As a student in Paris in the fall of 1990, my lodgings were the envy of my peers—even if the means by which I came about them were not. While fellow language students from my university in Edinburgh were stuck in soulless suburbs, I was ensconced in Rue des Fossés Saint-Jacques, a short walk from the Jardin du Luxembourg and around the corner from the Panthéon.

I had been lucky to find anywhere at all. Flat hunting in Paris is tough for anyone; being Black made it considerably tougher. People would ask about your “origins” when you called. If they didn’t, you’d turn up and find that the apartment was mysteriously no longer available.

All the other students were white and had found housing; I was still in a youth hostel. I stuck a note in the English Church stating, “Black British student, seeking accommodation.” A British blue blood saw it and said “God spoke” to him, and he started inquiring on my behalf. I was just about to return to Scotland to ask whether there was a less racist part of the Francophone world they could send me to, when a call came through to the hostel from a man I didn’t know saying a place had been found.

The flat was lovely. My landlady, an Eastern European specialist with French radio to whom I taught English, was delightful and one of the main reasons I ended up choosing journalism as a profession. But Paris still provided one of the most intensely racist experiences I had ever encountered. The color bars in nightclubs—many simply wouldn’t allow Blacks to enter—were bad enough, but one night I was beaten up by the French police in the Métro. They assumed I had drugs; I didn’t.

The most exhausting aspect was the constant stop-and-frisk by the police, which happened several times a week, usually not far from the mostly white area where I was staying. The sight of a young Black man in sweatpants and braids was sufficiently suspicious that I learned to always carry my passport with me. Whether I was out early in the morning getting the paper and a coffee or wandering back late at night from a film, police would often stop me and radio in my details—the fact of me—to make sure I had a right to be there.

On November 30, literally in the shadow of where this harassment took place, the American-born Black singer, dancer, and resistance agent Josephine Baker will be reinterred in the Panthéon—next to the nation’s great and glorious, including the philosophers Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the novelists Victor Hugo and Émile Zola. Baker will be only the sixth woman, the third Black person, and the first Black woman to be laid to rest there.

The petition to move Baker’s grave from Monaco, where she died in 1975, was initiated by the writer Laurent Kupferman, who told The New York Times he thinks President Emmanuel Macron approved the reinterment “because, probably, Josephine Baker embodies the Republic of possibilities. (Baker’s actual remains will not be disinterred. Instead the French are taking soil from the various places where she lived and burying that in the Pantheon.) How could a woman who came from a discriminated and very poor background achieve her destiny and become a world star? That was possible in France at a time when it was not in the United States.” It seems not to have occurred to anyone to ask whether it would be possible now for a Black woman to rise to such heights if she had been born in France under similar circumstances.

