This essay is part of T’s Book Club, a series of articles and events dedicated to classic works of American literature. Click here to R.S.V.P. to a virtual conversation about “Invisible Man,” to be led by Adam Bradley and held on June 17.

I first saw Ralph Ellison when I was 19 years old and he had already passed away. On a summer evening in 1994, he appeared to me in the attic of an old manor house on the campus of a small college in the Pacific Northwest. I had encountered him — just as I had Langston Hughes and Jane Austen and Geoffrey Chaucer — by more conventional means the year prior, as an attentive reader of his published work. I read Ellison’s 1952 novel, “Invisible Man,” for the first time as part of a class on African American literature and was drawn to his wise-foolish protagonist with whom, looking back now, I shared more than a passing resemblance: a young Black college student with vague aspirations for leadership who stumbles upon writing as a means of illuminating his identity. Nonetheless, Ellison — like Hughes and Austen and Chaucer — remained intangible to me, aloof, distanced both by time and by achievement.

That could have been the end of it. But, as Ellison was fond of saying, “it’s a crazy country” — by which he meant that the diversity of the American experience often occasions unexpected confluences of people and circumstance. Soon after Ellison’s death, on April 16, 1994, at the age of 80, or perhaps 81 (evidence uncovered after his passing suggests he was born in 1913, not 1914, as he always claimed), Ellison’s wife, Fanny, called on their longtime friend John F. Callahan, my professor, to assume the literary executorship of his estate. Callahan asked me to be his assistant — to help him gather research, photocopy documents and sort materials — which explains why I ended up carrying shipments arriving from the Ellisons’ Riverside Drive address up a creaky staircase to the manor house attic on my college campus. My first task was to unpack the boxes and array the pages contained within across a long mahogany conference table, preparing them for Callahan’s inspection. Among the papers were drafts of Ellison’s unpublished second novel, around 40 years in progress; dot-matrix printouts from his computer, some with penciled edits; and handwritten notes scrawled on scraps of paper and on the backs of used envelopes.

It was while examining one such note that I saw Ellison — or, rather, that I saw past my own veneration of him to the human being he had once been. He was in the texture of the paper as I held it, as he might have held it, between thumb and forefinger. He was in the slant of his spidery script. He was in the faint scent of cigar smoke that had settled into the fibers of the fine bond paper and lain dormant for months, even years, until my nose woke it up. It startled me to realize that I was likely only the third person, after Mr. and Mrs. Ellison — perhaps even the second, after Ellison alone — to have held this page, to have read this note. I felt exhilarated and unsettled.

Though I could not have articulated it back then, I was overtaken in that moment by an ambivalence akin to that which Ellison’s unnamed protagonist expresses in the final line of “Invisible Man” — “And it is this which frightens me: Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” I knew intellectually, because Callahan had explained it, that the lower frequencies were the registers of our shared humanity. Through his protagonist’s voice, Ellison was making the audacious claim that he, a young Black writer in segregated America, could conceive a young Black character with the capacity to speak to the universalities of human experience through the dogged particulars of his own. But I was puzzled, and would remain so for many years, by the foreboding tone of that last line.

I now believe that the narrator’s ambivalence comes from his understanding that speaking for anyone means assuming a heavy burden of responsibility, for oneself and for others. Perhaps it stems, too, from knowing the horrors that some of those for whom he dares to speak, those for whom he remains invisible, are capable. And I know from spending countless hours among Ellison’s papers, now housed at the Library of Congress, that when composing “Invisible Man,” Ellison bore the weight of both his own exacting standards of craft as well as his conviction that he must write fiction that reflected the depth and diversity of Black life as he knew it.

