An assassin works from a partial understanding of the world. If not literally a hashishi, as suggested by the word’s etymology, an assassin must nevertheless see the world in tunnel vision, his victim viewed through the lens of a scope. The vast, complex network of humanity to which he and his victim belong, with contending narratives and blurred individual motives, cannot be allowed to exist. To do so would be to fail as an assassin.

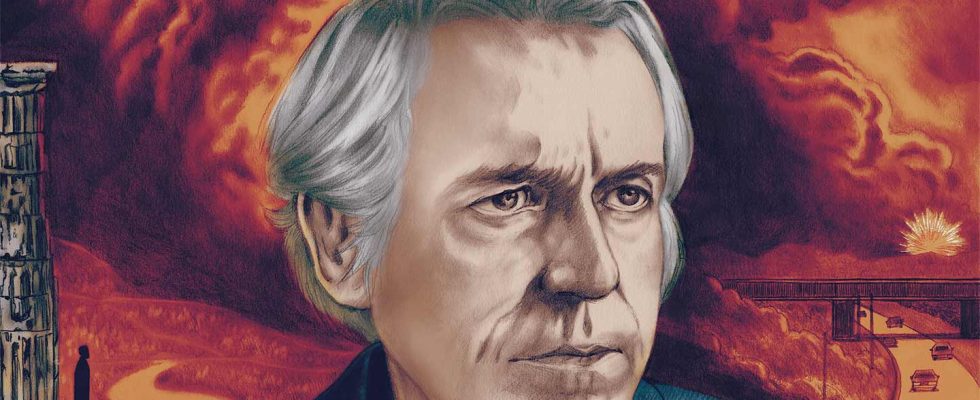

A Don DeLillo novel grasps both the assassin’s monomania and the contradictory, counterintuitive world of which it is a part. It is capable of displaying fidelity to both perspectives, brushing one against the other to edge its way toward a fictional truth that neither can uncover on its own. Six novels published in the 1970s established this principle, but the approach truly came into its own only with Libra (1988), DeLillo’s ninth novel. “Hashish. Interesting, interesting word,” a character says to Lee Harvey Oswald as the novel uncoils toward its climactic moment in Dallas with the Kennedy assassination. “Arabic. It’s the source of the word assassin.”

This knowingness, highlighted by the verbal certainty of the character, only throws into sharp relief all that is unknown, confusing, and contradictory in the novel. By its end, we are still uncertain whether either the shadow men who set the Kennedy assassination in motion (including the character riffing on the etymology of “assassin”) or the fastidious figures who attempt to piece the event together have any greater grasp of the whole than Oswald has. Nothing is knowable in full in the world as depicted by DeLillo, and this is why the Kennedy assassination is the prime exhibit in this hall of mirrors. “We are not agreed,” DeLillo wrote in an essay for Rolling Stone a few years before Libra’s publication, “on the number of gunmen, the number of shots, the origin of the shots, the time span between shots, the paths the bullets took, the number of wounds on the president’s body, the size and shape of the wounds, the amount of damage to the brain, the presence of metallic fragments in the chest, the number of caskets, the number of ambulances, the number of occipital bones….”

Libra is the last of three DeLillo novels from the 1980s that have now been reissued by the Library of America. With appendices, notes, new prefaces by the author as well as his Kennedy assassination essay and another on neo-Nazis in the United States, the volume runs to over 1,000 pages. Including The Names (1982), a novel about a cult set mostly in Greece, and White Noise (1985), a Midwestern campus drama that devolves into existential uncertainties, this is a compilation that grasps everything while also pointing out that an excess of material may, in terms of understanding, easily amount to nothing. We learn about fossil fuels and risk analysis, Hitler studies and toxic chemicals, millenarian cults and shadowy operatives of the deep state, but at these novels’ core are the mysteries of American power at home and abroad. Written in the fog of the Cold War, they take the story of America’s postwar years, usually seen as a triumphal rise to perpetual dominance and the end of history, and convert it into the story of a long, chaotic decline. Perhaps for this reason, these American novels written over the course of a decade feel like they are recording half a century, and if they speak powerfully of the past, they simultaneously manage to address the present.

