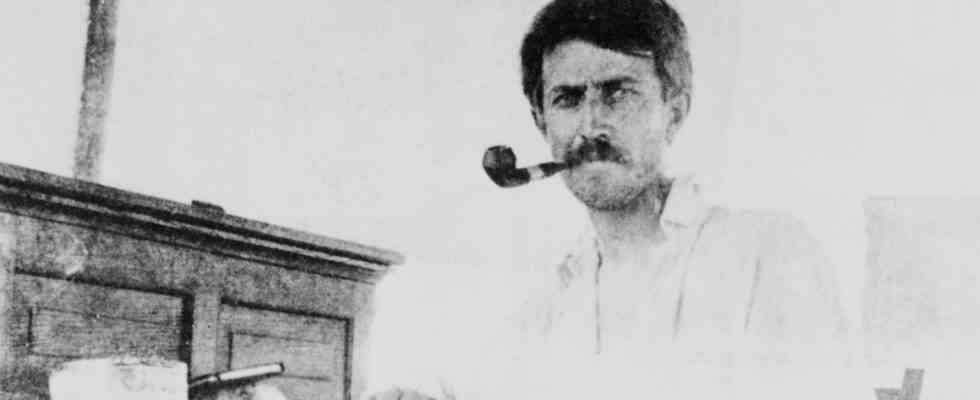

Stephen Crane became famous with the publication of The Red Badge of Courage in September 1895, when he was 24 years old; for the rest of his short life, he would—somewhat to his chagrin—be known as “the author of Red Badge.” Less a novel than a dreamlike meditation on practical versus theoretical knowledge, it argues for the former with a command, and a disillusion, belying the fact of its author’s birth six years after the end of the war it depicts. As such, it points to a fundamental ambiguity in Crane’s writing and career, in which reports on experience preceded experience itself, prompting the writer’s ardent efforts to live up to his own authority. His life repeated the path of his protagonist. His dreams became real, then became nightmares.

Born to a distinguished Methodist family in Newark, N.J., in 1871, the youngest of nine surviving children, Crane lived after his father’s death in 1880 with a succession of siblings, eventually settling in the seaside resort town of Asbury Park, where an older brother edited a local newspaper and managed branch offices for the New-York Tribune and the Associated Press. Reporting on summer life in Asbury Park for his brother’s paper gave him his first taste of professional journalism, and after two abortive stints in college, he resolved to become a writer. Undeterred when national political controversy surrounding one of his columns got both brothers fired, Crane moved to Manhattan, where he began exploring the working-class immigrant neighborhood known as the Bowery. From these experiences, and the imagining they prompted, came his first novella, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, which he self-published in early 1893, and which found an eminent, if not a wide, readership.

The next two years were decisive. An abridged version of The Red Badge of Courage: An Episode of the American Civil War appeared in newspapers in December 1894. After Crane’s return from reporting on the West and Mexico, The Black Riders and Other Lines—he refused to call them “poems”—was published in May 1895 to much notoriety, as much for its sibylline style as for its “anarchy,” which alternated between denying and rebuking God. But it was the book publication of Red Badge that fall that secured his name—particularly once critics in England hailed the work as a masterpiece, equal to or perhaps surpassing Zola and Tolstoy in its immersive portrayal of war. Crane’s fame was transatlantic from the first; he would later spend substantial time in England, ultimately dying in Germany, where he had gone in a last, knowingly doomed effort to recover from an array of illnesses and exhaustion. He was 28. By that point he had lived, and written, enough for several lifetimes.

The known facts of Crane’s life have largely been established by previous scholars. In his new biography, Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane, the novelist Paul Auster records the main events and traits, but his emphasis falls on the work. Like the poet John Berryman, whose 1950 Critical Biography renewed a precedent, established during Crane’s lifetime, for appreciation by fellow writers, Auster writes as his subject’s champion. (Whatever the merits of such defenses as a genre, when an author continues to prompt them, it is generally a good sign—of something disturbing, unassimilable, undeniable.) Yet where Berryman wrote against the irresolution of critics, Auster faces the more difficult problem of what he perceives to be neglect among readers. To defend Crane, he must reintroduce him. This he does assiduously and at length, showing that Red Badge, Crane’s “masterpiece,” represents only a sliver of a vast and varied body of writing that includes “close to three dozen stories of unimpeachable brilliance” and “more than two hundred pieces of journalism, many of them so good that they stand on equal footing with his literary work.”

