There were streakers, kissers and wannabe prize fighters. There were arrests, threats and flying chairs. There were bruises, there was blood and there was beer. So, so much beer.

There was plenty of blame to pass around: the fans, the umpires, the team officials, the managers, local broadcasters and radio hosts. Oh, and according to one Cleveland resident, the real instigator causing that evening’s mayhem? The moon. And that’s not a reference to the fans who yanked down their pants and showed Rangers players their backsides.

Fifty years ago, chaos descended upon Municipal Stadium on 10-Cent Beer Night. Now, the infamous events of June 4, 1974, when an alcohol-fueled crowd spilled onto the field, confronted players and forced a forfeit, are often viewed in a light-hearted manner, the stuff of commemorative T-shirts and parodied ballpark promotions.

But at the time? Cleveland’s sports chroniclers considered it a black eye for Cleveland on a night that resulted in many of them.

Texas manager Billy Martin: “The fans showed the worst sportsmanship in the history of baseball.”

Cleveland manager Ken Aspromonte: “I’ve never seen anything like that in all my life and I have played baseball all over the world.”

Umpire Nestor Chylak: “They were uncontrolled beasts. I’ve never seen anything like it except in a zoo.”

Let’s travel back in time and dig into the archives of The Plain Dealer to re-live one of the most surreal scenes ever to unfold on a baseball field.

‘They would have killed him. I guess these fans just can’t handle good beer’

The attendance that night: 25,134. Beers sold that night: 65,000. A Guardians spokesman estimated an average crowd today consumes about 23,500 beers.

Columnist Hal Lebovitz surmised that half of the fans “drank little or no beer,” which meant those participating accounted for about five Stroh’s each. “I saw five fans stand in the beer line, each getting the maximum six cups,” Lebovitz wrote. “That’s 30 beers. Some of them drank two cups and the others inhaled nearly 10 apiece.” For a buck, he added, a fan could snag a 50-cent bleacher seat and five beers. A security guard was quoted saying he saw “kids that couldn’t be more than 14 years old drinking beer.”

“Small wonder the bleachers were quickly sold out,” Lebovitz wrote. “Not even free soup or bread would have caused those long lines.”

The team increased its security presence from the customary 32 guards to 48. Early in the game, it was merely a comedic spectacle, though one rated “R.” Dan Coughlin wrote: “A woman walked up to the home-plate umpire Nestor Chylak and tried to kiss him. Compared to what followed, this was cute.”

Fans breached the field of play in the middle innings. They showered Martin with beer when he disputed a call, and he blew kisses back at them. As beat writer Russ Schneider detailed: “In the sixth inning, one of the youths who raced across the outfield stopped and disrobed — then streaked back and forth until he escaped over the right-field fence and into the arms of a policeman.”

