Sixty years ago this spring, there was a huge — literally — shift in women’s bodies. For such a fundamental change, it happened almost by accident.

Timmie Jean Lindsey, a 29-year-old mother of six, went into hospital in Houston, Texas, for a routine operation to remove a tattoo from her breast.

Her two surgeons, Frank Gerow and Thomas Cronin, persuaded her to undergo a new procedure, which until then had only been tested on dogs: breast implants. She went from a B to a C cup.

Some, such as Victoria Beckham (pictured in 2006), had augmentation surreptitiously, only admitting it when she later removed her implants

It was curious timing, given the procedure took place within weeks of another memorable occasion in the history of womankind — May 19, 1962, when the world was given an eyeful of a woman deemed the pinnacle of female beauty, whose breasts were all her own.

Marilyn Monroe sang happy birthday to President Kennedy in a near-transparent cobweb dress that exposed her bra-less embonpoint.

She was the envy of every woman in the world, desired by every man.

Her breasts were natural. They were bountiful. They hung, as they should, creating an almost triangular outline that, if it were the hands on a clock, would be telling the time at precisely 20 minutes to four.

But as an ideal they were soon, because of a scalpel wielded 1,500 miles away, to become extinct. An outline to be ashamed of, altered, excised, deemed not good enough.

Reflecting on the consequences of her procedure, Timmie said some ten years ago: ‘I was not wise enough to realise the magnitude of it.’

The 1960s are remembered as the decade when women were released from so many shackles. Unwanted pregnancy, thanks to the Pill.

Backstreet abortions, thanks to legalisation. Giving up work after having children. The expectation of marrying young.

Kourtney Kardashian (pictured in 2007) recently said of her breast operation: ‘I had my boobs done but if I could go back, I wouldn’t have done it’

But breast augmentation was waiting in the wings to spread as rapidly as a stain on a shirt when someone has been stabbed in the chest. Which, in a way, we have.

It is the modern-day equivalent of foot binding — mutilation of the female body to fit an unrealistic beauty ideal.

Because for all those adverts that litter the internet and glossy magazines, which fool women into believing cosmetic surgery is easy, as simple and thoughtless an act as dyeing your hair, the reality is so very different.

It’s an operation from which it takes weeks to recover and it carries risks galore — not to mention the fact that those implants will likely need replacing after a decade or two.

It’s not only a physical mutilation, but a mental one, convincing you that your breasts, those implicit symbols of femininity, can somehow be deficient. That a surgeon’s knife is the only thing that can ‘fix’ you.

That high, hard, perky breasts are somehow more desirable than your soft, natural female form.

Millions of women have had breast implants since Timmie went under the knife.

The most popular form of cosmetic surgery in the world, in the UK alone some 7,000 women a year have their breasts altered.

(Perhaps one of the few benefits of the pandemic is that the number of cosmetic procedures in 2020/2021 saw the largest drop for 18 years.)

Even after the scandal of 2010 — when it was revealed that the French company PIP made implants using industrial-grade silicone, which led to illness and even death — we were not to be deterred.

The boom began in the 1990s when, leading the charge, of course, were celebrities, whose breasts began to enter rooms several seconds before their owners did.

We all know these stars’ names, as they’re famous for their cleavages: Pamela Anderson is said to have had breast augmentation surgery in 1990, while Katie Price had the first of what she claims are 24 procedures when she was just 18.

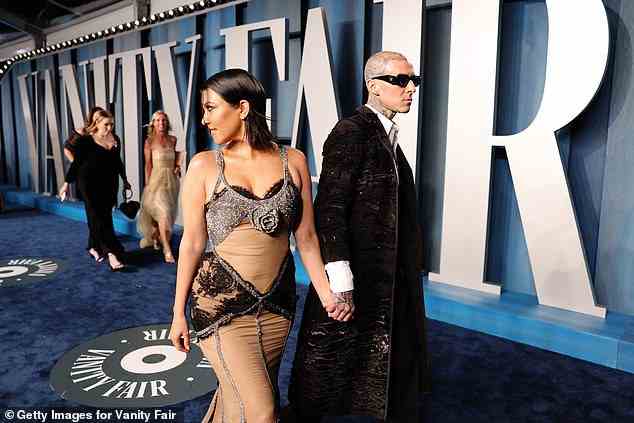

Kourtney Kardashian and Travis Barker attend the 2022 Vanity Fair Oscar Party. Kourtney Kardashian recently said recently she wouldn’t have a breast operation if she ‘could go back’

Others, such as Victoria Beckham, had augmentation surreptitiously, only admitting it when she later removed her implants, saying: ‘All those years I denied it — stupid. A sign of insecurity. Just celebrate what you’ve got.’

Although the numbers of British women going under the knife in pursuit of a bigger bosom are falling — figures show that just under 8,000 women had breast augmentation in 2018, down 6 per cent from the previous year — the so-called Love Island effect, which sees young women convinced they need to conform to a specific pneumatic template in order to be considered desirable, is far from over.

Take Faye Winter, a contestant on the most recent series of the image-obsessed reality show, who revealed she was so badly bullied at school for being flat-chested her parents bought her implants for her 18th birthday. It’s her sort of story that sets alarm bells ringing.

Because I’m mostly concerned with the ordinary women who have gone under the knife in those six decades, never destined to make the cover of a magazine.

