People have strong feelings about Jay Caspian Kang. He is one of the few writers currently working in America who filters many disparate subjects through a singular intelligence—sometimes brusque, but always thoughtful. His most recent endeavor, a newsletter for the New York Times Opinion section, has tackled an incredibly wide range of subjects: NFTs, YIMBYs in California, and Chinese immigrants in the Mississippi Delta. He began his career writing about basketball, gambling, high school debating and identity politics, and, memorably, a highly controversial ranking of pop divas. He is also the cohost of a podcast, Time to Say Goodbye (with journalist E. Tammy Kim and historian Andrew Liu), that discusses current events and politics in Asia and Asian America with a distinctively left-internationalist lens.

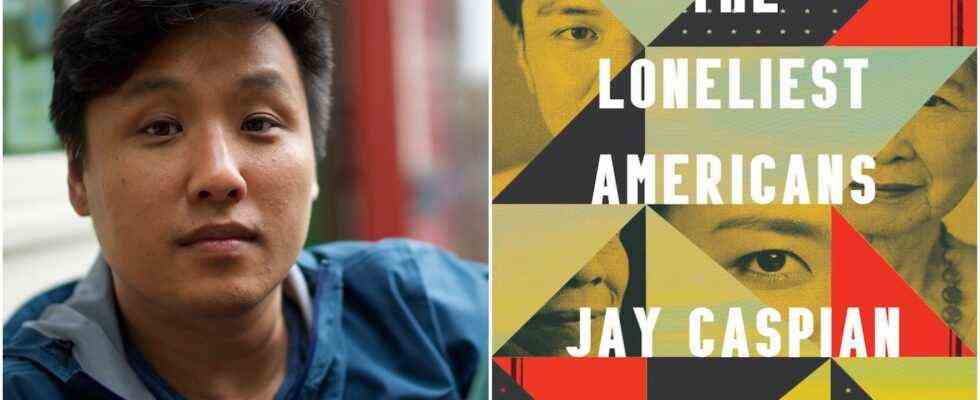

Kang’s new book, The Loneliest Americans, explores how the concept of the Asian American developed after passage of the Hart-Cellar Act in 1965, when immigration restrictions were finally lifted and those with enough resources and the correct qualifications could move from Asia to a country that had effectively prohibited them from coming for the better part of half a century. Part memoir, part deep reportage, The Loneliest Americans traces the evolution of a reactionary identity politics preoccupied with securing whatever few gains upwardly mobile Asian immigrants have been granted, and attempts to understand the neuroticism and sense of complicity that second-generation Asian Americans feel about their contested position in American racial and class hierarchies.

We talked about actually existing Asian America, Joan Didion, and pushing people left. For the longest time, Kang told me, he had trouble explicitly incorporating his political commitments into his work. The Loneliest Americans is one of the fruits of that struggle.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Rosemarie Ho

RH: You confine yourself to discussing the historical development of Asian America after the passing of the Hart-Cellar Act in 1965, and specifically the identity struggles that come out of being relatively recent immigrants into a country with a rigid racial schema. Why trace the specific history of Asian professionals immigrating to the States and their children who struggle with assimilation and not, say, the gold miners who came in the 19th century?

JCK: There’s two types of Asians, or two Asian Americas. The first one is very small. That doesn’t mean it’s not important, but the number of people who can trace their roots here back four or five generations, six generations, eight generations ago is a minuscule portion of the population of Asian Americans. Those people are very far from the experience of the immigrant enclave or even of suburban Asian Americans, all of whom probably came post-1965. You have this group of people who came into the United States right after a time when that first part of Asian America is becoming pretty radical, at least on college campuses—the era of the Third World Liberation Front, Grace Lee Boggs, Yuri Kochiyama, and the creation of this radical Asian American identity, which ends up being where the term “Asian American” comes from.

