Does my name belong to me? Does my face? What about my life? My story? Why is my name used to refer to events I had no hand in? I return to these questions again and again because others continue to profit off my identity, and my trauma, without my consent. Most recently, there is the film Stillwater, directed by Tom McCarthy and starring Matt Damon and Abigail Breslin, which was, in McCarthy’s words, “directly inspired by the Amanda Knox saga.” How did we get here?

In the fall of 2007, a British student named Meredith Kercher was studying abroad in Perugia, Italy. She moved into a little cottage with three roommates—two Italian law interns, and an American girl. Less than two months into her stay, a young man named Rudy Guede, an immigrant from the Ivory Coast, broke into the apartment and found Meredith alone. Guede had a history of breaking and entering. A week prior, he had been arrested in Milan while burglarizing a nursery school, and was found carrying a 16-inch knife. He was released. A week later, he raped Meredith and stabbed her in the throat, killing her. In the process, he left his DNA in Meredith’s body and throughout the crime scene. He left his fingerprints and footprints in her blood. He fled to Germany immediately afterward, and later admitted to being at the scene.

I am the American girl in that story, and if the Italian authorities had been more competent, I would have been nothing more than a footnote in a tragic story. But as in many wrongful convictions, the authorities formed a theory before the forensic evidence came in, and when that evidence indicated a sole perpetrator, Guede, ego and reputation led them to contort their theory to maintain that I was still somehow involved. Guede was quietly convicted for participating in the murder in a separate fast-track trial, and then I became the main event for eight long years.

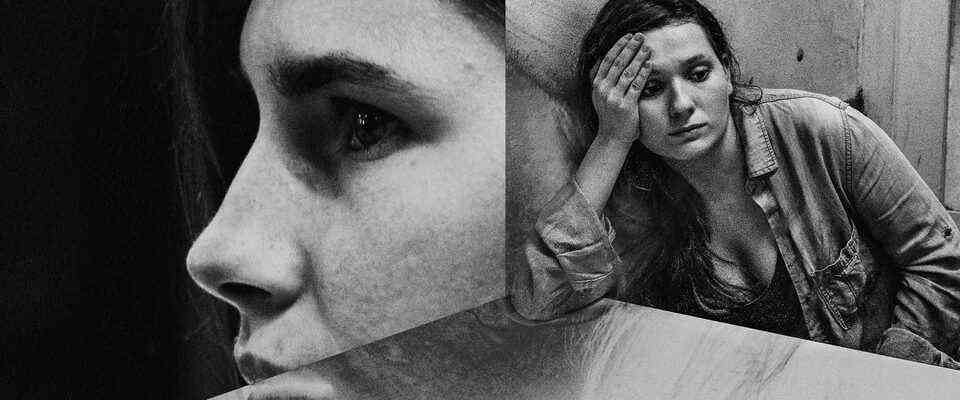

While I was on trial for the murder of Meredith Kercher, from 2007 to 2015, the prosecution and the media crafted a story, and a doppelgänger version of me, onto which people could affix all their uncertainties, fears, and moral judgments. People liked that story: the psychotic man-eater, the dirty ice queen, Foxy Knoxy. A jury convicted my doppelgänger, and sentenced her to 26 years in prison. But the guards couldn’t handcuff that invented person. They couldn’t escort that fiction into a cell. That was me, the real me, who returned to that windowless prison van, to those high cement walls topped with barbed wire, to those cold, echoing hallways and barred windows, to that all-consuming loneliness.

Ten years ago, at the age of 24, I was acquitted, and I tumbled into a kind of purgatory. I left one cell and immediately entered another: the quiet of my childhood bedroom. Outside, the telephoto lenses were fixed on my closed blinds. Prison had given me an appreciation for all the freedoms I’d taken for granted. Freedom showed me how many I still lacked.

As I walked back into the free world, I knew that my doppelgänger was there alongside me. I knew that everyone I would ever meet from then on would have already met, and judged, her. I had been acquitted in a court of law, but sentenced to life by the court of public opinion as, if not a killer, then at least a slut, or a nutcase, or a tabloid celebrity. Why doesn’t she just go away already? Her 15 minutes are over.

In freedom, I had become a pariah. Looking for work, going back to school, buying tampons at the pharmacy, everywhere I went I met people who already thought they knew who I was, what I’d done or not done, and what I deserved. I was threatened with abduction and torture in broad daylight; I was threatened with having Meredith’s name carved into my body. Strangers sent me lingerie and bizarre love letters. All over the world, people believed they knew me, a warped assumption that turned me into a monster to some and a saint to others. I felt like I was always standing behind that cardboard cutout, Foxy Knoxy, saying, Hey, back here, the real me! Even most of the strangers who offered kindness and support didn’t truly see me. They loved her.

It’s hard to make friends, to date, to be a regular person when everyone you meet has a preconceived notion of who you really are, whether positive or negative. I could have chosen to hide out, to change my name, to dye my hair, and hope no one recognized me ever again. Instead, I decided to embrace the world that had dehumanized me, and all those who turned me into a product.

