Pat Robertson, a Baptist minister with a passion for politics who marshaled Christian conservatives into a powerful constituency that helped Republicans capture both houses of Congress in 1994, died on Thursday at his home in Virginia Beach, Va. He was 93.

His death was announced by the Christian Broadcasting Network, which Mr. Robertson founded in 1960.

Mr. Robertson built an entrepreneurial empire based on his Christian faith, encompassing a university, a law school, a cable channel with broad reach, and more. A product of a family with politics in its veins, he also waged a serious though unsuccessful campaign for the 1988 Republican presidential nomination, resigning as a Baptist minister as he began the run in the face of criticism about mixing church and state.

The loss did not dampen his political fervor; he went on to found the Christian Coalition, which stoked the conservative faith-based political resurgence of the 1990s and beyond.

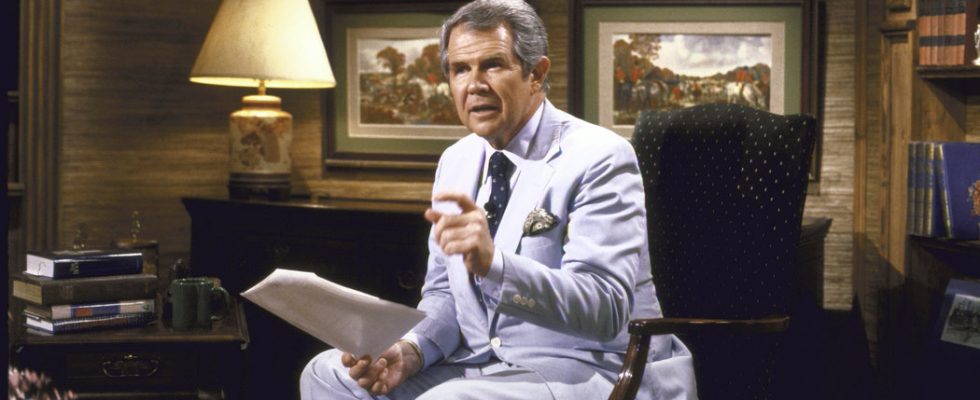

Whether in the pulpit, on the stump or in front of a television camera, Mr. Robertson could exhibit the mild manner of a friendly local minister, chuckling softly and displaying an almost perpetual twinkle in his eye. But he was also given to statements that his detractors saw as outlandishly wrongheaded and dangerously incendiary.

He suggested, for example, that Americans’ sinfulness had brought on the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks against the United States, and that the earthquake that devastated Haiti in 2010 was divine retribution for a promise that Haitians had made to serve the Devil in return for his help in securing the country’s independence from France in 1804.

He said that liberal Protestants embodied “the spirit of the Antichrist” and that feminism drove women to witchcraft. He called for the assassination of President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela. He maintained that his prayers had averted hurricanes. And he condemned homosexuality as “an abomination,” linking it at one point it to the rise of Hitler and declaring that it provokes God’s wrath, as manifested in natural disasters and even the death and destruction of 9/11.

In December 2020, amid intensifying efforts by President Donald J. Trump and his supporters to overturn the election, Mr. Robertson told viewers of his television show, “The 700 Club,” that a lawsuit filed by the Texas attorney general challenging results in four states was a “miracle.”

“They’re going to the Supreme Court to say, ‘This election was rigged and you’ve got to overturn it,’” Mr. Robertson said, citing unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud. He declared that “God himself” would intervene.

Barely two weeks later, he changed course. “The president still lives in an alternate reality,” he said, adding: “I think it would be well to say, ‘You’ve had your day and it’s time to move on.’”

David John Marley, the author of “Pat Robertson: An American Life” (2007), said that Mr. Robertson’s statements were calculated to arouse his core following: Christians who felt ignored or mistreated by elites.

“The more he is publicly vilified, the more his minority-under-attack thesis appears to be true,” Mr. Marley wrote.

It had become a potent constituency. In 1986, Ed Rollins, who managed President Ronald Reagan’s 1984 re-election campaign, said Mr. Robertson had “more assets than the Republican National Committee.”