And yet what Auster calls Crane’s “many-ness” can just as well be seen as the refractions of a remarkably consistent set of conceptions. Does one see oneself as small or as gigantic against a bare landscape? Crane’s writing thrills to both intuitions, but especially the former, which finds echoes in the feeling of being immersed in city crowds and in the large and small acts of organized violence that fascinated him. The characteristic images of his poetry are of solitary men on mountains and masses crossing vacant plains; his characteristic man is a demon who howls. He was, as Auster observes of Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, “reluctant to assign names to his characters.” His tales pick them up and put them down like playthings; our identifications are constantly tested by abrupt shifts in perspective that mimic the disproportions of nature and reveal the fundamental disproportion of every individual vantage point. What earlier critics called Crane’s “naturalism” can be seen, in part, as the tracing of such fatality in the Gilded Age society in which he lived, in which (as he wrote) “pocketbooks differentiate as do the distances between stars.”

Tempting though it is to call Crane a descriptive writer—with his fitful characterization and experience filing reports and sketches for the Hearst and Pulitzer syndicates—it is more accurate to say he explores where the boundary between description and psychology breaks down. His interest is in the dynamics of situations—intersubjective, emergent under conditions of extreme duress—in which one’s identity and characteristics become secondary or at least unpredictable in their bearing. An early conviction that the opportunities for meaningful experience were over (a childhood plan to become a soldier was abandoned when an older brother convinced him no wars were likely during his lifetime) gave way to exploration of the empires, economic and otherwise, then swelling toward their apex. If their extent exceeded sensory apprehension, he elaborated, as if in compensation, a literature of pure immediacy: one that excluded not just ideals and ideas but also his characters’ prior histories, their larger purposes, even their names.

What struck him were not programs but contrasts. The excised portions of a report on a Scranton coal mine tell of “the impersonal and hence conscienceless thing, the company” and recount how a set of visiting coal brokers, trapped underground with their miners, almost perished in a common fate—an episode in which Crane confessed he saw, with “dark and sinful glee,” the prospect of “a partial and obscure vengeance.” Hypocrisy likewise stirred his social instincts, and joined them to a writerly sense of honor. Incendiary though many of Crane’s early writings were, however, none affected his career as much as when he took the stand in support of Dora Clark’s suit against the New York Police Department, after one of its officers arrested her on a false charge of soliciting. Neither the truth of Crane’s testimony nor his acquaintance with then–New York City Police Commissioner Teddy Roosevelt protected him. His personal life was ransacked and exposed; witnesses collapsed under intimidation, or simply perjured themselves. Though he was left with “a clear conscience,” persistent police harassment meant Crane would never report from New York City again. Everything afterward, in Auster’s telling, would be his period of “exile.”

Soon came disaster. Sent to report on the illegal “filibustering” operations that ran guns from Florida to Cuban insurgents against the Spanish imperial government, Crane finally set sail from Jacksonville after many delays on New Year’s Eve, 1896. The next night, his ship, laden with guns and ammunition and ferrying a company of Cuban exiles, sank in a heavy storm. Crane recorded the sinking, including a futile, partly abandoned effort to save seven men stranded on the foundering Commodore, in a newspaper account published four days after the event. A few months later, his story “The Open Boat” told the rest of what had happened: how Crane and three other men—one of them, the captain, disabled with a broken arm—spent 30 hours in a 10-foot boat, trading off rowing through extreme exhaustion until they were finally able to swim for land, only to have Crane’s rowing partner wash ashore dead. A strong swimmer, he had, one of the papers reported, been struck on the head when their boat overturned in the waves piling up on the shore.

“It was,” Auster contends, “the most important experience of his life,” and it would haunt him to the end. The next April, when he dedicated The Open Boat and Other Stories (1898) “To the Late William Higgins” and the two other survivors of their ordeal, he acknowledged, imperfectly, his writing’s cost. By that point, further losses had accumulated, and they would continue to do so. “The Open Boat” had been subtitled “A tale intended to be after the fact,” yet one fact continued to elude Crane. With events stalling in Cuba, where fighting seemed reluctant to break out, he found himself, four months after the sinking of the Commodore, across the world covering Greece’s war with Turkey over the sovereignty of Crete. With him was Cora Taylor, whom he had met the previous year in Jacksonville, and who now traveled as his wife and filed her own war dispatches as “Imogene Carter.” When he and Cora traveled thereafter to England, it was with memories full of the horrors they had witnessed from afar and up close. He wrote them down, along with some of his strongest American stories, while living amid the toniest of literary circles, centered in Sussex, and he also began an intense literary friendship with Joseph Conrad, some 14 years his senior, then little-known and struggling. Life in Sussex was in many respects idyllic. Soon enough, though, Crane was back on a ship across the Atlantic, headed for Florida—and Cuba.

