The story of Doral began as an immigrant’s dream. In the nineteen-fifties, a Polish real-estate developer and his wife set their eyes on a vast swampland, where they planned to construct a premier golf course. The resort, which they named the Doral Hotel and Country Club, attracted scores of Latin American visitors throughout the years. Luxury condominiums filled pastures where cows once grazed, and a sprawling downtown area featured schools, parks, and a trolley system. With time, Doral also drew in corporate executives, among them Donald Trump, who made a hundred-and-fifty-million-dollar offer for the club, in 2012, and renamed it Trump National Doral.

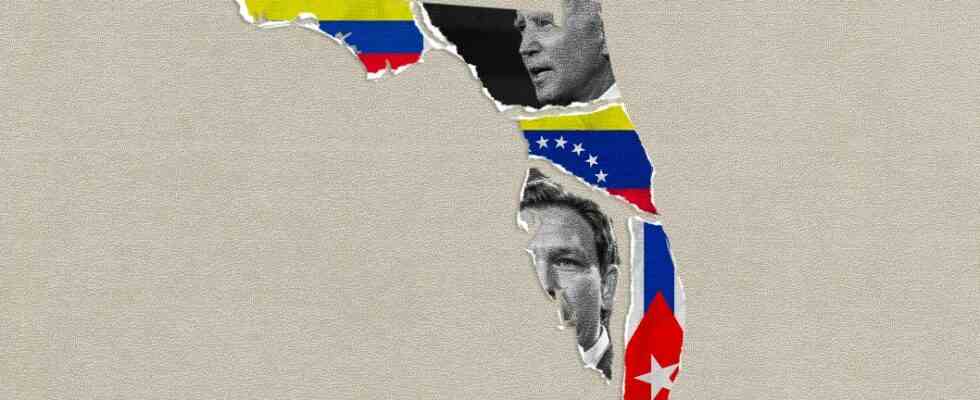

When Trump ran for President in 2016, his resort was seen as a Republican island in Miami-Dade County, an area that has been a Democratic stronghold for decades. That year, Hillary Clinton beat Trump by thirty points there. In the midterms of 2018, Governor Ron DeSantis lost Miami-Dade by twenty points. Democrats’ hopes of flipping Florida long rested in the southeast of the state. But the Democratic Party’s dominance in Florida’s most populous county has been slowly eroding. In 2020, Trump cut the Party’s lead, losing to Biden by a mere seven points in Miami-Dade.

State Democrats issued a clarion call to the Party’s national leadership, urging them to double down on their investment in the county. The opposite happened: after investing nearly sixty million dollars in the 2018 midterm election, Democrats spent less than two million in last year’s race. For the first time in twenty years, Miami-Dade went Republican, with Ron DeSantis beating his Democratic opponent, Charlie Crist, by eleven points. It was clear that the Democrats’ passivity had come at a cost, but also that the G.O.P. messaging on everything from parental rights to the threat of communism was appealing to a growing segment of the electorate.

In the midterms, Florida proved to be the only state in the country where the red wave fully panned out. Along with DeSantis’s trouncing of Crist, Republicans flipped three House seats, and the number of registered Republicans in Florida surpassed that of Democrats—a historic first. Andrea Mercado, who leads the liberal advocacy group Florida Rising, estimated that Republicans had outspent Democrats by more than three hundred and fifty million dollars. Some losses, as in Doral, where Republican turnout far exceeded that of Democrats, were particularly hard to process. Mercado saw them as an unmistakable sign of entrenched G.O.P. gains, and she said that Democrats had only themselves to blame. “The reality is,” Mercado said, “you just don’t win the races that you don’t run.”

This year, Fabio Andrade, a sixty-five-year-old Colombian American executive, spent most of his time in Doral. The city—also known as Doralzuela, for its growing Venezuelan diaspora—is where Republicans, last winter, opened the Party’s first Hispanic Community Center in Miami-Dade County. Andrade is the founder of Republican Amigos, a group of Latinos dedicated to energizing the Party’s base in South Florida. In the months leading up to the midterms, Andrade participated in G.O.P.-run citizenship drives, domino contests, and talks with Senators Marco Rubio and Rick Scott—many held at the community center. He commemorated the liberation of Auschwitz alongside a Holocaust survivor, and publicly denounced the election of Gustavo Petro, a leftist leader, in Colombia. A framed portrait of Andrade was hung next to the center’s entrance, and labelled, in Spanish, “It is important that our party gets involved with our community.”

