Jennifer Homans is a dance historian and critic. Her first book, Apollo’s Angels, traces the origins of classical ballet, from Louis XIV’s performances as the Sun King in Renaissance France to its arrival in New York in the 20th century. Ballet, she writes, is rarely transcribed or recorded through text. Instead, it is passed down from dancer to dancer. A trained dancer herself, Homans’s work demonstrates how ballet exists within both the mind and the body while also revealing how retelling ballet’s history is another way of illuminating the history of empire.

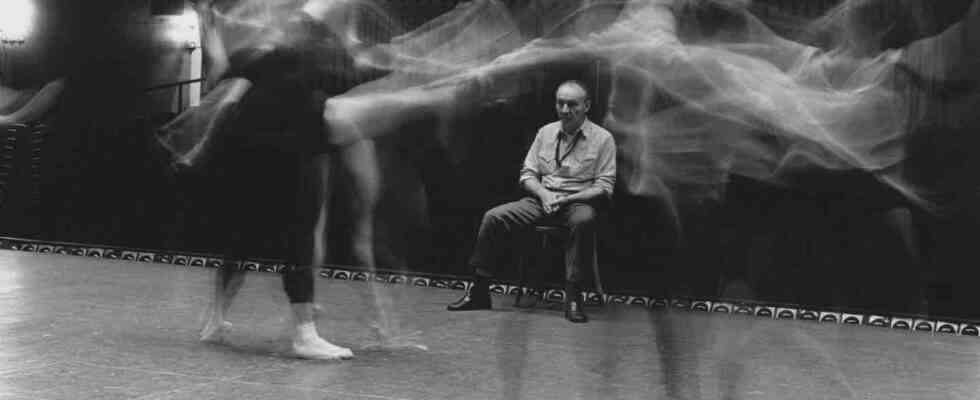

Her new book, Mr. B, homes in on the life of one of the 20th century’s most prominent choreographers, George Balanchine—the Russian face of American ballet. She moves through his youth in Imperial Russia to his defection to Western Europe (Paris, London, and Weimar Berlin), then finally to his arrival in New York in the 1930s. Homans also traces Balanchine’s far ranging influences, from Spinoza to Goethe’s Faust to icons of the Orthodox church, and explains how they gave Balanchine “a way to spiritualize the body and to elevate it.”

Balanchine’s work intersected with many figures in 20th-century modernism as well. He carried on a friendship with W.H. Auden, and he collaborated with Chagall, Picasso, and Matisse in the making of backdrops for his ballets during his Ballet Russes years. But above all he created his own world of classical ballet, or, as he called Lincoln Center (the headquarters of his ballet company, City Ballet), his church. Along the way, Homans introduces us to many of the personalities in Balanchine’s life: We see Lincoln Kirstein, the art savant who ran most of Balanchine’s enterprises, retrieve plundered art from the Nazis after World War II, convert to Catholicism, and storm a ballet rehearsal in full army uniform in a fit of madness. There are correspondences and dinners with the composer Igor Stravinsky, a father figure and collaborator of Balanchine’s. Then there are the many remarkable dancers he fell in love with (among them: Tamara Geva, Alexandra [“Choura”] Danilova, Maria Tallchief, Tanaquil le Clerq, Diana Adams, and Suzanne Farrell). Homans offers an intimate portrayal of an artist with a sometimes megalomaniacal persona, who fell in love with the “eternal feminine” he saw glimmering within the souls of his dancers, even as he declared himself (quoting from a Mayakovsky poem) “a cloud in trousers”—more Aquarius than man, made of “water and air.”

I talked to Homans about her new book, her time as a student at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet, grief, and the metaphysical side of ballet. This interview has been edited for length and clarity

—Dilara O’Neil

And when he died, I just remember being at the State Theater. And we were all there. I don’t even know how I got into this performance. I must have bought a ticke. And just watching Suzanne Farrell do Symphony in C second movement, I was really crying. It was an astonishing event, because it was a community of people coming together. It wasn’t like the usual theater where everybody’s sitting and you don’t really know the people around you necessarily. It’s not that we talked, it’s just that we had a feeling of like, “Oh, my God, we’re all here together.” So there was that.

And then the funeral itself: it was one of those moments where so many of us felt a sort of deep cultural loss—which affected everyone involved. I didn’t really know him, but I was deeply affected by it. And the funeral was a kind of a performance, it was like a performance of the whole project of all the people who were involved in this endeavor, because they were all there. When I went back to reconstruct it and tried to describe it, I relied a lot on pictures of the event. I had some pictures in my own head, and I had a lot of different accounts from the dancers. One of my favorites was the image of Danilova walking down the street after the hearse, looking lost and following after it.