From the moment I was arrested, my name and face and trauma became a source of profit for news organizations, filmmakers, and other artists, scrupulous and unscrupulous. The most intimate details of my life, from my sexual history to my thoughts of death and suicide in prison, were taken from my private diary and leaked to journalists. Those journalists turned my darkest fears into fodder for hundreds of articles, thousands of blog posts, and millions of hot takes. People speculated about my mental state and sexuality, they diagnosed me from afar, they used my predicament as a metaphor, they made TV movies about me, based characters in legal shows on me, and the worst of them took every opportunity they could, while I was in prison and while I’ve been out, to shame me for something I didn’t do, to shame me for living while Meredith is dead, to shame me for being in the very headlines they write, for being in the photographs they take without my consent. The hypocrisy and the cruelty are maddening. And yet, being under that microscope has given me insight into how wrong a media narrative can be, how easy it is for all of us to consume other people’s lives as if they were mere content to fill up our Twitter feeds.

All of this has led me to dedicate myself, in my written journalism and on my podcast, Labyrinths, to upholding the ethical principles I so often found lacking in the media that covered and consumed me. I believe that journalists must always center people in their own stories, and recognize what is at stake for their subjects. But even as I put my own voice into the world, the idea of me is still an object for others to consume. So I can’t say I was surprised when I heard about Tom McCarthy’s new film.

Stillwater is both “loosely based on” and “directly inspired by” the “Amanda Knox saga,” as Vanity Fair put it in an article published by a for-profit magazine company promoting a for-profit film, neither of which I am affiliated with. I want to pause on that phrase, “the Amanda Knox saga,” because the manifold ways that my identity continues to be exploited start with this shorthand. What does “the Amanda Knox saga” refer to? Does it refer to anything I did? No. It refers to the events that resulted from the murder of Meredith Kercher by Rudy Guede. It refers to the shoddy police work, the flawed forensics, and the confirmation bias and tunnel vision of the Italian authorities whose refusal to admit their mistakes led them to wrongfully convict me, twice. In those four years of wrongful imprisonment and eight years of trial, I had near-zero agency.

Everyone else in that “saga” had more influence over the course of events than I did. The erroneous focus on me by the police led to an erroneous focus on me by the press, which shaped how I was presented to the world, and continues to shape how people treat me today. In prison, I had no control over my public identity, no voice in my own story.

This focus on me led many to complain that Meredith Kercher had been forgotten. But whom did they blame for that? Not the Italian authorities. Not the press. Somehow it was my fault that the police and media focused on me at Meredith’s expense. The result of this is that 14 years later, my name is the name associated with this tragic series of events I had no control over. Meredith’s name is often left out, as is Rudy Guede’s. When he was released from prison in late 2020, the New York Post headline read: “Man Who Killed Amanda Knox’s Roommate Freed on Community Service.” My name is the only name that shouldn’t be in that headline.

In light of the #MeToo movement, more people are coming to understand how power dynamics shape a story. Who had the power in the relationship between Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky, the president or the intern? Shorthand matters. Calling that event “the Lewinsky scandal” fails to acknowledge the vast power differential, and I’m glad that more people are now referring to it as “the Clinton affair,” which explicitly calls out the person with the most agency in that series of events. I would love nothing more than for people to refer to the events in Perugia as “the murder of Meredith Kercher by Rudy Guede,” which would make me the peripheral figure I always was, the innocent roommate.

But I know that my wrongful convictions, and my trials, became the story that people obsessed over. I know they’re going to call it “the Amanda Knox saga” in perpetuity. I can’t change that, but I can ask that when people refer to these events, they make an effort to understand that how you talk about a crime affects the people involved: Meredith’s family, my family, my co-defendant, Raffaele Sollecito, and me.

Every review of Stillwater I have seen has mentioned me, for better or worse. Some refer to me as a person convicted of murder, while conveniently leaving out the fact of my definitive acquittal. The New York Times, in profiling Matt Damon, referred to these events as “the sordid Amanda Knox saga.” That’s not a great adjective to have placed next to your name, especially when it describes events that you didn’t cause, but that you suffered from.

Even the tiniest choices people make about how to refer to newsworthy events shape how they are perceived. And when real events serve as inspiration for fiction, that effect can be magnified and distorted. Stillwater is by no means the first project to use my story without my consent, and at the expense of my reputation. While I was still in prison, and still on trial, Lifetime produced a film called Murder on Trial in Italy. I sued the network, which resulted in it cutting from the film a dream sequence that depicted me killing Meredith. A few years ago, there was the Fox series Proven Innocent, starring Kelsey Grammer, which was developed and described as “What if Amanda Knox became a lawyer?” The first time I heard from the show’s makers was when they had the audacity to ask me to help them promote it on the eve of its premiere.

