“I was coughing hysterically,” Dennis Oya told me by phone from Coyote Ridge Correctional Center in eastern Washington State. “My chest kept ripping. I fractured my ribs—ribs four, five, and six—from cough compression.” In the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic, Washington’s largest tuberculosis outbreak in decades includes at least 25 cases of active disease connected to the state’s sprawling prison system. More than 250 other prisoners were also infected and have latent TB, which can escalate to active disease at any time. Oya, 42, considers himself patient zero. “The TB outbreak started because of me,” he said.

Oya noticed a suspicious cough in late 2019, when he was at Clallam Bay Corrections Center, near the northwestern tip of the Olympic Peninsula. “Every time I called home, you could hear me coughing. I couldn’t get full 20-minute conversations with my family, because of shortness of breath.” (Calls from prison go through private security companies, which charge hefty fees and cut them off after 20 minutes.) Oya remembers the date because in those terrifying early days of the pandemic, before cities in the US began social distancing measures, a postcard arrived from a pen pal in Hong Kong. “I remember my friends saying, ‘Oh man, that card had Covid, that’s why you’re coughing like that.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, no, it’s not.’ You can’t get sick from having a postcard, you know what I mean?”

Oya tested negative for Covid, but he kept coughing. Medical staff told him his cough was caused by allergies, then diagnosed him with a hiatal hernia (a common cause of acid reflux, which can trigger a cough). He took his hernia prescriptions carefully, lost weight as he was instructed to do—and still kept coughing violently.

Oya had been diagnosed with TB when he was 18, and he was certain the disease had returned. Every year on their birthday, incarcerated people are supposed to be offered a test for latent TB. Oya knew he would test positive—a positive test for TB remains positive for life. Oya’s doctor, the medical director of the Puyallup Tribe, told him he should have been offered tests for active disease. “I was searching high and low. I’ve written grievances to try and get medical help,” Oya told me. “There are plenty of other people around me who were put in danger. Like my cousin—got tuberculosis. One of my other cellies: He got tuberculosis because of me.”

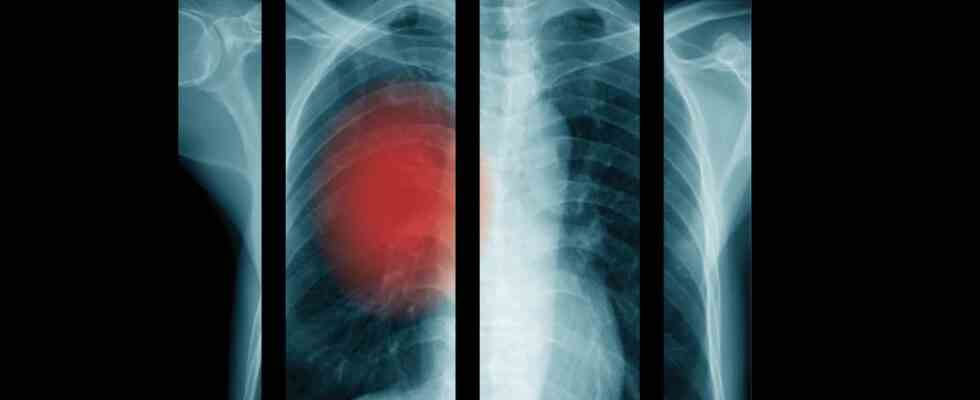

In May 2021, instead of being tested for active TB, Oya was transferred to Stafford Creek Corrections Center, a larger prison about three hours south. He was still coughing—and still hadn’t been given a TB diagnosis. On January 27, 2022, Oya was finally given a chest X-ray. That night, “they came to my door and said, ‘Roll your stuff up, you’re being sent out of here. You have TB, you got to leave.’”

In wealthy countries, tuberculosis is viewed as an antiquated disease. Yet in 2022, it regained its longtime status as the infectious disease that kills the most people around the world. (In 2020 and 2021, Covid-19 killed more people than TB.) The TB bacteria is transmitted through the air, and the disease persists wherever people are forced to share close quarters.

As an epidemiologist, I’m part of a team studying the TB epidemic in Brazil and Paraguay, countries where prison time comes with an almost 100-fold increase in the risk of contracting TB. But I was shocked when my sister, an organizer and the executive director of Real Change—a social justice organization in Seattle—sent me a press release from the group No New Washington Prisons about a TB outbreak. Rates of TB are relatively low in Washington, and it is thought that most TB in the United States is acquired abroad, in countries with higher rates of the disease.