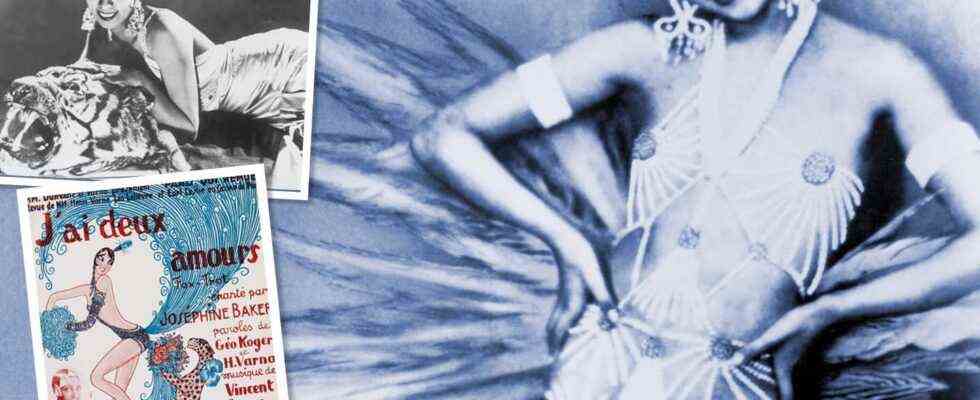

Nonetheless, the question of how and why Baker came to be so fêted by the French state is a good one. Born into poverty in segregated St. Louis in 1906, she left an unremarkable singing and dancing career in the US and arrived in France in 1925 as part of La Revue Nègre, quickly making a name for herself, first on the stage and then in film. Outrageous, playful, and sensual, she performed the “Danse Sauvage” in just a feathered skirt and then another, more provocative number in a skirt made of 16 bananas. She scandalized and titillated Paris, appealing to the sense of the primitive and the exotic that pervaded Europe during the Jazz Age. “She is in constant motion, her body writhing like a snake or more precisely like a dipping saxophone,” wrote the critic Pierre de Régnier. “Music seems to pour from her body. She grimaces, crosses her eyes, wiggles disjointedly, does the splits and finally crawls off the stage, stiff-legged, her rump higher than her head, like a young giraffe.”

With her pet cheetah, Chiquita, her pet pig, Albert, and her “Rainbow Tribe” of 12 children of different races adopted from all over the world, her eccentricities were indulged when not celebrated.

Baker loved France, and France loved her. Her hit song “J’ai Deux Amours/Mon Pay et Paris”—“I Have Two Loves/My Country and Paris”—misleadingly suggested that she was conflicted about her allegiances. Soon after marrying a Frenchman in the late 1930s, she renounced her US citizenship and became French.

Baker was something of a pioneer in this journey, but she was by no means alone. During the decades immediately before and after World War II, a significant cohort of Black artists, facing repression in the US, would seek exile in France—where they found not only acceptance but adulation. “There is more freedom in one square block of Paris than there is in the entire United States of America!” wrote the novelist Richard Wright, who moved to France in 1946, claimed French citizenship, and died there in 1960.

You could form a big band with the musicians who found a home in Paris, including Don Byas, Kenny Clarke, Dexter Gordon, and Bud Powell. You could fill a library with the works of Black writers who did the same, like Wright, James Baldwin, Chester Himes, and William Gardner Smith.

“Paris,” wrote Tyler Stovall in Paris Noir, “beckoned with a vibrant intellectual community sharply critical of American racism and the American perspective on the cold war in general. Given [the alternative], the decision for exile, while certainly not easy, had a forceful and undeniable logic.”

But for Baker, this love affair with Paris was far more enduring, intense, and consequential than for other artists. She enjoyed more freedom, acclaim, and status in France than she could ever have hoped for in the United States. “I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. And much more,” she told the March on Washington from the podium. “But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad.”

During World War II, Baker leveraged her renown and celebrity to extract information from diplomats and dignitaries, which she passed on to Gen. Charles de Gaulle’s Free French forces. She used her home in the Dordogne region to shelter resistance fighters. And thanks to her fame, she was able to travel much of the continent as a courier for the resistance. In August 1961, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and made a chevalier of the Legion of Honor, the highest French decorations, both military and civil, for her services to the French resistance.

Baker’s honors, whether medals for the living or entombment of the dead, are of course ceremonial. When Alexandre Dumas, the author of The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers, was interred in the Panthéon in 2002, his ashes were carried there by four musketeers, dressed in costumes designed by a man from the same southwestern region as the Musketeers protagonist D’Artagnan.

The decision to inter someone in the Panthéon is essentially political. It’s the president’s choice. As such, it forms a small part of his legacy—offering an opportunity for soft intervention, at no material cost, into the issues of the moment. Dumas, whose grandmother was a Haitian slave, had been dead for more than 130 years before he was moved. He was the second person of African ancestry to be buried there. (Félix Éboué, the French Guyanese–born administrator of Guadeloupe, was the first, in 1949.) The timing was no coincidence. Jacques Chirac’s first presidential term had seen a multiracial French soccer team win the World Cup for the first time. In Paris, the French Parliament acknowledged both the slave trade and slavery as a crime against humanity at a time when the extreme-right National Front’s Jean-Marie Le Pen shocked the world by coming in second in the presidential election.

“The French Republic today cannot satisfy itself with simply honoring the genius of Alexandre Dumas,” Chirac said as Dumas was laid to rest in the Panthéon. “It must correct an injustice: an injustice that blighted Dumas since childhood, just like the injustice branded into the flesh of his slave ancestors.”