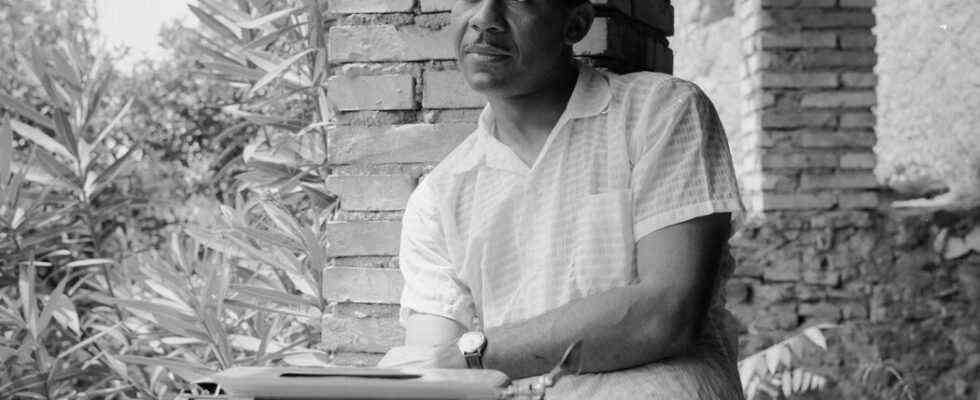

RALPH ELLISON WAS PRIVATE but not reclusive. In a word he favored, he was complex. His letters reveal a man capable of tremendous humor and self-reflection as well as stubbornness and occasional vanity. Born in Oklahoma City, he was a proud Southwesterner to the last, though, after attending the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama, he lived the vast majority of his life in New York City. He was decidedly old-school in his literary passions — his tastes ran from Henry James to Dostoyevsky — but was also a gearhead: an enthusiast of high fidelity audio equipment and an early adopter of the personal computer. The author of only one novel, two books of essays (1964’s “Shadow and Act” and 1986’s “Going to the Territory”) and a clutch of occasional pieces and published excerpts from his second novel, he nonetheless wrote constantly, leaving behind thousands of pages, some of which have now appeared posthumously, including two iterations of his second novel — 1999’s “Juneteenth,” the core of the narrative, edited by Callahan and just released in a new edition; and 2010’s “Three Days Before the Shooting …,” the sprawling sequence of manuscripts and variants that Callahan and I edited together.

“Invisible Man,” for which Ellison is best known, is a big book, in every sense. At nearly 600 pages long, winnowed from more than 800 manuscript pages, it is teeming with characters like a Charles Dickens novel, and has the roving geography of a picaresque, like Mark Twain’s “Huck Finn” (1884). We follow Invisible Man from his high school graduation through his early years at a Southern Black college before his own naïve ambitions and eagerness to please those more powerful than he result in a fateful error in judgment, setting off a chain of events leading to his dismissal from school and his journey through the chaos and excitement of 1940s Harlem. Searching for employment in the city, he experiences the dislocation and uncertainty felt by so many Black Americans who made the move from the rural South to the urban North during the years of the Great Migration. Soon he catches the attention of white leaders of a leftist organization called the Brotherhood that, noticing his talent for moving a crowd, grooms him for leadership. The Brotherhood gives him an identity — quite literally, they assign him a new name that, like his given name, the reader never learns. The action of the novel follows his dawning awareness of his own predicament: that he is an invisible man in the eyes of those who refuse to see him as anything other than a projection of who they want or need for him to be.

Early on in the novel’s more than six-year composition process, Ellison discarded the dominant literary modes among Black writers at the time: naturalism (the idea that environment is determinant of human character) and realism (the effort to represent on the page lived experience in concrete terms), both powerfully exemplified in his friend Richard Wright’s 1940 classic, “Native Son.” That kind of fiction, Ellison believed, was too restrictive to capture the raucous humor, the quality of intellect and the improvisational spirit of his protagonist. He also resisted, and perhaps resented, the impulse of many white critics and readers to confuse Black fiction with sociology. With “Invisible Man,” Ellison set out to write a novel that would be impossible simply to file and forget.

It should come as no surprise, then, that strange and shocking things happen throughout the novel. Blindfolded Black boys, stripped naked to the waist, fight each other in a boxing ring, then collect their reward by scrambling for coins strewn across an electrified carpet while a jeering audience of wealthy white men look on in anger and amusement. A Black sharecropper impregnates his wife as well as, in a dream state, his teenage daughter, then takes an ax to the cheek from his wife in retribution and somehow survives to sing the blues. A paint factory boasts a state-of-the-art hospital with a machine capable of executing a noninvasive equivalent of a prefrontal lobotomy. An eyeball falls out of the dry socket of an incensed party leader, during a leftist committee meeting where a room of mostly white men decide to abandon an entire community of Black supporters in the name of political expediency. A young, unarmed Black man dies at the hands of a white policeman, gunned down in the street for a crime no greater than the unlicensed sale of dancing paper dolls. And Ellison’s narrator, his Invisible Man, writes all of this — Ellison’s novel is his character’s memoir — from his underground retreat in an abandoned coal cellar somewhere “in a border area” of Harlem, illuminated, he tells us, by precisely 1,369 light bulbs.