The Names, probably the least known of this trifecta, is soaked in the triumphant self-mythologizing endemic to a superpower. Its protagonist, James Axton, is an American working as a corporate risk analyst in Athens. Axton’s days are an expatriate’s seesawing from mundane activity to joyless pleasure, his sensibilities always at odds with a jagged, old city that now serves as a forward operating base for Americans working the levers of finance, oil, and military aid in Asia and the Middle East.

An estranged family—Axton’s Canadian wife, Kathryn, lives on Kouros, an island in the Cyclades, along with their precocious child Tap (some of whose writing appears in the novel and was apparently taken by DeLillo from the childhood scribbles of Atticus Lish, son of his friend Gordon)—adds a biographical touch to Axton without providing him with the slightest dose of interiority. Neither his incessant first-person narration nor the endless conversations he holds with the other expats provides anything like a self. To Kathryn, he explains his forthcoming trips to “Istanbul, Ankara, Beirut, Karachi” in the following manner:

In effect I review the political and economic situation of the country in question. We have a complex grading system. Prison statistics weighed against the number of foreign workers. How many young males unemployed. Have the generals’ salaries been doubled recently. What happens to dissidents. This year’s cotton crop or winter wheat yield. Payments made to the clergy. We have people we call control points. The control is always a national of the country in question. Together we analyze the figures in the light of recent events. What seems likely? Collapse, overthrow, nationalization? Maybe a balance of payments problem, maybe bodies hurled into ditches. Whatever endangers an investment.

Axton is not unusual in this regard. His American associates are all stereotypes, energetic corporate men and their lonely wives, cool and intelligent and as soulless as the risk assessments they carry out in places where dollar investments have been made. They are alternately puzzled by Greece and oblivious to it, unable to make sense of the graffiti they occasionally encounter in Athens (“Death to Fascists”) or the rant about NATO delivered to Axton by a choleric Greek man called Andreas.

What Axton and his fellow Americans are unable to see—and what the “authoritative” Library of America will not tell us either, since not a single one of its dozens of footnotes offers the necessary background—is that the Greece they are carousing in is napalm-scarred terrain, a front line in the US battle against communism ever since the Americans (and the British) turned against the Greek left after it helped them defeat Hitler’s troops. In the civil war that followed the end of Nazi occupation, it was the Greek right that received benediction from the leaders of the free world. When a military coup in 1967 put an end to any pretensions to democratic politics and led to the seven-year, torture-and-death-filled “Regime of the Colonels,” the United States backed the colonels to the hilt.

The writer Suzy Hansen, whose remarkable book Notes on a Foreign Country records her coming to terms with the hidden history of the US empire in Greece in the aftermath of 9/11, describes The Names as “a study in American ignorance.” For DeLillo, it is a convenient ignorance about an inconvenient history, an engagement with select aspects of the system but not the whole, and it is the task of his novel to set in motion a plot that will force Axton into some kind of reckoning with the world created by and for men like him.

So, although the Greeks to Axton are just backdrop—jerky caricatures carrying out the most routine of actions in inevitably comic fashion—something begins to emerge from this background of chaos. An ancient cult, seemingly of Middle Eastern origin, has appeared in Greece, murdering its victims on the basis of some arcane theology demanding that the initials of each victim’s name match those of the place they are killed. At first only a vague rumor, the cult becomes of increasing interest to Axton, with his attempts to untangle its hidden plot taking him to Jordan and, eventually, to India. The world ruled by the West still exceeds risk analysis, it seems. Underneath the spread of American business rationality lies the unnameable.

DeLillo came to write The Names after an initial period of fiction that had already highlighted what would become the key elements in his work. Six novels, from Americana (1971) to Players (1977), set out the DeLillo topos: lonely drifters colliding against massive, intricate networks ranging from the advertising industry to nuclear war. The form of the novels mimicked this binary as well, their noirish plots combining with deeply intellectual, even verbose inquiries into the mega-myths of American capitalism. Together, they established DeLillo as one of the central practitioners of what came to be known as the “systems novel”; their object of inquiry extended beyond realism’s scrutiny of individual character and social backdrop to include the often invisible but all-powerful infrastructures—media, finance, and security the most prominent among them—that dominate our lives.