It leaves me a little bit speechless, those events. I knew that I didn’t really understand what had happened to me in terms of being affected by Balanchine’s work and by his presence; he was around when I was there, and I would watch rehearsals and, you know, sneak in and peek in, like everybody else. But I didn’t really understand that I was part of something that was much bigger than I knew at the time.

As a teenager, I got dropped into it. I didn’t plan it: It was an accident. And there I was. I just happened to be obsessed with ballet and wanted to be a dancer. And then I ended up in this place where there’s this genius at work. And to me, it was normal, you know, what else would it be like? Except that I knew that this wasn’t like most other performances. So I knew it was exceptional. But I didn’t know why or how, and I certainly didn’t imagine at that time that I would ever return to it. And through writing.

DO: This was before you wanted to be a writer.

JH: I always sort of wrote things down when I was at performances, and I came from an academic family. I spent a lot of time at the New York Public Library [the theater branch, which is across the street] when I was training at the School of American Ballet. I would go over there and try to figure out what was going on. What was this thing that I was studying? And I would watch videos, and I would read books. I got invited to Danilova’s for tea. And for years after that, I would make it my business to get invited again. I was fascinated. At that time I was just listening, I didn’t write any of it down, but I remember a lot of it.

DO: Dances, as you say, are not transcribed; they are handed down from person to person. How do you think your background as a professional dancer, and former SAB student, influenced how you were able to write about these ballets?

JH: Writing about dance is something intuitive for me, which comes, I think, from having been a dancer. I try to see it from the outside, as the audience would, and also to imagine what it is like to do it from the inside of the body, in the movement. It is an act of translation—having a nonverbal sense of a work and then striving to find words that might convey what it is.

DO: Can you talk a bit about your practice of melding archival research with more permeable subjective memories, both yours and those of Balanchine’s dancers?

JH: Archival and oral history can be used to compliment each other, I think. Memory is notoriously inaccurate, but memories—and the person doing the remembering—are also a form of information, which can be balanced by archival sources from the time. The best, of course, is when the interviewee also has diaries or letters from the time, which can jog memory and add another layer of evidence.

DO: It’s funny that you say you were always reading while you were dancing, because it also seems like, from your book, that Balanchine was also an inveterate reader, and you paint such a rich picture of everything he was interested in and what left footprints in his mind, from Mayakovsky’s concept of byt to Nietzsche’s influence.

JH: That was a big discovery for me because I have grown up in what I think of now as a kind of mythology of Balanchine, which he in part created, which had to do with a sort of modernist set of chants: “don’t think, just dance.” It’s all in the work, we don’t need words. So when I started to understand, and come across the evidence, that in fact he actually read a lot and knew quite a lot about both literature, everything from Russian literature to Goethe, to reading bits and pieces of Spinoza and Sufism. There are interviews with him that show very clearly that he was immersed in Nietzsche and Hegel.

Byt, the idea of something that is settled in every day, is stuck and congealed in, was something that he really internalized and was very committed to avoiding all of his life. He was very worried about becoming bourgeois, and he lived very simply and didn’t care about money, and he didn’t want anybody else to care about it either. For his dancers, his artists, it was all about being on the edge—he didn’t want to settle into a tradition or settle into a way of being. It was a commitment to being avant-garde. Which is a way of being alive, really. That’s what he was interested in, like, don’t go to sleep. Wake up! Don’t sleepwalk.

DO: Balanchine always thought about how dances should be like butterflies, here and then gone. But that obviously changed throughout his life because he brought back dances all the time, and through that oeuvre created a legacy.

JH: “Legacy” really was not a concern of his, though. The only thing he was worried about was the Soviets getting hold of everything.

He brought things back because he needed a repertory. Once he had a company, once the New York City Ballet was established, they needed a repertory every year, so works came back, but they changed. They weren’t always the same. It was just a fact for him, one of the strengths of dance was that it was ephemeral, and that it was absolutely here and then gone. So that, it’s the most alive thing of all. It’s in the present moment. It’s not even one beat further or one beat back; it’s right this second. And then, it’s kind of, what is pieced together of all those seconds is a dance. And this was all connected to his interest in time, how time works, and how we can measure time visually with and through music.

He loved the fact that as he put it, you do a step on one dancer, and it might look spectacular. Or whatever it is, you are moved by it. And then you put that very same step on another dancer, and it’s nothing. So it’s not the step, it’s the person and how they do it. Ballet is actually one of the most individual and individualistic arts in his hands, because it’s not rote. Performance for him was not a kind of depersonalization. Even though there is an effort to remove ego. It’s a real embodiment of that person.

DO: He talks about his dancers working on their “statues” and perfecting their physique, comparing them to the statues of gods in ancient Greece. But he’s not exactly recalling antiquity right? He’s speaking through the neoclassical lens, recalling Nietzsche’s reinterpretation of the Apollonian and Dionysian.