The Spanish-American War was notoriously a newspaper war; yet Crane, though sympathetic to the Cuban rebels, was not among its propagandists. To a degree his reports from the fighting are continuous with his early Maggie, whose achievement, for Auster, was to have created “a literature of pure telling, with no social analysis, no calls for reform, and no psychological reflections to explain why the characters do what they do.” In other respects, they recalled his reporting from Scranton, notably in his complaint that the black-gunpowder charges issued to the US soldiers produced smoke that disclosed their positions, unlike the modern smokeless powder used by the Spanish. Later stories, blending reportage and fiction, chastised the use of the war to burnish the careers of aspiring politicians and how it cast newspapermen in the role of theater impresarios, “obliged to keep the curtain up all the time.” For Crane himself, Cuba drew back a veil: not of illusion (he had none) but of curiosity, of all but the final distance between his imaginings and “the deadly range and oversweep of the modern rifle, of which many proud and confident nations know nothing save that they have killed savages with it, which is the least of all informations.” Crane’s anti-imperial barb carried an undercurrent of masochism in its implication that one would have to be shot to know. It was a knowledge he struck several observers as overly bent on acquiring.

Auster is doubtless correct in his overall judgment that Crane “did not have the impulses of a reformer” and “took little or no active interest in politics.” This does not prevent him from searching Crane’s work for creditable impulses—typically, toward a moderate solidaristic liberalism that happens to resemble the critic’s own. Such efforts do not lack evidence, but obscure genuine tensions. For one thing, there is Crane’s refusal of envy and pity; but this would be less at issue if it clearly stemmed from individualism (portrayed by Auster as a concern with the self that can be broadened), instead of a certain aloofness, from himself as much as from others. Auster’s efforts at distinguishing, in Crane, between “an active spirit of cooperation” and “a passive unity among disconnected individuals” as good and bad forms of collective action are suitably hedged but likewise questionable, for it is just such distinctions that Crane’s interest in circumstance tends to blur. The idea that the right kind of action, or even the right aim, reliably produces good results runs counter to his deepest fascination with fate and risk.

Earlier critics have probed the origins of these fascinations—Berryman, notoriously, in a byzantine essay in applied psychoanalysis that found Crane’s portrayals of racialized males (Africans and Swedes) encoded a “primal scene” connecting violence and sexuality. On the whole, Auster’s aims are appreciative rather than interpretive; as such, they can be compared to Crane’s own: “I bring this to you merely as an effect—an effect of mental light and shade, if you like; something done in thought similar to what the French Impressionists do in color; something meaningless and at the same time overwhelming, crushing, monstrous.” Unfortunately, where Crane is pithy and intense, his appreciator is too often diffuse. To an extent, this is compelled by the density of Crane’s effects and their dependence on context, both of which demand unfolding. On Crane’s style, Auster is perceptive; his dissections of the multilayered self-delusion of Crane’s characters would be hard to improve on. And yet too many lengthy summaries weigh down his account. Appreciation often works best by evocation and selection. In this as in other respects, one may find oneself missing Berryman’s abruptness—as well as his stronger sense that there is in Crane something profound and destructive that is not to be accounted for solely in terms of the spirit of the times.

From his earliest writing, Crane believed that to know means experiencing firsthand; yet fully experiencing seems to involve some surrender of the capacity to know. Several of his best tales depict climactic events of such suddenness that they are, so to speak, only experienced in the moment of being recalled. In this, he stood at variance with what might seem a kindred ethos of the era of imperial expansion, which, as Michael Fried (another of his champions) has observed, tended to entice its “younger representatives” by casting them “in the passive role of blank surfaces on which their experiences…would inscribe the first identity-defining marks.” But Crane’s project cannot be understood in any ordinary sense as one of self-making. He remains, like his characters, something of a cipher: an accumulation of shocks who transmitted and then was destroyed by them. What stood fast were his sentences, reckless and unalterable.