To carry out some informal research, I went to a town centre near where I live in the north of England this week to ask young women about breast implants.

They’re so endemic it wasn’t hard to find those who had undergone breast augmentation.

While surgery can cost around £8,000, still a significant sum, those who’d had it weren’t high-earners — a shop assistant, a hairdresser, someone out of work, and a student (no doubt they obtained the money on a ‘boob job’ payment plan — yes, today there are even finance options for your breasts).

Of course, when quizzed as to what made them do it, they all said it was their ‘choice’. That it ’empowers’ them. That their new breasts make them feel more confident.

Katie Price, pictured in 2012, had the first of what she claims are 24 procedures when she was just 18

‘My boyfriend likes them,’ said one. ‘I want to wear low-cut dresses,’ said another.

‘I was teased for being flat-chested,’ admitted one girl.

‘I hated being a pear shape,’ confessed another.

They may think they’re being honest, but most impressionable young women without a protective bubble — interfering parents, eagle-eyed teachers — are surprisingly easy to brainwash.

I know this from my own experience.

In 1987, it took just one headline in Elle magazine — ‘Women in France are having breast reductions to look better in jackets’ — alongside a photograph of an elegant and unbusty Yasmin Le Bon, to make me book a breast reduction operation, aged 29.

I was ashamed of my breasts — too ashamed even to measure them, but I would say they were around a DD cup.

Because of steroids prescribed to tackle the anorexia I had suffered from for most of my life, my breasts had grown pendulous, almost reaching my waist.

I told no one. I lived with my sister, and even she had no idea. My operation was a compulsion. I thought it would make me happy.

I know from my own experience that women can see a breast operation — and other procedures — as not merely cosmetic, but life-saving.

And, yes, big breasts can be physically debilitating, causing neck and back pain and restricting ability to exercise.

But women, myself included, convince themselves that breast surgery is a psychological panacea, nothing short of vital for our happiness.

We are not vain — just desperate — and easily seduced by the consumer culture that has marketed expensive life-changing surgery as a ‘quick fix’ to cure all.

Faye Winter, a contestant on the most recent series of Love Island, revealed she was so badly bullied at school for being flat-chested her parents bought her implants for her 18th birthday

There is an advert for surgery on the London Tube at the moment urging women to ‘Make yourself amazing!’

Wouldn’t it be great if we thought, ‘I’m already amazing, thanks.’

Indeed, women who have had their breasts altered speak of the intoxicating ‘high’ they get afterwards, the feeling that they have marshalled their recalcitrant bodies into obedience.

Those young women I spoke to really believed being sliced open rendered them more in control.

I felt this too — and truly believed I couldn’t go on if my breasts weren’t reduced to an acceptable shape.

We are bombarded with perfect images to aspire to that convince us we don’t want to live unless we are beautiful. But notions of beauty change, as they have throughout history.

As flat-chested me, I felt vaguely happy for a while, despite the scars and puckering. Until fashion changed.

A seismic moment came when, as the editor of Marie Claire magazine, I went backstage at a Dior fashion show, at the end of the 1990s, to hug the new body of the moment, a Brazilian supermodel.

It was like embracing a sparrow, other than her two perfect, round, high breasts. Here was the new shape, one not remotely possible in nature.

By the end of this decade, boobs were no longer considered something cheap. They were cool.

By 2004, even that most fashionable and powerful of creatures, Sex And The City’s Samantha Jones, wanted bigger boobs as hers were, she said, ‘teeny tiny’. Fake boobs were officially the new normal.

Because breasts, it seemed, were now at the whim of fashion trends, as much as hemlines used to be. One minute we’re expected to have a streamlined elfin body; the next, breasts that hover just below our chins.

I might have been a glossy magazine editor when I hugged that supermodel, but I didn’t want young women to mutilate themselves as I had.

At the back of the magazine we published numerous adverts for plastic surgery. I tried to get them banned, but they were deemed too lucrative.

These days, women browse websites of cosmetic surgery companies as if browsing properties on Rightmove, dreaming not just of a new house, but a new body.

But breasts shouldn’t be bought like a new It-bag. Nor is there any sane reason why they should be the subject of so much insecurity.

‘By 2004, even that most fashionable and powerful of creatures, Sex And The City’s Samantha Jones, wanted bigger boobs,’ Liz Jones writes

It’s as though these fake breasts are an apology for all the things women no longer are: compliant, stay-at-home mums, martyrs, patient, forgiving. An attempt to fulfil what we imagine the male ideal is, in an all-too visible way.

We’ve lost so many other signals of traditional femininity, perhaps it’s no surprise we’re desperately pumping up our cleavage.

But what’s the solution? How do we get the message across to the next generation of young women that they are good enough as they are?

No one spotted I was at risk, that I hated my own body. I refused to use the communal shower at school, always made an excuse to get out of swimming, but no one took me aside to ask why.

When I went for my breast op, I wasn’t made to see a counsellor first. I was simply waved through.

Far more effective would be to hear from more celebrity women such as Kourtney Kardashian, who said recently of her breast operation: ‘I had my boobs done but if I could go back, I wouldn’t have done it.’

We need to see more real breasts: all shapes, sizes, colours, ages. Perhaps a kite mark on every photo to denote the breasts are as God made them? Because why should women conform to an edict dreamt up by two men 60 years ago?

There is no one-size-fits-all. And the sooner women embrace that realisation, the happier we will all be.