The Names was a systems novel, although somewhat jaggedly so. The result of DeLillo’s own time in Athens from 1979 to 1982, it documented the rapture he felt for the Greek landscape and architecture, with its millennia-old palimpsest of human inhabitation:

The huddled uphill arrangement of whitelime boxes, the street mazes and archways, small churches with blue talc domes. Laundry hung in the walled gardens, always this sense of realized space, common objects, domestic life going on in that sculpted hush. Stairways bent around houses, disappearing.

The bravura lyricism of these descriptions makes one wish that DeLillo had written a travel book on Greece. But The Names is a novel, and it has to offer a story arc that connects its flat, modular protagonist and his banal world of “bank loans, arms credits, goods, technology” with the secretive, layered landscape. The cult of the names is DeLillo’s solution to this narrative predicament. Axton, otherwise a rational corporate man, is drawn into an obsession with the cult because it is of interest to Frank Volterra, a Hollywood filmmaker and a romantic rival in Axton’s attempts to win back Kathryn’s affection.

The terror cult, however, is never quite convincing. Is it ancient, as the novel sometimes suggests, tracing its roots all the way back to Jesus preaching in Aramaic? Or is it modern, brought into being by capitalism and empire? Are its hooded adepts fanatics from the East, or are they Americans playing out the kind of Orientalist fantasy Edward Said untangled in his work, their Lawrence of Arabia blue eyes peering out from underneath the layered turbans and hoods? DeLillo leans toward the second answer. It fits with the model of his earlier novels, and yet the three parts of The Names—travel narrative, willfully ignorant Americans, and terror cult—never quite fit together.

DeLillo would circle back to the idea of a terror cult more successfully in his later works, most tellingly in Mao II. But the novel that succeeds The Names is, in many ways, its opposite. If The Names was intended as a study of the American abroad, White Noise is a sustained examination of the American at home. From its opening pages, with a dazzling description of undergraduates transferring their belongings from their parents’ station wagons to their dorms, it is an exploration of excess:

…the stereo sets, radios, personal computers; small refrigerators and table ranges; the cartons of phonograph records and cassettes; the hairdryers and styling irons; the tennis rackets, soccer balls, hockey and lacrosse sticks, bows and arrows; the controlled substances, the birth control pills and devices; the junk food still in shopping bags—onion-and-garlic chips, nacho thins, peanut creme patties, Waffelos and Kabooms, fruit chews and toffee popcorn; the Dum-Dum pops, the Mystic mints.

This “day of the station wagons” is narrated by Jack Gladney, chair of Hitler studies at the College-on-the-Hill in the town of Blacksmith. Gladney is married to the “tall and fairly ample” Babette and has been advised by his chancellor (“tall, paunchy, ruddy, jowly, big-footed and dull”) to acquire some “badly needed bulk…an air of unhealthy excess, of padding and exaggeration, hulking massiveness.” Jack and Babette have seven children from their previous marriages and are surrounded by a surplus of media (“the National Enquirer, the National Examiner, the National Express, the Globe, the World, the Star”), hotels (“the Airport Marriott, the Downtown Travelodge, the Sheraton Inn and Conference Center”), and hardware (“People bought twenty-two-foot ladders, six kinds of sandpaper, power saws that could fell trees”). One of Jack’s ex-wives, who now calls herself Mother Devi, lives in an ashram shadowed by rumors of “sexual freedom, sexual slavery, drugs, nudity, mind control, poor hygiene, tax evasion, monkey-worship, torture, prolonged and hideous death.” When Babette teaches a posture class to the elderly at a local church, she refers to “yoga, kendo, trance-walking…Sufi dervishes, Sherpa mountaineers.” Nothing in the world, it seems, cannot be consumed and regurgitated by this form of the American dream.