JH: He was interested in the idea of a statue and the chisel. The sculpting of the body is a way of describing what he’s doing when he reinvents classical technique. I think it’s a jumping off point. He had an interrupted education because of the war in Russia, the First World War, and the revolution. So his education was really in his life and what he chose to read. And I think the whole engagement with Nietzsche, in particular, and with Plato, and the whole literature of antiquity had to do with navigating those gaps, filling in what he needed.

The whole Russian revolutionary culture is really important as well—he felt he was part of a real avant-garde scene. That feeds him for the rest of his life. He’s read Goldovsky, Meyerhold, Bloch, and as you’ve said before, Mayakovsky, and of course he’s read the Russian symbolists and he’s involved in poetry. These are the people who are in a moment of extraordinary destruction and change. And so everything’s been thrown down and there’s a lot of violence. There’s basically the breaking of a tradition, the breaking of bodies, the breaking of everything around him that he had thought to be solid. It’s a real sort of Marxist moment, all that is solid melts into air, except that it melts into violence and a new regime.

The choreographic notes that I found are a sign of that because they not only refer to Spinoza, but then they move on to film, and they talk about the sorts of ways in which he seems to see things that other people don’t see, and the project of actually directing someone’s eye to a specific moment in music and movement.

I would even say that the “neoclassical” was a word that he didn’t particularly warm to. He was making dances that he felt were more ranging, and he wasn’t interested in labeling what they were, because they were different every time and his lexicon was so vast: everything from surrealism to expressionism to a deeply romantic pas de deux or a whole ballet.

DO: The first half of Mr. B is all about everything he absorbed, including the mechanics of machines and Weimar puppets. By the end of his career, you take a step back and realize what he’s done. You say in the book that Balanchine’s girls barely even look human because they’re so angelic, but also so technically trained.

JH: Yes, they’re so changed—it is a project of metamorphosis, really. It’s a project of transforming the human body, and the human being. This is like, at the level of muscle and bone. You’re actually trying to move bones, change the way you move. And that’s a pretty radical project, as well as troubling.

DO: In your previous book, Apollo’s Angels, you highlight how ballet has traveled from empire to empire through the marriage of royals. Then, in this book, you pick up in the 20th century as it travels through defectors and immigrants, as part of Balanchine’s plight. Mr. B emphasizes how American dance was founded on Central European refugees and immigrants. What was the relationship between dance and geopolitics?

JH: When I started to do this book, and I started to talk to the other dancers who were with Balanchine in the early years, or read about the ones who had died, I started coming up against this theme of migration over and over again, because I didn’t just ask people about their time with Balanchine. I really wanted to know about their whole lives, how they had lived and how they got there. I was able to excerpt that in the chapter “Company”—the range of people that came to NYCB, from people who were coming from out west, and these sort of early American families, and farmlands in some cases, or Salt Lake City and Mormon culture. But over and over again, I came up against the Central Europeans, these families who had come in one way or another, at one time or another, and I think because those cultures understood and admired ballet, they were just more likely to send their kids to these dance schools. And so for whatever reason, they were drawn together, these young dancers and Balanchine.

And so you get this sense that the dissolution of empires and the ways in which the First World War, the Russian revolution, and everything going on in Europe, like the Armenian genocide, is putting people in motion. They’re leaving; they’re refugees. There’s displacement and exile on a vast scale, and many of those people ended up in the States and in New York. It was astonishing to me to look at the numbers of people Balanchine worked with who were from this background. It was an interesting product of the disruptions of the 20th century.

DO: What made classical ballet American then?

JH: I think it was partly the immigration and exile quality of Balanchine’s early company. Companies, we should say, because there were so many before something finally took root. And the ways in which he was absorbing the modernism from Europe and the interest in the motorcar, the airplane, the train, the speed, the mechanization, automatons, the idea that there was going to be a transformation of society. He took everything from the Russian Revolution to Bauhaus to Diaghilev to Weimar culture. Then in America, he absorbed popular culture: Hollywood, Fred Astaire, and other subcultures he was witnessing in New York. He was learning.

DO: It does feel like he was a sponge for culture, and that shows up again and again. He gives Tanny Le Clercq (his fourth wife) The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm. And he went through lengths to work with Black dancers during the civil rights movement, and he read the Frankfurt School. Then he grew to be quite conservative.

JH: Well, he was always conservative. He wasn’t a white Russian because he wasn’t from an aristocratic family. But he was a cold warrior; he was anti-Soviet. And he was a kind of Eisenhower Republican. In that way, he couldn’t tolerate the left’s interest in socialism and communism until Stalin disrupted that; he just wasn’t sympathetic with it at all. To him, it was the most destructive system of all human creativity, and that’s what interested him, which did put him at odds with a lot of people on the left.