As if to prove his simple maxim, Andrade invited me to join him at a speed-networking event on a recent night, held in a pub across the street from Trump National Doral. The event drew a crowd of small-business owners who oversee restaurants, insurance firms, and banquet halls. Andrade, who is short and bald, was wearing rimmed glasses and a trim blue shirt, and carried himself like a master of ceremonies. “O.K., cambio!” he yelled to the crowd, signalling that it was time to find a new conversation partner. Like Andrade, the majority of those present were of Colombian origin—the second-largest Latino group in Miami-Dade, after Cubans. His outreach efforts paid off last November. After the midterms, G.O.P. operatives told Andrade that the Party had earned unprecedented support from Colombian voters. “That is huge,” he said gleefully.

Halfway into the networking session, Andrade slid into a booth and urged everyone around him to fill up their drinks. His party’s gains, Andrade told me, hadn’t happened overnight. For him, it went back to the mid-nineties, when he settled in Miami and took a job as an airline manager. Thousands of Colombians were fleeing the country’s protracted conflict between leftist guerrillas and the conservative government; many of them landed in South Florida. At the time, Andrade saw the need to rally local politicians around the Colombian government’s cause. He reached out to members of Congress and lobbied for their support. Chief among the Colombian community’s demands was the need for asylum. “They listened to us,” Andrade said, of the Florida Republicans in Congress. “I guess they were making an investment in the future—making sure they did it right for us, because tomorrow we would be there voting.”

Networking has also been one of the ways that Andrade has drawn people to politics. For two decades, he has been at the helm of a nonprofit whose mission is to help Latino newcomers thrive in South Florida. Its members have praised Andrade’s group for helping them “rebuild their networks” in a country other than their own, and for welcoming them into a new “herd.” Many share Andrade’s views on politics in Colombia, where he supports the right-wing Democratic Center Party of the former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez. He also positioned himself as a go-to person for candidates wishing to court Colombian American voters. In 2018, DeSantis named Andrade his campaign’s hispanic-coalitions coördinator, and he was seated next to Trump two years later, when the former President held a roundtable with Latino leaders in Doral. Andrade is blunt about the motivations behind these overtures. “It’s all about votes, let’s be honest,” he said. “This is not because they love my community—they want to get elected.”

The Colombian community’s growing electoral weight comes with greater leverage over the political discourse. What the embargo is to Cubans, the fight against “Marxist socialism” is to Colombians. And Republicans, Andrade argued, have embraced such issues as their own. In the lead-up to the 2020 election, Trump’s national-security adviser, Robert O’Brien, stopped by South Florida on his way to see Colombia’s President. The purpose of his trip was to announce a five-billion-dollar investment in the country, which O’Brien presented to a group of Latino leaders, among them Andrade. Though such acts are political, they send a strong message to members of the diaspora in South Florida, who are made to feel that there is a space for them at the table. In the eyes of Andrade, these measures are proof that Republicans understand a central “pillar” for the community: their homeland.

Over time, in Miami-Dade, an alternate version of the truth—what some now call la verdad sentimental, or the sentimental truth—has taken hold. For Amore Rodriguez, a twenty-nine-year-old manager at a nonprofit health-care organization, that truth is the sum of her family’s myths. Her mother’s side of the family moved from Havana to Miami, in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, after Rodriguez’s grandmother, a university professor, was tortured for defying the new regime. Like many other Cubans, she found in Miami a chance to start anew and raise a family away from the threat of repression. “We’ve all grown up our entire lives honoring my grandmother and her sacrifices,” Rodriguez said. “This is a reality across many Cuban tables.” Republicans publicly condemned Fidel Castro’s regime and presented themselves as the stewards of freedom. In Rodriguez’s family, support for the Party was considered a matter of principle, more so than choice.