My name, my face, my story have effectively entered the public imagination. I am legally considered a public figure, and that leaves me little recourse to combat depictions of me that are harmful and untrue, and gives carte blanche to anyone who wants to write about me to do so without consulting me in any way. A prime example is Malcolm Gladwell’s book Talking to Strangers, which features a whole chapter analyzing my case. He reached out to me just before publication to ask if he could use excerpts of my audiobook in his audiobook. He didn’t think to ask for an interview before forming his conclusions about me. I allowed him to use my voice, because at least Gladwell was arguing for my innocence. But even he put the burden of my wrongful conviction on me, based on my behavior, rather than on the authorities, who held all the power in that dynamic. To his credit, Gladwell responded to my critiques over email, and was gracious enough to join me on my podcast. I have extended the same invitation to Tom McCarthy and Matt Damon.

McCarthy was “inspired by” my story, and told Vanity Fair that “he couldn’t help but imagine how it would feel to be in Knox’s shoes.” But that didn’t inspire him to ask me how it felt to be in my shoes. He became interested in the family dynamics: “Who are the people that are visiting [her], and what are those relationships? Like, what’s the story around the story?” My family and I have a lot to say about that, and would have happily told McCarthy if he’d ever bothered to ask. McCarthy has no legal obligation to do so. And he is, after all, telling a fictional tale. But legal mandates are not the same as moral or ethical ones.

“We decided, ‘Hey, let’s leave the Amanda Knox case behind,’” McCarthy told Vanity Fair. “But let me take this piece of the story—an American woman studying abroad involved in some kind of sensational crime and she ends up in jail—and fictionalize everything around it.” But that story, my story, is not about an American woman studying abroad “involved in some kind of sensational crime.” It’s about an American woman not involved in a sensational crime, and yet wrongfully convicted of committing that crime. It’s an important distinction. Now, if he truly were leaving the Amanda Knox case behind, that shouldn’t matter. But then why does every review of Stillwater mention me? Why do photos of my face, not owned by me, appear in articles about the film?

Clearly, McCarthy has not left the case behind. Which means that how he has chosen to fictionalize my story affects my reputation. I was accused of being involved in a death orgy, a sex game gone wrong, when I was nothing but platonic friends with Meredith. But the fictionalized version of me in Stillwater does have a sexual relationship with her murdered roommate. In the film, the character based on me gives a tip to her father to help find the man who really killed her friend. Matt Damon tracks him down. This fictionalizing erases the corruption and ineptitude of the authorities. Truth is stranger than fiction here: In reality, the authorities already had the killer in custody. Rudy Guede was convicted before my trial even began. They didn’t need to find him. And even so, they pressed on in prosecuting me, because they didn’t want to admit they had been wrong.

Vanity Fair reported that “Stillwater’s ending was inspired not by the outcome of Knox’s case, but by the demands of the script [McCarthy] and his collaborators had created.” I read a sentence like that, and I immediately wonder: Is the character based on me actually innocent in McCarthy’s film?

It turns out, she asked the killer to help her get rid of her roommate. But she didn’t mean it that way. She wanted her roommate evicted, not killed. Her request indirectly led to a murder. Did McCarthy consider how that creative choice affects me? I continue to be accused of knowing something I’m not revealing, of having been involved somehow, even if I didn’t plunge the knife.

By fictionalizing away my innocence, by erasing the role of the authorities in my wrongful conviction, McCarthy reinforces an image of me as guilty. And with Damon’s star power, both are sure to profit handsomely off this imagined version of “the Amanda Knox saga” that will leave plenty of viewers wondering, Maybe the real-life Amanda was involved somehow, and Googling whether the film’s story is true.

I never asked to become a public person. The Italian authorities and global media made that choice for me. And when I was acquitted and freed, the media and the public wouldn’t allow me to become a private citizen again. I have not been allowed to return to the relative anonymity I had before Perugia. I have no choice but to accept the fact that I live in a world where my life, and my reputation, are freely available for distortion by a voracious content mill.

I’m not angry with Matt Damon or Tom McCarthy, but I am disappointed that they didn’t seem to appreciate the value of my perspective and voice, only the value of my circumstances as inspiration and my name as a marketing tool. For four years, I lived alongside women actually guilty of crimes ranging from petty theft to filicide. And let me tell you, playing cards with a drug dealer and being taught to roll out pizza dough with a broomstick by a mafiosa certainly puts things in a new perspective—one that doesn’t excuse people’s crimes, but puts them into context. I came to recognize the humanity in my fellow inmates, imperfect people whom society had written off as worse than worthless, or as monsters. Those same judgments were, and still are, hurled at me, despite my innocence.

All of this has made me extremely skeptical of those who easily pass judgment. It has made me allergic to the impulse to flatten others into cardboard, to erase their human complexity, to rage against things about which I know only a snippet. Judgment only gets in the way of understanding. Refraining from judgment has become a way of life for me. Call it radical empathy, or extreme benefit of the doubt. I know how wrong people were about me, and I don’t ever want to be that wrong about another person. The world is not filled with monsters and heroes; it’s filled with people, and people are extraordinarily complex. That includes Tom McCarthy and Matt Damon. I’m sure they had no ill intent. That, too, matters.

.