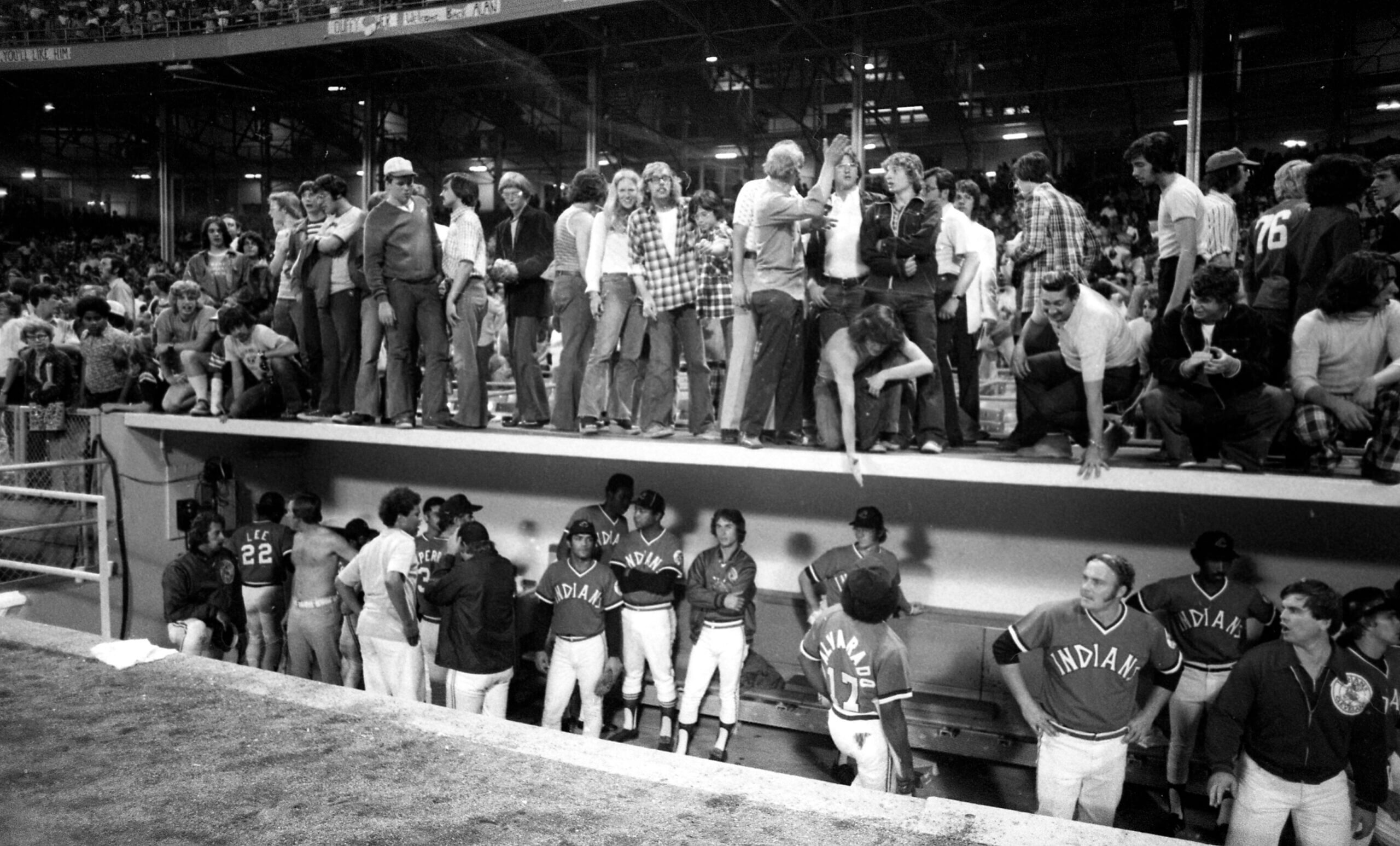

“The brew-propelled bleacher fans began to hop into the better seats, roam around the park, disturb the bullpens, jump over the fence and onto the field,” Lebovitz wrote. “The hooliganism was not confined to bleacherites only, but they were in the vast majority.” Umpires, ushers, security guards and the grounds crew spent much of their time herding fans off the field and scooping up their discarded clothing, empty beer cups and other trash.

In the seventh, fans tossed a string of firecrackers near the Rangers’ bullpen, forcing the relievers to scamper across the field to the visitors’ dugout. Cleveland’s relievers followed suit a half-inning later. That led to Martin sticking with reliever Steve Foucault through the end of the game since the bullpen, as Schneider noted, “was barren of players.”

