November 8, 2023, reading time: 4 minutes.

Photo evidence: A research team has observed for the first time how two different viruses attach to each other and combine. Until now, such a form of contact between different viruses was not known. As genetic analyzes have shown, these bacteriophages help each other to infect a host cell and multiply. It is the first evidence of this type of relationship between viruses, the team reports. However, the interaction mechanism could be more widespread than thought.

As is well known, viruses need a host organism in order to reproduce. This could be, for example, a human cell or, in the case of bacteriophages, a bacterium. “Some viruses, so-called satellites, also rely on another virus, a ‘helper’, to complete their life cycle,” explains senior author Ivan Erill from the University of Maryland. The satellite virus therefore needs the helper either to build its protective shell, which encloses the virus’s genetic material, or to help it replicate its DNA.

For this to happen, the satellite virus and the helper virus must be at least temporarily close to each other. However, so far there is no known evidence of a satellite actually binding itself to a helper.

First image of satellite-helper binding

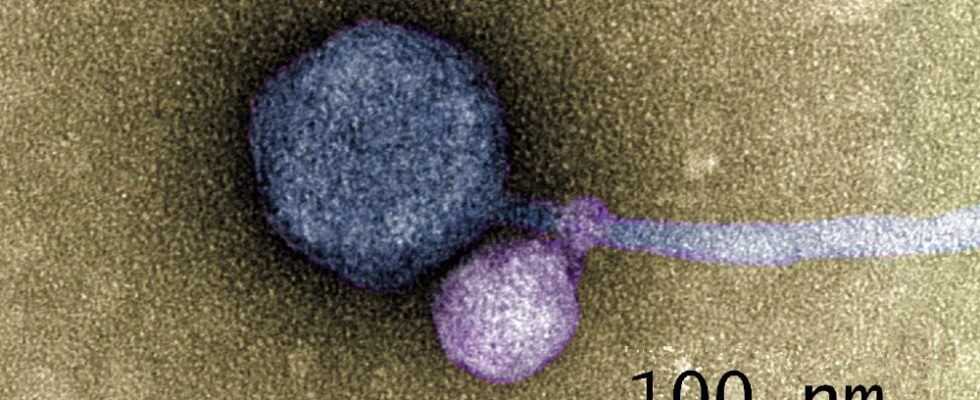

The research team led by Tagide deCarvalho from the University of Maryland has now managed to capture detailed images of such satellite helper contacts for the first time. To do this, the researchers used a transmission electron microscope (TEM) to observe samples of bacteriophages that infect bacteria of the genus Streptomyces and whose genetic analyzes had previously revealed discrepancies.

The images showed that 40 out of 50 helper viruses were not present individually, but were connected to a satellite virus. “When I saw it, I couldn’t believe it,” says deCarvalho. “No one has ever seen a bacteriophage or any other virus attach to another virus before.”

As the team observed, the satellite bacteriophages attached their “tail” to the “neck” of a helper bacteriophage – the connecting piece between the “head” containing the genetic material and the tail of the virus. In some individual helper viruses, there were also remnants of tail proteins of the satellites on the neck, which the researchers describe as “bite marks”. Also striking: the satellite viruses were never directly bound to their bacterial host cell in the images, but only indirectly via the helper virus.

What is the virus double pack used for?

But what purpose does this coupling of viruses serve? To learn more about viral interaction, the scientists sequenced the genomes of the satellite viruses, helper viruses and host cells. They found genes in the satellite viruses for their protective shells, but not for their replication. It is fitting that these satellite viruses rely on the cell machinery of their bacterial hosts to reproduce.

For this to work, the satellite viruses have to insert their own genetic material into that of the bacterial cell. This is usually ensured by a special gene in the virus, which is also present in already known satellite viruses and in some of the newly examined satellites, which do not require direct contact with their helper viruses. However, the satellite can only reproduce if a helper virus enters the host cell and brings additional genetic information with it.

Help for co-infection

However, this is apparently different with the satellite viruses that have now been discovered and are attached to their helpers. As deCarvalho and her colleagues discovered, these satellites, dubbed “MiniFlayers,” lack the integration gene to insert their genetic material into that of the host. That is why these satellite viruses are absolutely dependent on the simultaneous presence of the helper viruses in the host – without its genetic help, they cannot infiltrate the host genome.

“Attachment now makes perfect sense,” says Erill, “because how else can the viruses guarantee that they enter the cell at the same time?” This fits with the researchers’ observation that these MiniFlayer satellite viruses have specialized tail components consisting of fibrous proteins, with which they can bind to the helper phages. The researchers explain that this could ensure co-infection through simultaneous entry into the host. However, direct evidence for this explanation is still missing.

A widespread phenomenon?

The researchers also used bioinformatics methods to investigate the evolutionary development of these viruses. The analyzes revealed that the MiniFlayer satellite viruses and their helper viruses have evolved together for a long time. “This satellite has been tuning in for at least 100 million years and has optimized its genome so that it is associated with the helper,” says Erill. This suggests that there may be many more cases of this type of relationship between viruses.

“It’s possible that many of the bacteriophage samples that were thought to be contaminated were actually these satellite helper systems,” says deCarvalho. Their analyzes also began with a supposedly contaminated genetic analysis of a bacteriophage, which the researchers then got to the bottom of. Future work could examine in more detail how common this phenomenon is and how the satellite connects to the helper. (ISME Journal, 2023; doi: 10.1038/s41396-023-01548-0)

Source: University of Maryland

November 8, 2023 – Claudia Krapp