DO: Let’s compare Mr. B with Lynn Garafola’s book La Nijinska, both about Soviet dissidents who left Russia. Bronislava Nijinska missed Russia and felt constrained by the West and the market. Balanchine never wanted to go back to Russia and hated the Soviet Union. But I think he also felt constrained by the market. For example, he is furious about the commercials that aired during his televised ballet, and he once said, “A sponsor is not a man, a sponsor is a thing, a toothpaste.”

JH: It’s not that he was a die-hard capitalist or a defender of the free market. What he was trying to define was, as he put it, “my little place,” and to create a sense of the spirit within a society that he thought was free but faulted for its materialism and emphasis on money and external success rather than the world of the spirit, the imagination of the child. I mean, that’s really what The Nutcracker is about. It’s about the imagination of the child.

His version of The Nutcracker is great, actually, because it has the philosophy behind E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story. His real interest is evidenced by the way he did it and the characters and even the ways in which he used Hoffmann’s names, not the later names that were kind of made sugary. But then it’s also got the expanding tree at the end of Act I. The tree is eminently practical. The tree is like, we’re gonna sell tickets for decades because of this growing tree.

And they did, right? And he knew that. He got that. They were like, it’s too expensive—we can’t have the tree. And he was like, that’s the whole point: the tree.

DO: Balanchine’s ballets are partly built on, as you write, Orthodox icons.

JH: I tried to do the icon reference delicately, because it was a Lincoln Kirstein idea. You know, Kirstein believes that Balanchine ballets were like icons. And Balanchine said, of Violin Concerto, that it was his best ballet, like an icon. This idea of the icon is interesting, because it does capture some of what he did. He grew up with this idea of something that doesn’t have authorship but is shaped not just by God but by a human hand, that has a human touch to it. And many of his dances were flat in the sense that they were interested in that concept of not building a theatrical space that had perspective, necessarily, but taking away all the scenery, and using just light, which gives you a whole different sense of dimension, both greater but also flatter. More infinite, but flat. Then there’s this idea of inverse perception, where your eye is not being guided by a movement in the way it is with inverse perspective. So the ballet is actually taking people in rather than showing them something on display. It’s a more intimate form, in a way, and I thought that was a very powerful insight of Lincoln’s and, indeed, of Balanchine’s.

DO: You say in the author’s note that you felt like you had been in pursuit of Balanchine most of your life. What made you decide to finally write the book on Balanchine?

JH: I was going to write a doctoral thesis about the Third Republic of France and leave dance alone. But I just couldn’t get rid of it. I couldn’t leave it. The decision to write the Balanchine book came out of Apollo’s Angels. There was some part of Apollo’s Angels that was already addressing Balanchine. He is a shadow in the book, a kind of guiding figure in a way, connected to my experience; it’s what I knew. So I was trying to understand that, and it seemed like a natural subject to me.

I still don’t understand why it was so powerful to me. Then there was also the very personal aspect, which I don’t mind sharing with you, which is that my husband had just died. And I was in a state of intense loss and grief and some of those dances began to matter to me in other ways that I hadn’t anticipated. I began to sort of think that maybe there was something to Balanchine that I needed right then. I was intuitively drawn toward him, put it that way. I only discovered through research that he had had a life that was full of tremendous loss, and a lot of his dances deal with that and use that as a kind of implicit subject. There is death and grief, and it’s implicit in what dance is itself, here and gone—like a life. So that was another reason I went back to Balanchine, knowing from the beginning that I was taking on something huge. I didn’t even know how huge.

DO: Dancing does feel to me, as Balanchine was always talking about, like reaching for the light of life, of consciousness. But it is also about different kinds of grief, from the anticipatory grief of knowing one cannot dance forever to depictions of mortality. You make the case that Balanchine was trying to choreograph his own death, from Don Quixote in 1965 onward.

JH: I began to see that life starts with a birth, of course, and there’s something very tangible and physical and real about that. But as the person becomes an artist and moves through his life, things start to move from the real to what he called the realer than real, right to the immaterial, the material to the immaterial. And so, there’s a way in which life moves into the imagination. That’s why I ended the book in a dance, because I felt that that’s where he lived. That’s really where he lived. That’s where they all lived. They were the ones that gave themselves to it fully, you know, and so they’re in that experience of living in that sort of heightened reality. That is a theatrical reality, just kind of extraordinary, and very, very much like, it’s like the undercurrent of the life we all live, right? To some degree, we’re all there. But he was really there. To the point where it was the most important thing in his life, more important than himself. The realer than the real—the metaphysical, the theatrical—starts to become something spiritual: It becomes another world.

DO: He was a cloud in trousers.

JH: He was a cloud in trousers! I almost called the book that, but we didn’t.