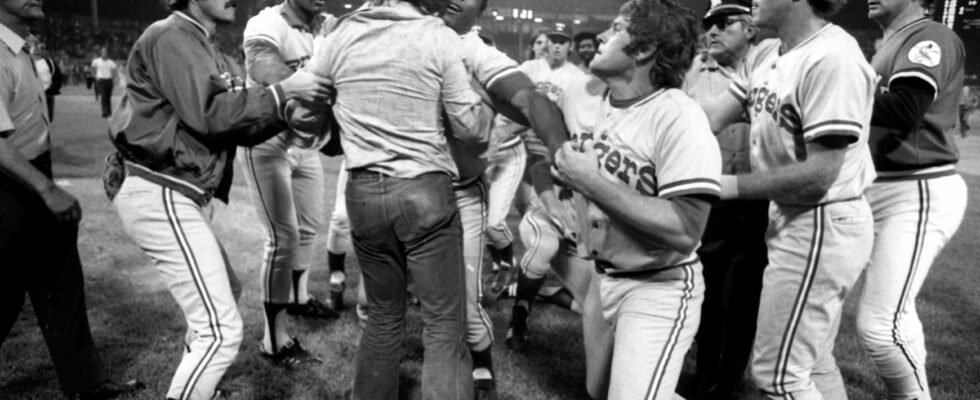

Cleveland erased a 5-3 deficit in the ninth and appeared poised for a walk-off win when all hell broke loose. It was a ballpark riot, lasting nearly 10 minutes, players versus fans in one of the ugliest scenes ever to grace a baseball field. From Schneider’s dispatch: “A couple of spectators leaped onto the playing field and tried to steal the cap from the head of Jeff Burroughs, the Rangers’ right fielder. Burroughs fought back and, quickly, scores of youths jumped over the railing and onto the field — while players from both the Indians and Rangers raced to the defense of the outfielder. This time the Indians and Rangers — who fought each other last Wednesday night in Arlington, Texas — joined forces to protect themselves from the unruly mob.”

Cleveland pitcher Tom Hilgendorf absorbed a metal folding chair to the head. Chylak was cut on the hand. Police had caps and badges stolen. The bases were swiped — and not by some speedy infielder. There were a dozen arrests.

“Maybe it was silly for us to go out there,” Martin said after the game, “but we weren’t about to leave a man out there on the field unprotected. It seemed that he might be destroyed. They would have killed him. I guess these fans just can’t handle good beer. There were some knives out there, too. We’re fortunate somebody didn’t get stabbed.”

Coughlin’s story asserts that someone “standing in a mob on top of the Texas Rangers dugout punched a newspaper reporter in the side of the head several minutes after the riot at the Stadium apparently had subsided. ‘I’ll kill you,’ said the youth, who seconds later blindsided the reporter again. ‘And if Burroughs comes out on that field tomorrow night, I’ll kill him.’”

Jeff Burroughs, center, is escorted off the field after fighting with fans. (Paul Tepley Collection / Diamond Images / Getty Images)

“I could see that there was sort of a riot psychology,” Burroughs said. “You have to realize all I had to protect myself with was my fists.”

The game was ruled a forfeit in favor of the Rangers, the first forfeit since September 1971, when the Senators played their final game in Washington D.C. before relocating to become … the Rangers. Cleveland pitcher Dick Bosman, a member of that 1971 Senators team, said the fans in Washington “were only looking for mementos” when they disrupted the game. After 10-Cent Beer Night, Bosman said: “This was a mean, ugly, frightening crowd.”

Cleveland’s players, bloody, bruised and shouting in frustration, returned to the home clubhouse. Aspromonte collected himself for 10 minutes before telling reporters in a soft voice: “Those people were like animals. But it’s not just baseball, it’s the society we live in. Nobody seems to care about anything.’ We complained about their people in Arlington last week when they threw beer on us and taunted us to fight, but look at our people. They were worse. I don’t know if it was just the beer.”

GO DEEPER

Beers in the hot tub, holes in the wall: Tales from Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium clubhouse

Martin called Aspromonte to thank the Indians for coming to his team’s defense. The Rangers remained in their locker room for nearly two hours before returning to their hotel with a significant police presence. Umpires exited in a private car that pulled up outside their locker room.

Frank Ferrone, chief of stadium security, shook his head and acknowledged it was the worst incident in the history of Cleveland baseball as he spoke with reporters.