In 1948, Ellison published an excerpt from his novel in progress, the episode of the blindfolded battle royal, in a journal called ’48: The Magazine of the Year. In those pages, which would become, four years later, Chapter One of the published novel, Ellison generates dissonance between the fanciful details of the scene (the most startling of which is the electrified carpet) and his naturalistic attention to his characters’ bodily functions (they sweat and bleed and even become sexually aroused, though that last detail was excluded from the published excerpt). Enough readers wondered if the story was, in the words of the publication’s editors, “grounded in actual experience” for them to ask its author to write an explanatory note, published four months later under the title “Ralph Ellison Explains.” “The facts themselves are of no moment,” he writes. “The aim is a realism dilated to deal with the almost surreal state of our everyday American life …” With this declaration of literary independence, Ellison demands two remarkable things: that he, and by extension that other Black writers, be granted the full and free exercise of their imaginations; and that realism must necessarily expand to contain the absurdity of everyday American life under segregation and white supremacy: “For all life seen from the hole of invisibility is absurd,” observes Ellison’s protagonist in the novel’s epilogue.

Dilating realism, in other words, means opening up a space in one’s fiction to reach a verisimilitude of feeling inaccessible through a direct account of incident alone. This approach has radical and necessary value for Black writers and writers from other communities for whom the normative patterns of literary representation fail to account for their lived experience. It’s one way of understanding why Octavia E. Butler invokes time travel to revisit the ravages of slavery in “Kindred” (1979). It illuminates Ishmael Reed’s fugitive slave novel, “Flight to Canada” (1976), which broadens its narrative frame through wild anachronisms — his characters take commercial airline flights, they watch television news, they deal with the publishing industry, with talent agents — so that the reader can’t forget that the evils of racism and white supremacy still dog us.

In spite of critical acclaim and commercial success — “Invisible Man” was a national best seller and earned Ellison the 1953 National Book Award, beating out Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea” — Ellison continued to face criticism from those who rejected a novel that did not play by the rules. Reviewing for The Atlantic, Charles J. Rolo praised the book but argued that “it has faults which cannot simply be shrugged off,” the most damning of which is “a tendency to waver, confusingly, between realism and surrealism.” But this wavering is precisely Ellison’s point. Four years after the novel’s publication, Ellison answered a letter from a professor at a small New Jersey college who asked about the novel’s narrative style: “If you go back to the beginning of the book you will notice, after the Prologue, that the action starts on a fairly naturalistic level,” Ellison explains. “The hero accepts society and his predicament seems ‘right’ but as he moves through his experiences they become progressively more, for the want of a better word, ‘surrealistic.’ Nothing is as it seems and in the fluidity of society strange juxtapositions lend a quality of nightmare.”

ONE OF THE MOST NIGHTMARISH — and therefore most surreal — scenes comes near the novel’s end. The final chapter begins with gunshots — “like a distant celebration of the Fourth of July” — in retaliation for the murder of Tod Clifton, a charismatic Black youth leader of the Brotherhood who was shot to death in Midtown Manhattan by a white policeman. Following Clifton’s death, Ellison’s protagonist leads the funeral procession and delivers the eulogy for his slain friend, repeating his name time and again to the crowd. “The story’s too short and too simple,” he says. “His name was Clifton, Tod Clifton, he was unarmed and his death was as senseless as his life was futile.”

As night descends on the city, the people rise up, some in anger over Clifton’s murder; some inspired by the protagonist’s oration; some incited by Ras the Exhorter, now the Destroyer, a magnetic Pan-African community leader who opposes the Brotherhood — especially the protagonist, whom he sees as a race traitor — and channels the people’s rage as a weapon; others take to the streets simply to revel in the chaos. As his nameless narrator walks through Harlem, Ellison floods our senses with impressionistic images, illusions that never quite resolve into tangible form. Looters push a bank safe through the streets amid active gunfire between protesters and police; a ricocheting bullet grazes the narrator, who passes a dead man lying in the street, a crowd gathering around the corpse; a milk wagon, pulled by several men, becomes a makeshift throne upon which “a huge woman in a gingham pinafore sat drinking beer from a barrel” belting out the blues; pale and naked female figures suspended from lampposts, a macabre spectacle, reveal themselves to be store-window mannequins hanged in effigy.