Members of No New Washington Prisons put me in touch with the people who eventually put me in touch with Oya. We both knew our e-mails were being read—and our phone calls were being recorded—by prison authorities.

Untreated TB has a mortality rate of about 50 percent. But an early diagnosis—if it comes with access to antibiotics—can be lifesaving. Treatment also reduces the risk of transmitting the bacteria. Because of the heightened risk in the prison population, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the yearly testing of incarcerated people for latent TB, and that those with a history of positive TB tests—like Oya—be screened every year for symptoms of active disease.

According to the CDC, the risk of contracting TB is four times greater for a person incarcerated in a US prison than for someone who is not incarcerated. But the CDC’s guidance never mentions that the most effective way to prevent TB outbreaks in prisons doesn’t require biomedical interventions. As the prison scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore has noted, mass incarceration is relatively recent: A large proportion of prisons have been built and filled since the 1970s. In Washington, the prison population has nearly tripled since 1983; the jail population increased even more quickly. A system built so hastily is one that can also be dismantled quickly. A broad public health consensus has emerged that decarceration is the only way to prevent the outbreaks of deadly diseases perpetuated by our prisons.

By the time Andrew Lagerquist began to feel sick, he’d been transferred from Stafford Creek Corrections Center—where he was cellies with Oya for two and a half months—to Olympic Corrections Center, a minimum-security prison and work camp. One day at the gym, Lagerquist got a pounding headache. “My brain felt like it was about to explode,” he told me. He thought he might be adjusting to the wetter climate after his relocation, so he decided to ride it out over the weekend. Soon, he developed a fever and body aches. At night, he couldn’t sleep and was waking others in his unit. When he told prison staff he was having a medical emergency, “they gave me a Benadryl shot in my butt and sent me to the unit and told me I was dehydrated and needed to drink water.” A corrections officer came by and asked if he was feeling better. “They said, ‘Well, he’s probably just on drugs or coming down from drugs, so why don’t you give him a UA?’” (meaning a urine analysis test for drugs and alcohol).

The UA came back negative—but by then Lagerquist couldn’t stand up.

In December 2021, Lagerquist was finally sent to an emergency room, 26 miles north, where hospital staff collected samples for a battery of tests. The radiologist told him, “You have fluid in your lungs.” Lagerquist was diagnosed with pneumonia, prescribed antibiotics, and sent back to Olympic Corrections Center, where he remained on bed rest. He lost his appetite and his energy. “I started looking like a skeleton in my bed. I had to force myself to eat a bowl of oatmeal a day,” he told me. He lost 25 pounds. “I had to get up and walk to the bathroom and felt like I was going to pass out.”

When Omicron swept through the prison, Lagerquist, who had already had a bout of Covid-19, caught it a second time. Confined to the Covid quarantine pod, he knew his symptoms were worse than just Covid. He told the medical staff, “Listen, I feel something in my lung. It’s rattling in my lung…. You need to send me back to hospital.” (The ER doctors had requested that Lagerquist return for a follow-up after his first visit, but their request was ignored.)

When he was finally sent back to the ER, Lagerquist mentioned to a nurse that he’d been feeling slightly better in recent days. The nurse said, “Oh my God, are you sure you’re feeling better? Your X-rays show that almost half of your lung has fluid in it.” After another round of tests, the nurse told Lagerquist, “We found out what your problem is: You got tuberculosis.”

Lagerquist was diagnosed with pleural TB, a rare condition in the US, in which fluid builds up in the sac of tissue surrounding the lungs, often because the bacteria has lingered, untreated. He was transferred to a negative-pressure room at Airway Heights Corrections Center in Spokane, where he would spend three and a half months. There, he was shocked to see Oya through his small isolation-cell window. Though they couldn’t hear each other through the glass, “we do a sign language,” Lagerquist said. “We read each other.” Oya signaled that he, too, was in isolation for TB. “That’s when I realized I got it from him,” Lagerquist said. “I’m putting things together—that’s what that pain was in my chest the whole time…. I didn’t know that the person that I was exposed to was my homeboy.”

The isolation was traumatic. “I’m treated like I’m being punished,” Oya said. His already limited tethers to the outside world—highly restricted and recorded phone calls and e-mails—were almost entirely severed. “I didn’t do anything to be treated like this. I didn’t get in trouble. Why am I locked in this room, not using the phone more than one time a day?”