“We would have needed 25,000 cops to handle this crowd,” he said.

‘I don’t know who to blame, but I’m scared’

Lebovitz wrote: “They weren’t baseball fans. They wanted the beer. Thus, in essence, the Indians’ management wasn’t promoting baseball. It was pushing beer.”

The cheap-beer marketing ploy wasn’t unique to Cleveland. The Brewers and Rangers had used similar promotions. The Indians had a nickel-beer night a few years earlier. The previous summer, Clevelanders could swig 10-cent beers at a variety of downtown events, including a rib burnoff, an art show and the All Nations Festival, where the libations were so popular that “more than 1,000 gallons were pumped in just a couple of hours,” according to a Plain Dealer article.

In fact, the Rangers held the same promotion a week earlier, the night they tangled with the Indians in an eighth-inning brawl. Lenny Randle dropped down a bunt and ran several feet inside the baseline to collide with Cleveland reliever Milt Wilcox. Randle had leveled infielder Jack Brohamer to break up a double play, so Wilcox greeted him with a pitch uncomfortably inside. Cleveland’s John Ellis tackled Randle, and the dugouts and bullpens emptied. As the Indians left the field, fans pelted them with beer.

Schneider wrote: “(Dave) Duncan, still wearing his catcher’s equipment, shouted at one of the fans, who, in turn, challenged the Cleveland player to fight. As Duncan stood there arguing — and with the total absence of any policemen or security agents — another man threw a cup of beer in Duncan’s face. It incensed Duncan and he attempted to climb over the roof of the dugout to reach the fan while his teammates, coaches and Aspromonte clung to his body to keep him away from the spectators. At the same time, several fans crawled on the roof of the dugout and continued their taunts and insults. After nearly five minutes, three policemen rushed to the dugout with hands on their pistols.”

For a week, the hype built. Pete Franklin fanned the flames nightly on his popular Cleveland radio show. Lebovitz chided broadcaster Joe Tait for urging fans to “Come out to Beer Night and let’s stick it in Billy Martin’s ear.” Tait called Lebovitz to say he only made that declaration once, and only did so because Martin insisted there would be no hostile environment in Cleveland because the team didn’t have enough fans.

“The impression may not have been the one Joe intended,” Lebovitz wrote. “But that’s the inference the listeners got. Joe, with his high-voltage delivery, conceivably helped create an atmosphere that led to the final scene.”

Tait, though, pointed out a visual in the sports section the morning of the game that had a team mascot wearing boxing gloves. Lebovitz admitted that was a mistake. “In retrospect,” he wrote, “I felt ill over our contribution to the night’s events.” Lebovitz opted not to pen a column pleading with the team to postpone Beer Night because of the previous scrap between the teams. He didn’t think his words would have carried much weight.

“These people probably came out with sort of a chip on their shoulders,” said Rangers catcher Duke Sims, “and then got beered up.”

There were other culprits, too. Chylak said he “saw trouble coming as early as the seventh inning” and Lebovitz wrote the umpires began plotting their own exit, but “didn’t think beyond personal safety.”

Cleveland’s executive vice president, Ted Bonda, told Schneider he considered handing Gaylord Perry a microphone to deliver a calming message to the fans in the seventh inning, “but I talked to somebody who talked me out of it. I wish now I had obeyed my gut feeling, but hindsight is better than foresight.”

Schneider wrote that a stern warning would have sufficed. He also stressed umpires should have ordered the team to plead with the fans. When Mets fans tossed debris at Pete Rose in the playoffs the previous year, the umpires ordered the PA announcer to threaten fans with a potential forfeit. Manager Yogi Berra and veterans Willie Mays and Tom Seaver stepped onto the field and asked fans to “give us a chance to win on the field.” Schneider wrote, “This, it would seem, should be a common practice as well as common sense.”

Lebovitz also pinned some blame on team officials for not preventing fans from shifting to closer seats that aided their fence-hopping and for not calling city police when it became apparent the fans couldn’t be contained.