In his presidential campaign, in 1988, Mr. Robertson finished a strong second in the Iowa caucuses, but later dropped out of the race when it became clear that George Bush would clinch the nomination.

Mr. Robertson’s Christian Coalition reached the peak of its influence in 1994, when it helped to elect the first Republican Congress in decades. It had a budget of around $25 million and a membership of four million or more.

Many thought politics was Mr. Robertson’s natural home, though few doubted the sincerity of his religious practice, which included speaking in tongues and faith healing.

His father was Absalom Willis Robertson, a Democratic United States congressman and senator from Virginia for 34 years who fiercely defended the conservative agenda of his day, including segregation and opposition to the New Deal.

Garrett Epps, an author and legal scholar, wrote in The Washington Post in 1986 that political analysts “treat Pat as if he came from Mars, rather than finding antecedents of many positions in the political stands his father took a generation ago.”

Preachers and Politics

Marion Gordon Robertson was born on March 22, 1930, in Lexington, Va., to parents who were first cousins and the offspring of Baptist preachers. His youth was shaped by his proximity to Washington policymakers, and by his father’s insistence that he learn the value of work and responsibility through backbreaking farm labor.

His mother, the former Gladys Churchill Willis, imbued him with religious faith, and with a sense of pride in a genealogy that included two presidents (William Henry Harrison and Benjamin Harrison). She told him God had a plan for him.

He was called Pat because, when he was a baby, his older brother and only sibling, A. Willis Robertson Jr., had patted him on his cheeks, saying, “Pat, pat, pat.”

Pat attended the McCallie School, at the time a military prep school, in Chattanooga, Tenn., and graduated from Washington and Lee University in Virginia. He spent a year at the University of London, then joined the Marines. He avoided combat in Korea, which some attributed to the influence of his senator father.

He went to Yale Law School, where he met a nursing student, Adelia Elmer, known as Dede. They secretly married on Aug. 27, 1954, and their first son, Timothy, was born 10 weeks later. For years the couple said that their wedding date was March 22, 1954. Reporters discovered the Robertsons’ marriage certificate in late 1987, after Mr. Robertson had announced his candidacy for the presidency.

“I have never, ever indicated that in the early part of my life I didn’t sow some wild oats,” he told reporters. “I sowed plenty of them. But I also said that Jesus Christ came into my life, changed my life and forgave me.”

Adelia Robertson died in 2022.

Mr. Robertson graduated from Yale, but did not pass the New York State bar examination. He worked as a trainee for W.R. Grace & Company, then as a partner in an audio components firm. A Democrat at the time, he was chairman of the Adlai Stevenson for President Committee on Staten Island, where he lived, in 1956. He wrote that during this period he developed a taste for the “upholstered sewers called nightclubs” and gambled recklessly.

It didn’t make him happy. He felt empty, and he considered suicide. An encounter with an evangelist led him to become a committed Christian. He wrote in his autobiography that he took down a painting of a nude over his sofa and poured out his bottle of Courvoisier. He left his pregnant wife and child to attend a Christian camp in Canada for a month. “God will take care of you,” he told her.

Back home in New York, he worked briefly at a nonpaying job at a religious magazine before entering the New York Theological Seminary (called the Biblical Seminary in New York at the time), which taught biblical inerrancy. He earned a master’s degree in divinity in 1959 and was ordained as a minister in the Southern Baptist Convention in 1961.

He nonetheless worried that his religious conversion was incomplete. Then his son Timothy fell ill with a 105-degree fever. While praying for him, Mr. Robertson found himself speaking in tongues. He became a charismatic Christian.

His strengthened faith prompted him to sell his family’s furniture and other belongings, and give the proceeds to Korean orphans. He did this while his wife and children were visiting her family in Ohio. She was furious. Years later, she offered advice to women in similar situations: “God can be your husband,” she said.

Birth of a Network

Mr. Robertson moved the family into a rat-infested brownstone parsonage next to a brothel in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. He was a minister to that community when his mother told him that a small, decrepit, off-the-air UHF television station in Portsmouth, Va., was for sale. By his account, he spoke to God, who advised him to offer $37,000, much less than the $300,000 the seller wanted.