But the way that we’re taught to think about this is that all those people who came over and got off the boat and didn’t speak English, who are trying to find a job, have some connection to the radical people on college campuses, outside of the fact that they look the same or have similar last names. I don’t think that there is any connection between those two. My parents might know about it now because I’ve written about it, but if you’d asked them “What do you think about Grace Lee Boggs?” or “What do you think about Asian America?” when I was growing up, they’d be like, “We’re not Asian, we’re Korean.” Maybe they would sometimes say they were American, but their first thought would be “Korean”—being “Asian” never even came into it. I think that’s the experience of the vast majority of Asian immigrants in this country: They mostly have pretty shallow roots here. [Post-1965] Asian Americans claim the Chinese Exclusion Act and stuff like that, but there’s not a direct line of descent in the same way Black people in America can make a direct causal link between slavery and where they are today.

RH: The title The Loneliest Americans comes from a line in a great 2017 New York Times Magazine feature you wrote about the hazing death of Michael Deng, a Queens kid—but unlike that piece, where you say that the term “Asian American” is “mostly meaningless,” you lean now into dissecting the manifold ways Asian America exists, tenuously. What changed? Why engage?

JCK: Well, I still think it’s pretty meaningless as a term. I think the people who feel a lot of investment are the people who write books about it—

RH: You wrote a whole book about this!

JCK: I did, I did, that’s true! I just don’t think that it exists as a political category, let’s put it that way. It’s a demographic description right now, and depending on who you ask, the limits of that demographic can shift by billions of people. Do you include Indians and Pakistanis? What do you do about Southeast Asia? But in the end, essentially, when you’re talking about Asian Americans, most people think you’re talking about East Asians. There doesn’t seem to be an effort to make a solution to this problem; the term is just whatever the person who says it thinks it is at the time.

I think it’s perhaps more politically meaningless at this point—even after the [recent anti-Asian] attacks, which did make me rethink a lot of stuff, because I was like, “Well, is this gonna be a moment where the new Asian American identity comes out?” Even if it’s only amongst, let’s say, the elites or people in college or whatever, it’s still significant—that’s what happened post–Vincent Chin, where you have this consciousness movement.

The fact that [this shift] hasn’t really happened is even more evidence to me right now that [Asian American as a political identity] doesn’t exist right now. There’s no coherency to it, there’s no thought about it—it’s just a bunch of individual people being scared. But none of those people really feel enough of an attachment to one another to try and create something that is not just within their ethnic groups. Maybe I’m wrong! Maybe these things are forming, but I don’t see them. Do you?

RH: I do think that your podcast [Time to Say Goodbye] indicates some level of consciousness raising or coalition building within Asian America, even if it doesn’t necessarily translate into direct organizing projects. People are grasping at this nascent thing! If you’re interested in Asian American issues, what do you do? Do you join an organization? If you join an organization, it’s most likely not an explicitly Asian American one; it’s most likely something channeled, like tenant organizing in Chinatown or specifically country-of-origin-type organizing.

I find it interesting that this book basically argues that the only political movements that exist and that we can name as explicitly Asian American are, broadly speaking, the Men’s Rights Asians (MRAzns) and anti–affirmative action Asians—people who want to keep standardized testing. Why is that?

JCK: There are two reasons why they’re powerful. The first is that they’re much better at organizing. The anti–affirmative action groups in particular are very well organized. There’s not that many, but there’s enough of them, and they’re really good at using WeChat, for example, to organize. They’re really good at being loud, they’re really good at finding money, and they’re really good at tapping into the right wing to organize and fund their platforms. That’s how they can bring a suit that will probably reach the Supreme Court, right? That’s how they can get a bunch of right-wing legal minds to join their cause.

Now, there’s no real equivalent to that on the left. Like you said, most of the left organizing in Asian American spaces is trying to actually help poor people. It’s ideological in its foundations, but in practice it’s like, “OK, how are we going to get these laundry workers better protections?” or “How are we going to get delivery workers the right to use the bathrooms?” Those are the types of left organizing that do exist. I think all that’s very important, but it’s not the big-ticket things that the right does. I do think also that there’s this sort of quiet tolerance of those types of movements, even from people who are presumably progressive or liberal. I think that is also true for [the movement to defend] Peter Liang [the New York police officer who shot and killed a black man, Akai Gurley, in 2014]—that there was much more support for that type of political action than people were comfortable saying.

RH: Right. I think you draw this out really starkly in the book, inasmuch as you basically say that, moving forward, either Asian America keeps pushing reforms for the bourgeoisie that the right wing attaches itself to, or little things for the working class. But which conception of America is more appealing to people? You’re worried that the meritocracy version will basically win out. What do we do?