In perhaps the novel’s greatest dilation of reality, Ras makes his way through the streets of Harlem on horseback, dressed as “an Abyssinian chieftain” and brandishing a spear against the white policemen. Ras, the narrator observes, is a “figure more out of a dream than out of Harlem, than out of even this Harlem night, yet real, alive, alarming.” When Ras sees Invisible Man, he cries out “Betrayer!” launching the spear at him, missing wide. The narrator makes one final rhetorical appeal to the crowd, but soon realizes its futility — “I had no words and no eloquence.” He is shocked, at long last, into awareness. With Ras calling for his death, the narrator finds his hands on the spear. Reality and symbolism collapse upon one another. The narrator lets the spear fly and he watches it rip through Ras’s cheeks, locking his jaws. Ras wrestles with the spear as the narrator flees the uncanny scene.

All of this, however, would be too tidy a resolution — the hero vanquishing his antagonist, claiming his own identity as an invisible man — for a book as defiant as this. Just as the novel’s focus closes in on the protagonist, Ellison expands the frame. Still wandering the streets, the narrator overhears a conversation among a small group of Black men; unnoticed, he stays to listen. Over the next several pages, the men pass a bottle back and forth as they talk and shout and laugh about Ras and the riot, conjuring tall tales out of tragic circumstances. Some of the lines read like the source material for Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor stand-up riffs: the Black Everyman as wry observer of the foibles both of white folks and his own folks. “I was drinking me some Budweiser and digging the doings,” one of these down-home rants begins, “when here comes the cops up the street, riding like cowboys, man; and when ole Ras-the-what’s-his-name sees ’em he lets out a roar like a lion and rears way back and starts shooting spurs into that hoss’s ass fast as nickels falling in the subway at going-home time — and gaawd-dam! that’s when you ought to seen him! Say, gimme a taste there, fella.” With chaos, even death, around the corner, these men are somehow still at ease. As readers, it puts us at ease, too, the humor helping metabolize the surreal scene that precedes it by bringing it within the command of the tragicomic eloquence of these street-corner chroniclers. It baffles the protagonist. “Why did they make it seem funny, only funny?” he wonders.

IT TOOK ME UNTIL 2021, on perhaps my 40th time through the book, to give this passage the attention it deserves. Opening my tattered copy of “Invisible Man,” the same one I carried with me up those manor house steps more than half my life ago, my notes appear as palimpsest: layers of thinking and rethinking, circles and underlines, question marks and exclamation points written in a riot of pencil and ink. But I left these pages in the book blank, whether out of puzzlement or neglect. Reading them today, I realize that I now see myself in Ellison more than in his protagonist.

In these pages Ellison understands — I think I do, too — something that his protagonist does not: that these men are exercising their tragicomic awareness of life, a capacity to contain chaos and not to fall victim to nihilism. Their laughter is necessary equipment for living while Black in America, something the narrator will have to write his memoir to learn — something that Ellison himself had to learn. In a long-labored-upon essay titled “An Extravagance of Laughter,” published in “Going to the Territory,” Ellison recalls his own experience confronting Jim Crow racism as a college student in Alabama during the 1930s. “My problem,” he writes, “was that I couldn’t completely dismiss such experiences with laughter. I brooded and tried to make sense of it beyond that provided by our ancestral wisdom.”

“Invisible Man” demands to be read, then, not solely as an indictment of white supremacy’s obliterating gaze, but as a tall tale that dilates our frame of reality to entertain us, and by entertaining us perhaps to save us. During a 1955 interview with The Paris Review, Ellison responded with exasperation at his interviewers’ self-serious line of questioning about his novel. “Look,” he finally asks, “didn’t you find the book at all funny?” When questioned by those same interviewers about whether his novel would still be read in 20 years, Ellison was dubious. “It’s not an important novel … many of the immediate issues are rapidly fading away.”

Behind this humility is a remarkable claim. Ellison believed — as someone who grew up in segregation perhaps he had to believe — that the conditions his novel exposes (racial discrimination, the erasure of Black identity, the failings of American democracy) might soon improve to the point that the book would no longer resonate. Almost 70 years after his novel’s publication and nearly 30 years after his death, we now know what Ellison could not: that many of the conditions he described have not only persisted but propagated. This fact, along with Ellison’s timeless talent, is why the novel endures. Its power lies in how it confronts racism and white supremacy with a realism that dilates to contain the surreal nature of American life. It lies in its blues-toned understanding of how people endure and even make beauty out of brutal experience by, as Ellison elsewhere describes it, choosing “to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.” This is the challenge that “Invisible Man” sets out. And it is this which frightens me: Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, it speaks for us?