Another Stafford Creek cellie of Oya’s, Jesus Ancheta, whom Oya refers to as his cousin, also described feeling punished for his diagnosis. “I got five minutes [of phone time] if the COs [corrections officers] were willing to take me out—if they were in a good mood,” Ancheta said. Sometimes, he’d go a week without being allowed to call his 15-year-old son. Ancheta had long hair, so he usually bought shampoo at the prison commissary. (The prison’s standard-issue shampoo came in tiny bottles and was of poor quality.) But the isolation cut him off from the commissary, too.

For weeks, Ancheta was denied access to books, TV, and radio. Left alone with his thoughts, “I was going down my own rabbit holes,” he said. Ancheta, who is a member of the Cowichan Tribes, thought a lot about how TB, often brought to North America by European colonists, devastated many tribes throughout the 20th century and continues to disproportionately affect Native populations. He struggled to keep his composure in conversations with his family, not wanting to reveal his anxiety.

After several weeks, the state Department of Corrections moved another man they suspected of having TB into Ancheta’s isolation room with him. Ancheta and his new cellie were told to wear masks 24 hours a day. Ancheta was terrified. “Why would you guys even put us in this position of being able to transmit it back and forth to each other? I don’t know anything about it. You guys are the doctors.”

Trapped in a system that gave him little confidence, Ancheta told me, “There’s nothing I can do to save myself other than lay here and have faith in what they got in store.”

Thanks to their lengthy antibiotic treatments, Oya, Lagerquist, and Ancheta are no longer infectious. But TB has left them with debilitating symptoms. Lagerquist had always considered himself healthy. “I’m not young,” he told me, “and I’m not old either.” Now, when he plays basketball or lifts weights, he gets winded quickly. “When I cough, I have a different, deep cough, like I smoke or something. I get dizzy and light-headed. I start seeing little spots and stars.” He is worried about his upcoming release. “When I get out of prison, I’ll have to get a job. I’ve never had a job before. I’ll probably have to do something that consists of hard labor. How does that play out with having ongoing health problems?”

But Lagerquist was even more concerned about Oya: “When he’s not coughing, you want to go check on him to see if he’s all right.”

In September 2022, the state Department of Labor and Industries fined Stafford Creek Corrections Center more than $80,000 for “putting workers at risk during [a] tuberculosis outbreak.” The money would go toward a workers’ pension fund. Three workers had died of Covid at Stafford Creek, and the prison had been cited once before for failing to require workers to wear masks and socially distance during Covid-19. But the citations failed to mention that five people incarcerated there had also been killed by Covid—giving Stafford Creek the highest reported death toll of any prison in the state.

So far, there has been no compensation at all for the incarcerated people or their loved ones whose lives have been permanently altered by the largest TB outbreak in 20 years. And there is no indication that anything has been done to prevent another outbreak.

The men I spoke with heard through the prison grapevine of dozens of others being infected with TB at Stafford Creek and Clallam Bay. But they were never officially told how many people were infected or where. And while the Department of Corrections has a Covid-19 Data Dashboard, there is no easily accessible information on TB cases or infections in the prison system.

The DOC and the Department of Health told me that the outbreak included 22 people who had been diagnosed in prison and three others diagnosed after their release. Confusingly, though, the state’s official TB numbers don’t include cases among incarcerated people. (A DOH representative told me that future reports will include cases that “are not assigned a county/jurisdiction.”)

The lack of data on the outbreak also raises the already high bar for seeking recourse described by the incarcerated activist Jessica Phoenix Silvia. The Prison Litigation Reform Act requires that incarcerated people file a grievance (a formal complaint to the prison officials whose power they are under) before filing a lawsuit. (The PLRA, signed by President Bill Clinton in 1996, was intended to reduce the volume of lawsuits against the country’s rapidly expanding prison system—in particular those complaining of cruel and unusual punishment.) In Washington State, grievances have to be filed within 20 days of an incident and go through four levels of appeal.

The obstacles to filing complaints are made harder still by what is known as “diesel therapy,” or the practice of shuttling people that the DOC deems challenging from prison to prison. Oya had meticulously documented his search for medical care, but after each of his transfers, he had to wait weeks for his belongings and careful notes to catch up with him, making it nearly impossible to complete his grievances. In late November 2022, he was told that he would be transferred again. Oya hoped that he’d be relocated closer to his family, but he couldn’t help feeling that his constant movement was a form of retaliation.

“You have 60 seconds remaining,” a cold recorded voice said, cutting into one of my phone calls with Oya. He spoke quickly, trying to get more words in. “I feel like I started this,” he said. “I truly have a heavy heart. My family and people that I’m really close with in prison, they always tell me, ‘Hey bro, it’s not your fault. It’s these guys’ fault. They neglected to take care of you.‘“