“But the major blame,” he wrote, “must fall on Beer Night. Without the 10-cent beer, the game would have been played to its proper conclusion in a relatively normal atmosphere. The beer brought out twice as many fans as expected and it brought out the worst in many of them, particularly the teenage kids who can’t handle it.”

Aspromonte: “I don’t know who’s to blame, but I’m scared.’”

Martin feared retaliation when the Indians returned to Texas in late August. He vowed to use his radio show to highlight how Cleveland’s players actually came to their aid.

“It was an unfortunate thing last week when that fan threw beer in Aspromonte’s face,” Martin said, “but it shouldn’t have caused this. I really was scared. I was afraid someone was going to get seriously hurt. Someone could have had an eye put out.

“That’s probably the closest we’ll come to seeing someone getting killed in the game of baseball. In the 25 years I’ve played, I’ve never seen any crowd act like that. It was ridiculous.”

A woman called The Plain Dealer newsroom to inform them they had omitted the driving force behind the night’s events: “There was a full moon.”

Some fans in Cleveland climbed atop the team dugouts and a few later charged the field. (Paul Tepley Collection / Diamond Images/Getty Images)

“Beer Night became the gasoline that caused it to burst into full flame,” Lebovitz wrote. “There is no better fuel than alcohol.

“The whole evening was a shame. It would be a tragic mistake to slough it off — to blame it on the full moon. In that case, the riot will have taught us nothing.”

‘Beer, a hot dog, popcorn and a lot of bellyaching’

Cleveland public address announcer Bob Keefer warned fans ahead of the game the following night that they would be prosecuted if they entered the field of play. The message was met with applause.

The Indians had two more 10-cent beer nights scheduled. In the early innings, when the only madness was a few young fans who had run across the field, Bonda had no qualms about the future promotions, as he told The Plain Dealer: “We plan to have them. These are young people. They are our fans. Where have they been? I’m not going to chase them away. They haven’t interrupted the game.”

He spoke too soon.

Heaton criticized Bonda and general manager Phil Seghi for downplaying the events and leaving the game early.

“The better course would be to admit some misjudgment,” Heaton wrote, “in anticipating the size of the turnout, providing adequate security forces and in decisions on how to handle the various incidents that happened. They certainly didn’t feel that matters would get so hairy as they did in that last inning or both would not have left the game early and missed a first-hand view of the melee.”

The day after the brouhaha in Cleveland — one of only five forfeits in the last 70 years — Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson said: “Beer doesn’t help. But I would be the last man to suggest that you ban beer at a ballpark. That’s the name of the game — beer, a hot dog, popcorn and a lot of bellyaching. I’ll tell you, if we ever had 10-cent beer at Shea (Stadium), it would be a disaster.”

A half-century later, that night’s memories, softened over time, prevail through popular T-shirts around Cleveland — at one point, available at the Progressive Field team store — and copycat promotions. The Portland Pickles, a collegiate summer team, are partnering with a brewery for a 10-cent Beer Night on Tuesday. As their promotion reads: “10 Cent Beer Night went down as one of the worst failed promotions in sports history. That’s why we’re bringing it back.”

American League president Lee MacPhail initially declared “beer nights will not be permitted at Indians home games in the foreseeable future.” He later backtracked, and the Indians held another beer night on July 18, 1974, but with stricter purchasing limits.

Bonda feared the fracas would hurt the club’s attendance. Heaton wrote he didn’t think there would be a correlation, but he did predict team officials would use it as a convenient excuse if the Indians didn’t draw better. Ultimately, they attracted more than 1.11 million to Municipal Stadium, the club’s largest attendance figure for a quarter-century stretch (1960-85).

“The fans know that riots are rare occurrences,” Heaton wrote, “and that Tuesday’s outburst very well may never be part of the Cleveland scene again.”

(Top photo: Paul Tepley Collection / Diamond Images / Getty Images)