Over the years, there have also been attempts to correct the huge gender imbalance in the Panthéon, whose entrance is embossed with the message “To its great men, a grateful fatherland.” But it was centuries before Marie Curie became the first woman to be interred there under her own merit, in 1995. Between 2015 and 2018, there were three more: resistance fighters Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz and Germaine Tillion and feminist Simone Veil. France remains one of a handful of European states that has never had a female leader.

To fully understand the politics behind Baker’s impending commemoration, we must first realize that the long-standing love affair between African American artists and Paris was not all one way. France got a lot out of it too. The republican ideal on which the nation was founded rejects multiculturalism in favor of universalism, claiming, “We’re all French—and all other differences are not only secondary but irrelevant and even divisive.” In a nation that understood citizenship as indivisible, race was deemed invisible.

But if race did not officially exist, racism was nonetheless present. The French empire and its various overseas territories—which spanned Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific—depended on strict racial hierarchies. The fight to reimpose slavery in Haiti and the struggles against independence—particularly in Algeria and, to a lesser extent, Vietnam—were brutal.

Geopolitics also played a role in France’s welcoming of African Americans—particularly in the immediate postwar era, when American hegemony was most fiercely resented. The French delivered more votes to the Communist Party in 1946 than to any other; many mocked what they regarded as the cultural imperialism of the Marshall Plan as “Coca-colonization.” Embracing exiles from their ally-cum-rival gave the French a sense of being morally and culturally superior—even as they wrestled with their military and economic inferiority.

In the white French gaze, Black American artists in particular were from—but not entirely of—the United States: central to a version of its culture but absolved from the consequences of its power. They inhabited a liminal racial and political space in which their racial difference was embraced because the French found themselves neither familiar with nor implicated in the conditions that made their exile necessary. Theirs was an honorary, if contingent, racial status. They were free, for example, to write about racial atrocities in America—but not to comment on colonial atrocities committed by France, either at home or abroad.

Some found this space if not adequate then at least sufficient, given what they had left behind. Others did not. The freedom Wright found in that one square block of Paris was appreciated. The challenge came if you tried to step outside it. In the third volume of her autobiography, Singin’ and Swingin’ and Gettin’ Merry Like Christmas, Maya Angelou reflected on the frosty reception meted out to a Senegalese friend when he accompanied her to a party in 1954. “Paris was not the place for me or my son. The French could entertain the idea of me because they were not immersed in guilt about a mutual history—just as white Americans found it easier to accept Africans, Cubans or South American Blacks than the Blacks who had lived with them foot to neck for two hundred years. I saw no benefit in exchanging one kind of prejudice for another.”

In James Baldwin’s essay “Alas, Poor Richard”—one of many oedipal swipes he leveled at Wright, his former mentor and friend—he wrote, “Richard was able, at last, to live in Paris exactly as he would have lived, had he been a white man, here, in America. This may seem desirable, but I wonder if it is…. It did not seem worthwhile to me to have fled the native fantasy only to embrace a foreign one.”

In October 1961, two months after Baker received her Legion of Honor, the Paris police, led by Maurice Papon, massacred hundreds of Algerian protesters and arrested more than 10,000 following an independence march. (Decades later, Papon would be convicted for his involvement in the deportation of more than 1,600 Jews from Bordeaux during the Second World War.)

This year, even as plans were being made for Baker’s reinterment, efforts to entomb the Tunisian French lawyer, feminist, essayist, and former MP Gisèle Halimi in the Panthéon were thwarted. Halimi, who died in 2020, campaigned on a range of left issues, including abortion, wealth redistribution, and human rights.

She was also a counsel for the Algerian National Liberation Front and a devout anti-colonialist. The campaign to have her buried in the Panthéon has so far been rebuffed because the president’s team believes her inclusion would be too divisive.

“African-Americans have been celebrated in France both as a way to oppose the American societal model by showing French color-blindness as inclusive and as an effort not to address the colonial history of France and its legacies,” said Sarah Mazouz, a sociologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research and the coauthor of For Intersectionality.

Which brings us back to my student experiences of police harassment.