The alien strangeness of Midwestern American life, full of material and media excess but shot through with existential anxiety, gave White Noise its particular allure. It was the perfect American postmodern novel, in conversation throughout with humanities departments obsessing over the relation between signifier and signified and parodying those departments—Hitler studies!—while also taking some of what they had to say seriously. All of this helped make the novel a breakthrough for DeLillo, at least in terms of reputation. His earlier novels had received critical attention, but this was the book that established him as one of the rightful heirs of the postwar American novel.

Its satirical mode, with taut comedy built out of these lives of excess, is perhaps easier to take in than the more acerbic critique that emerges from the pages of The Names. Jack and Babette are not evil people; they are sweet and hapless. Their endless appetites often seem to originate from some deep metaphysical cause as much as from something as definable as capitalism. The “white noise” of the title is the sound of technology and consumption, but it is also a postlapsarian state, endemic to the human condition rather than the consequence of political, economic, or moral choice.

This approach gives the blowback of the novel—inevitable in a DeLillo narrative—a weirdly symbolic import. For Jack and Babette, it takes the form of the fear of death, a condition widespread enough to result in an experimental drug called Dylar that might treat this fear. For the town as a whole, the blowback arrives in the form of a derailed train car releasing a toxic chemical called Nyodene Derivative. Resulting in a mass evacuation as a cloud of gas hovers over Blacksmith, the “airborne toxic event” has been seen as proof of DeLillo’s preternatural sensitivity as a novelist, foretelling in some ways the methyl isocyanate leak at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal in 1984. Of course, the Nyodene D. spill in Blacksmith is not actually a Bhopal-scale event of thousands of poor people dying in some benighted foreign country. It is instead part of the white noise of the novel, another manifestation of excess. Death and dread may haunt those affected by the event, but some Americans respond to it as first-worlders, “wrapped in shimmering rainwear…as though they’d been waiting for months to strut their stuff.” The toxic cloud itself travels over the landscape lit up by the beams of seven military helicopters “like some death ship in a Norse legend, escorted across the night by armored creatures with spiral wings.”

The writing in White Noise is wonderful, and yet the extended metaphors and the revisiting of Wagnerian-fascist mythology through the filter of Middle America can strike one as evasive. It is as though American reality, in all its excess, is too resistant to critique; only the glancing blows of satire, symbolism, or imported magic can score a point or two against it. The systems novel is itself subsumed by the system, of which publishing and readers dulled by white noise are just another aspect. After all, there is not a single reference to Bhopal or Union Carbide in the footnotes of the Library of America edition.

The distinct but twinned imperfections of The Names and White Noise make Libra’s triumph particularly satisfying. It is on a continuum with DeLillo’s previous works, even if, in choosing to write about the ur-event of postwar America, he has to double back into the early ’60s. Finally, we have something that allows DeLillo to overcome the détente between his systems novels and the system.

It isn’t entirely clear at the beginning what this new element might be. Libra’s juxtaposition of character against networked complexity suggests continuity with the previous novels. What is different is how character is approached. In place of the conventional wisdom that a focus on a single, central character offers the greatest unity, immersion, and conflict—and in contrast to his own approach in earlier works—DeLillo treats Oswald as a character best understood in juxtaposition with other characters and their stories. Instead of being focalized through a single point of view, as in The Names and White Noise, the narrative is now sliced through by multiple perspectives.

The secondary characters, a mix of actual figures and fictional creations, have a wide range. A great many are disaffected operatives of the American deep state—Walter Everett Jr., David Ferrie, Laurence Parmenter, George de Mohrenschildt, and Guy Banister—who project a combination of gentility, thuggery, and suspicion that makes for a compelling portrait of what Richard Hofstadter termed the “paranoid style” in American life. There is also Jack Ruby, the real-life Jewish nightclub owner who shot and killed Oswald, as well as the presumably fictitious Nicholas Branch, a retired CIA analyst brought back by the agency to sift through all its material and write “the secret history” of the assassination. The most affecting of these secondary characters, however, are those at the greatest remove from power, especially Oswald’s mother, Marguerite, whose voice DeLillo shapes movingly into a distinctive syntax and idiosyncratic worldview.