In 2018, Rodriguez graduated from Florida State University and returned home with two pieces of news: she had realized that she was gay, and she also became a Democrat. “They brainwashed you!” Rodriguez recalled her grandmother saying. The older woman was convinced that a communist clique had infiltrated the university halls. To this day, Rodriguez said, her mother’s eyes well with tears every time the subject comes up. Her relatives maintain that the 2020 election was stolen, and Rodriguez has given up on trying to change their minds. But, at times, she makes it a point to call her grandmother out. “Abuela, do you know how crazy it is that you left Cuba because you didn’t have a choice, because you were silenced, because you didn’t have an opportunity to even vote?” Rodriguez tells her. “And here I am being proud about my choice, and you’re looking at me, telling me that I am a shame to you?”

Away from her family circle, Rodriguez found like-minded Cubans yearning for political change in Florida. But they, along with other Democrats in Miami-Dade, say that their party has walked away from the state. After Trump carried Florida by around four hundred thousand votes, in 2020—more than twice the margin that he received four years earlier—Rodriguez and others started the Florida Grassroots Coalition, in the hopes of preventing Republicans from making further inroads, particularly in South Florida.

On a recent Sunday, some of the group’s founders got together at a one-story home nestled among trees, in Coral Gables, to reflect on their party’s losses. Miguel Rodriguez (no relation to Amore), a forty-eight-year-old drama instructor born in Puerto Rico, hosted the meeting at his house. “We all know what happened,” he declared, with an air of regret. A lack of money and strong candidates, along with rampant disinformation, were to blame, he said. But so was political inertia. “We’re talking about a Party that is at once alive and dead,” he added.

Seated around the living room, members of the group recalled what Election Day had been like last November. Their mission was to enliven the Democratic Party’s operation through events and canvassing, but, as they walked the county’s precincts, put up signs, and rallied as many voters as possible, they found themselves asking, “If it were not for us, who would be doing this?” One candidate running for the Florida state legislature ended up leading his entire get-out-the-vote operation with his mother, because there were so few canvassers. In contrast, the attendees all agreed, Republicans’ presence on the ground was consistent and relentless—and so was their messaging.

Just as in 2020, Republicans cast voters’ choice as one between communism and democracy, socialism and capitalism. DeSantis established a Victims of Communism Day on November 7th, a day before the midterm election. “When we comprehend the horrors of the past brought about as a result of this evil ideology,” the Governor declared, hours before the polls closed, “we are inspired to defend our nation’s republican government.”

Amore Rodriguez and her colleagues intimately understood why this messaging worked so well. “The fear of socialism is ingrained in our minds,” Marco Frieri, a Colombian consultant in his thirties, said. After Venezuela’s democracy collapsed, Colombia had borne the brunt of its neighbor’s mass exodus—the two countries share a thirteen-hundred-mile border—and many of his fellow-citizens, Frieri said, feared that Petro, Colombia’s new, left-leaning President, could become a version of Hugo Chávez. “We see domestic politics in the States through the eyes of Colombia,” he said.

In the midterms, though, Democratic leaders made little effort to counter this messaging or challenge its premises. It was as if the notion that their party could be equated with communism or socialism was too absurd to even engage with. Frieri argued that the problem wasn’t just the message—it was its prevalence. “Republicans have a year-round presence,” he said. “They’re peddling their talking points on the radio and inside community centers. We don’t do that—we usually show up a month before the election.”

These shortcomings seemed apparent to the Democratic Party’s leadership in Florida. Earlier this month, the Party’s chairman, Manny Diaz, resigned, after two years in the role. A veteran political operative, Diaz characterized his party in an open letter as “practically irrelevant” in the state. Its strategy relied on building “field operations only around elections” and expecting a vote “without engaging voters.” His hands were tied because the Party had “been starved” over time, Diaz argued. But, as someone who had started his career as an organizer, in the early seventies, and who went on to be elected mayor of Miami twice, he was convinced that there remained a different path—one where the Democratic Party could compete and energize voters, as it had in the past. “Florida is not a red state,” Diaz wrote. “We have a history of extremely close elections.”