinking that if they could copy-and-paste to Darfur…you’d get success there, where Rwanda had been a failure,” Rebecca Hamilton, the author of Fighting for Darfur, told me. In Rwanda, US officials avoided the word “genocide”; in Darfur, activists pushed them until the State Department used the label. US officials had gutted the UN peacekeeping mission in Rwanda; Darfur activists demanded US support for a UN deployment with the authority to use force to protect civilians. US officials had privately scolded Rwandan leaders for seeming complicit in the slaughter; Darfur activists pushed for public accountability, and Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, became the first sitting head of state to be indicted for genocide. But none of those measures ended the conflict, which continues to this day, and scholars have argued that some of them, particularly the indictment, made it worse by deepening Bashir’s resolve to stay in power. (Sovereign immunity has generally protected sitting heads of state from being arrested, even if they’ve been indicted by the International Criminal Court.)

“There was so much energy focused on moving [the] US political system, and a total discounting of the work that local [Sudanese] political dynamics were doing and could do,” Hamilton said. “People could have named the key players for making things happen in the US political system before they could name any Sudanese actor, other than Bashir himself.”

Meanwhile, US activists overlooked Sudan’s own protests against Bashir, whose violence in Darfur was no outlier; he built his 30-year grip on power by destabilizing the poorer regions of the country and strengthening the wealth and infrastructure of the capital. “The Sudanese were, certainly in the initial stages, completely discounted. And yet at the end of the day, it was the Sudanese people themselves who managed to actually overthrow Bashir—something that those who were advocating from outside of Darfur could only ever have dreamed of,” Hamilton said. Bashir was ousted in 2019, after months of protests across the country and a weeks-long peaceful sit-in in downtown Khartoum.

International activists failed in Darfur because they ignored the same thing diplomats ignored in Rwanda: that Africans, too, have politics. It’s no accident that the story most Americans know about the genocide in Rwanda is about America. Here, we believe, we have politics; over there, we quietly assume, primal instincts crowd out political thought. Even when American human rights advocacy fails, it erases African agency. How else, after all, could we still seem powerful enough to solve the problem from hell?