JCK: I actually think there’s a clear path out. But it would require people like myself, who are upper-middle-class, upwardly mobile, and have access to broad messaging campaigns or political power, even capital, to resist and commit class treason against themselves, and to try and recenter the idea of Asian American politics—if it exists at all—around the concerns of the working Asian poor, of which there are many. Whatever survey or census you want to look at, obviously they all say the same thing: Asians are either rich or they’re very poor. If we can just not center politics within an extremely privileged space anymore, and if we can talk about the poor, then the idea of “our people” makes sense—we’re no longer erasing all of the less fortunate.

Part of the reason why people of all races feel alienated from Asian American politics, and why avenues of solidarity are so difficult to set up, is that forward-facing Asian American politics are about the upper-middle-class Asian American navigating Hollywood or the corporate workspace. It is totally cordoned off to an already privileged group, and that does broadcast the idea that all these people are privileged. The other part of this is that I think what a lot of Asian progressives want the most is not acceptance from white people, but to be seen by other minority groups as also struggling. If that’s the desire, if that’s the idea of solidarity, you can’t build that through the concerns of an upwardly ascendant upper middle class that is obsessed with Hollywood representation. Like, who gives a shit?

It just requires a total recalibration of the focus of the politics. I thought that maybe it’d happen after the Georgia spa shooting, but it went right back to affluent Asian media people talking about how they’re upset because they Anglicized their name or how kids were mean to them in school. I don’t think it’s necessarily hopeless; I just think we have a long way to go. If the book can be an intervention and perhaps inspire somebody much more charming and eloquent and forceful than me to start pushing, I’d be so happy.

RH: You talk about, in part, what I would broadly construe as socialist or even communist organizing—and I’m not just talking about the Third World Liberation Front. Specifically, you talk about your old professor Noel Ignatiev, who was explicitly a communist, who organized in factories, and you reflect on his work on whiteness. There is, I think, a tradition of Asian people in America who pursue socialism and communism. In what ways do you consider yourself and your work to be engaging with that tradition?

JCK: The book is inspired by Noel; it’s a lot about Noel’s ideas on labor, but mostly it’s about Noel’s life, which was spent doing things that I thought as an 18-year-old, when I first met him, and still think today were heroic—going into factories, living through it, really observing and trying to understand what is happening, and then telling people about it, seeing the real relations between white and Black people on a factory floor. In a lot of ways, this book is about him—it’s a reflection on his life, on his work, and is hopefully an update on how it applies to a multiethnic United States that’s not just Black and white.

The thesis that whiteness is in relation to Blackness, and how that is pounded out through labor conflict, is everywhere in this book. That type of thinking informs everything I do. The way I would like to approach it for my career is not to come at this with the perspective of a Marxist scholar or whatever; I think that my job is to try and write things for a broader audience, and to make the argument for people who aren’t already convinced that there are different political possibilities out there than the ones that are in front of them, in a way that doesn’t compromise the ideas or the politics. I don’t know if that’s possible, but that’s what I’m trying to do.

RH: Ignatiev’s big thing is to include the actual personal stories of the workers he worked alongside or organized. I was curious—why not write a chapter about the working-class Asians you do mention that we should center?

JCK: That’s a very good question. It’s one that I’ve thought about quite a bit, and I’m glad you asked that, because it is the one criticism of the book that I spent the most time worrying about while writing. It’s not like the thought didn’t cross my mind while I was writing, and it’s not a product of laziness that I didn’t, for example, spend a month with delivery workers—it’s not that much more work than researching how [the New York City neighborhood of] Flushing was built, for example. The first reason was that I think that’s basically a separate book; there is a book to be written about the real Asian America, right, which is people who are totally expendable. My thought is that it feels extremely patronizing to excavate the “hidden” Asian America and do an anthropological study without a central organizing argument around it. I just think I haven’t figured out how to write that book right now.