It is not possible to square the lived experience of Black and Arab people in France, particularly the young, with the French insistence on color-blind universality. Indeed, following a spate of terror attacks, the riots of 2005, and the rise of the far right—currently enjoying a surge in the polls—such reconciliation is even more difficult 30 years on.

Polling on racist attitudes is notoriously rare in France—it is illegal to collect data based on race, ethnicity, and religion. But in a poll released in June last year of Seine-Saint-Denis, a neighborhood that has a significant number of Black and Arab inhabitants, more than 80 percent said they believed that race or ethnicity was the basis of discrimination in dealing with the police or in employment.

A survey by the Migration Policy Institute in 2012 found that more than a third of children of immigrants believe they are not considered French by other citizens, while 45 percent cite their origins as being somewhere other than France, suggesting a significant degree of alienation. A 2014 survey revealed that more than a third of the French acknowledge being racist. A poll from last year revealed that one in four French believe their country’s empire was something to be proud of, while one in seven consider it to be a source of shame. (The British were both more likely to be proud and more likely to be ashamed, while the Dutch seem to be almost entirely without remorse.)

Last year’s Black Lives Matter protests, which pollinated across Europe, finding a home in the continent’s local struggles, brought these contradictions to the fore. Some of the biggest demonstrations were in Paris. Many European leaders at the time dismissed the notion that the protests had any domestic relevance. But the French were more insistent than most, claiming that “white privilege” and “intersectionality” were American concepts imported to sow division and rancor.

Macron even took time out of a national address on the coronavirus to pledge his “uncompromising” opposition to racism, but warned that this “noble fight” was rendered “unacceptable” when “usurped by separatists” who want to divide French society.

The backlash has been the most intense within the academy (see “Europe’s War on Woke,” page 20), with one veteran social scientist, Gérard Noiriel, claiming race had become a “bulldozer” laying waste to other disciplines. In January, the Observatory of Decolonialism and Identitarian Ideologies was founded by outraged academics, who declared, “Today we are confronted with a wave of identity politics at the heart of higher education and research.” There is little doubt whom they blame for this wave. “There’s a battle to wage against an intellectual matrix from American universities,” said Jean-Michel Blanquer, the French education minister.

Attacks on critical race theory are hardly unique to France; they remain the default position of the right both in Britain and the United States. What’s different in France is that some of these broadsides are coming from liberals and the left, on the basis of color-blind republicanism.

The tensions this creates were laid bare recently in a spat over the repertoire of the Paris Opera. Like many public institutions on the continent, the Paris Opera responded to the Black Lives Matter demonstrations by conducting a diversity review. Following the review, the artistic director, Alexander Neef, announced that the company would no longer be performing some works—and there would be no more actors in blackface or yellowface.

Such has been the standard response of cultural bodies in the West over the past year and a half as they shed some of the less enlightened elements from their inventory. That Marine Le Pen, the leader of the extreme-right National Rally Party, took to Twitter to condemn “anti-racism gone mad” was not surprising. But she was joined by the editor of the liberal Le Monde, Michel Guerrin, who claimed that the Paris Opera was practicing “self-censorship” as it pandered to identity politics. True, the director was German, but he had previously worked in Toronto and, Guerrin pointed out, had “been wallowing in American culture for 10 years” (a slight rooted in identity politics if ever there was one).

Such is the context in which Baker’s remains travel to the Panthéon. The African American artists’ pilgrimage to Paris, of which she was the patron saint, is now mostly the stuff of nostalgia (though Ta-Nehisi Coates did camp out there for some time after Between the World and Me came out), captured in walking tours, plaques, and retrospectives. The world moved on. For all its faults, America, with its Black former president, Black current vice president, and sizable Black middle class, is not what it was when Baker crossed the Atlantic, even if in some respects the country appears to be going backward. Today, France’s toxic blend of far-right extremists, secular fundamentalism, and racial denial has left it even further from the nonracial democracy it imagines itself to be.

Yet the competition over which country is least racist no longer holds quite the same appeal. The space that African Americans once occupied here, limited as it was, is no longer available. All that is left is the memory of it. And it is this, along with Josephine Baker, that the French are set to dig up—only to bury again.