His bid was ultimately accepted, and Mr. Robertson gathered cash from family and friends to start in 1960 what he boldly called the Christian Broadcasting Network.

It went on the air on Oct. 1, 1961, as WYAH-TV, a name taken from the Hebrew word for God, Yahweh. An early fund-raising drive involved asking 700 people to pledge $10 a month each, a lot for the time and place. His request was fulfilled. In 1966, that success gave birth to “The 700 Club,” which became Mr. Robertson’s signature program. The network soon had a game show and a daytime drama, “Another Life,” which the station promoted as “the soap with hope.”

Mr. Robertson avoided the fire-and-brimstone approach of television preachers like Jimmy Swaggart and the shoot-from-the hip ways of Jerry Falwell. He did a couple of PBS-style telethons a year, rather than constantly asking for money.

“Television is a mass communications vehicle,” Mr. Robertson said in a 1995 interview with CNN. “It’s not a church service.”

Mr. Robertson became one of the first broadcasters to syndicate shows nationally, and one of the first to use satellite transmission, and he started one of the first basic cable networks of any sort.

He was one of the first evangelists to seek commercial sponsors and to use toll-free numbers for prayers and contributions. He was the first religious broadcaster to have a Washington newsroom. He did local broadcasts in foreign countries.

Eventually his broadcasts would be seen in 200 countries and heard in 70 languages, collecting hundreds of millions of dollars in donations and redefining Christian broadcasting by serving up religion as news and entertainment.

His big corporate success was establishing CBN as a satellite network in 1977, and adding secular shows to its programs, mainly reruns of popular family shows like “Flipper” and “Father Knows Best.” In 1988, it was renamed the CBN Family Channel to attract advertisers uneasy with overt religion. After the tax authorities questioned its religious exemption, Mr. Robertson split it into for-profit and nonprofit entities.

Sale Price: $1.9 Billion

In 1997, Mr. Robertson sold the Family Channel to Fox Kids Worldwide, headed by Rupert Murdoch, for $1.9 billion. Fox sold it for $5.3 billion in 2001 to Disney, which rebranded it ABC Family and, later, Freeform. Mr. Robertson retained the right to show “The 700 Club” in perpetuity three times a day on the network. Television Week in 2005 called this deal “a perpetual money machine.”

Money from the original sale went into a trust used to help finance the CBN broadcasting complex; Regent University, the religious school Mr. Robertson opened as CBN University in Virginia Beach, Va., in 1978; Operation Blessing, a worldwide charity; and the American Center for Law and Justice, a nonprofit Christian legal advocacy group.

Mr. Robertson dealt with many controversies, including his highly publicized break with two of his most popular broadcasters, Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker. (Years later, when Mr. Bakker was embroiled in scandal, Mr. Robertson condemned him.) He was criticized for joining African dictators in mining ventures. He was attacked by other evangelicals for remaining silent on China’s promotion of abortion while he was negotiating to set up a network there.

Conservatives were appalled when he appeared with the Rev. Al Sharpton in a commercial warning of global warming in 2008. In fact, many evangelicals felt that an evangelist — a term Mr. Robertson rejected in favor of “broadcaster” — had no business in politics in the first place.

But at the time of Watergate, he felt he could not remain silent and called for President Richard M. Nixon to repent.

Mr. Robertson is survived by his two sons, Timothy and Gordon; two daughters, Elizabeth Robertson Robinson and Ann Robertson LeBlanc; 14 grandchildren; and 24 great-grandchildren.

In 2007, Mr. Robertson passed management of CBN to his son Gordon. In 2011, he said he would no longer endorse candidates.

In October 2021, at the age of 91, he announced that he was stepping down as host of the “The 700 Club” after more than 50 years at the helm. “It’s been a great run,” Mr. Robertson said on the show, adding that his son Gordon Robertson would take over as host.

But he never stopped talking politics — and his flock never stopped listening. In 2001, Michael Lind, an author on political topics, wrote in The New York Times that Mr. Robertson had been “the most influential figure in American politics in the last decade.”