I also think this piece is a conversation with myself, my parents, and people who grew up like me, who are part of this upper middle class—it is an intervention for us to please stop doing politics in the way that we’re doing them now. Writing a chapter showing that there are people living another way, I’m not sure it’s necessary—like, we all know that, right? We’ve all been to Sunset Park [in Brooklyn], for example; we’ve ordered Chinese food to our apartments, and we see the guy who looks like us, who is poor and lost in America in a way that is unfathomable to us. We know that these people exist—and if we don’t, then we’re lost.

RH: This book is a meta-history of the media landscape in its own way, through your discussion of your own career and how the media covers police brutality and so on. Do you feel entrapped by the white journalistic establishment’s need for writers to explain race to its audience? And I guess I’m going to ask you that now: How does it feel to basically still be one of the few widely respected or known Asian journalists writing about race in America right now?

JCK: It comes and goes, but I think I wouldn’t be writing about race if I wasn’t interested. My journalism career actually started in sports, so I could have just continued doing that, but there is something that takes place where you do these calculations, and you try and figure out the things you have done that get a lot of responses and what you think you’re good at. Three years ago, I had felt like I was being asked to write about every Asian thing, and I resisted it because I didn’t really have an opinion on a lot of the stuff that was happening. Like Scarlett Johansson taking a role who’s supposed to be East Asian—my opinion on this is: Who cares? And so, if I felt constricted or if I felt pigeonholed, it was because of those types of requests, which did come in quite a bit—not really from the people that I worked with at the Times, as they know me, but just from other people who might not.

I also felt constricted by the fact that I couldn’t figure out a way to express my politics in my writing. I think that for the first half of my career, I wrote a lot of pieces that were basically just about my feelings about things. And so I was feeling a whole lot of internal angst about not wanting to write any more pieces about how it feels to be Asian. I don’t think about it that much; I don’t walk around thinking about what it’s like to be Asian all the time. And yet, if you read my work, it seems like that’s all I think about! I wanted to, at that point, have some sort of transition into implementing more of my political outlooks on life—which, at that point, I did feel confident in—in my work. It’s taken a lot of forms, but one of them is this book, which I think is much more explicitly political than even the article it’s based on. Another is doing the podcast with Tammy and Andy. Our goal has always been the same—that if there are people who feel like we do about these things, they have something to listen to that will help them out. That’s what I’m trying to do now.

RH: Whenever you talk about your writing, you always talk about being honest. What does honesty mean to you as a writer?

JCK: I think it’s the most important part of being a writer—it’s the sort of writing I find myself most attracted to, even if I think it’s poorly written. I prefer a really honest mess than a very pristine thing where I feel like the person is lying to me the whole time. It’s especially important now, when I think there is a type of ossification, or at least a codification, of a type or style of politics where one’s actual beliefs—or one’s ugly beliefs—are totally obscured. A lot of this happens online, but it also happens, I think, in writing as well, in actual pieces. There’s this clean line of accepted beliefs, and the person hovers above all of them; just expect that they have all the right opinions about everything, and as long as they can turn around a very conventional piece of journalism, then nobody questions it, and those people end up being, like, very cool.

I just find that to be so boring, personally. The stuff that was always exciting to me was the stuff where I felt like: There is somebody going through a breakdown, something is very wrong, and they’re confiding in me what was wrong. When I was young, I thought Joan Didion was doing that, but then I realized later that Didion was actually lying to me and withholding her feelings in her journalism. But, you know, that’s why you move on. I kind of appreciate it when Renata Adler says things that are totally out of left field or, if you think about it, almost cancelable—like when she goes to Selma and she’s like, “These people are not marching in a very organized way.” It’s like, “What are you doing?!” But it’s honest; I find it compelling. Or when Jon Krakauer breaks down this tale of Chris McCandless in Into the Wild and talks about how he understands McCandless because he himself at times wanted to climb up a giant mountain and throw himself off. There’s this thing he sees in McCandless that he identifies with strongly, and that’s why he wrote the book—because he was sick of seeing people say that the latter was stupid and selfish, even if he thinks the same thing. He at least understands why McCandless went out into Alaska. That’s the type of honesty I aspire to with the book and the stuff that I write. But it’s hard. We battle all sorts of forces; there are a lot of incentives to write things differently or take different political standpoints. I guess I’m not immune to any of those, and it’s up to the reader to think about how honest it is. I’ve made my best attempt.