The multiple shifts in point of view do not result in incoherence. Instead, they offer DeLillo a purchase over his proliferating material. In a narrative whose final outcome is known to all—a dead president and a dead assassin—the story that needs to be told is that “secret history” of the winding path toward the outcome. It allows DeLillo to put together his account of how a rogue faction of the CIA, aided by Miami Cubans angered by the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, wanted to set up a fake assassination attempt on Kennedy that would implicate Fidel Castro and the Cuban intelligence services and provoke a military response from the United States. As the scheme proceeds, however, it takes on a life of its own, morphing from what was meant to look like an unsuccessful attempt with only one of Kennedy’s bodyguards injured into the actual murder of the president.

To the conspirators, Oswald is no more than a useful idiot in their complicated scheme. To history, his role is that of minor infamy, one man in a never-ending series of American “lone nut” shooters and bombers. To DeLillo, however, he is the novel’s pivotal antihero (Oswald being a Libra, the astrological sign for which is the scales of justice). A protagonist with not just one doppelgänger but a multitude of them, Oswald finally offers DeLillo a character sufficiently fragmented and manipulated for a fictional paradigm trying to grasp the misfitting puzzle pieces of a fragmented world.

Perhaps for this reason, Oswald’s life is captured brilliantly, from his troubled childhood in the Bronx (within walking distance of the house where DeLillo, three years older than Oswald, grew up) to the equally troubled stages of his adulthood—a Marine with disciplinary problems at a US Air Force base in Japan; a defector to the Soviet Union living in Minsk; a counter-defector returning to the United States with a Russian wife in tow; an abusive husband and absent father working a series of dead-end jobs in Texas and New Orleans; an anti-establishment rebel attempting to assassinate the former general and Texas right-wing politician Edwin Walker; and an aspiring defector again, this time to Cuba.

It works wonderfully, the juxtaposition of Oswald the protagonist and all the other Oswalds perceived, misunderstood, exploited, and occasionally loved by the other characters, just as Oswald’s stumbling, jittery trek through empire and home is contrasted brilliantly with the vast, merciless reach of war and surveillance—the U-2 spy planes soaring to “eighty-five thousand feet…cameras sweeping a path over a hundred miles wide”; the CIA’s radio broadcasts to the Guatemalan guerrillas fighting the United Fruit Company, which are made up of “rumors, false battle reports, meaningless codes, inflammatory speeches, orders to nonexistent rebels”; and the “one hundred and twenty-five thousand pages” on the Kennedy assassination accumulated by the FBI. The human and the inhuman are, finally, part of the same universe.

This breakthrough of form in Libra produces a stunning, dark lyricism. It is present in the passages told through Oswald’s eyes: “Crowd of about a thousand. Walker stood up there in his tall Stetson and moaned and groaned about the United Nations. Clap clap. The UN was an active element in the worldwide communist conspiracy. Clap clap. Lee slipped into a seat about midway down the aisle.” It is equally visible in other sections, a paranoid, postmodernist poetry of analogies and metaphors and allegories in the service of domination and concealment:

The Farm was known officially by the cryptonym ISOLATION. The names of places and operations were a special language in the Agency. Parmenter was interested in the way this language constantly found a deeper level, a secret level where those outside the cadre could not gain access to it. It was possible to say that the closet brotherhood in the Agency was among those who kept the crypt lists, who devised the keys and digraphs and knew the true names of operations. Camp Peary was the Farm, and the Farm was ISOLATION, and ISOLATION probably had a deeper name somewhere, in a locked safe or some computer buried deep in the ground.

The system writes its own fictions, its own secret histories, and it does so in secret languages known only to the adept. DeLillo came to understand this through his expanding body of work in the 1980s. In an American writer’s battle with an American reality that seems to exceed anything a novelist can throw at it, the novels of that decade depict an artist attempting to discover a form for his understanding. If Libra succeeds so well in this ongoing struggle, it does so by finding in its reviled, confused, and marginalized protagonist the perfect key to unlocking the mysteries of a powerful and malevolent apparatus. More than three decades later, no other American novelist has come close to achieving anything like this breakthrough.