The EU Commission wants the international community to cut almost all emissions by 2040. But how realistic is that if the members are already failing to meet the goals for 2030?

Climate neutral in 2050: This is the green dream of the European Union. More than a quarter of a century remains until then. However, time is relative and flies quickly when there is a lot to do. This should also apply to the community of states. She wants to move away from coal, oil and gas. Fossil fuels should be replaced by renewable energy sources and CO2 emissions should be massively reduced. But it doesn’t work equally well everywhere. Things are going according to plan for some EU members, and two have already exceeded the requirements. However, many others are crawling towards their climate goals at a snail’s pace.

But that didn’t stop the EU Commission from recently coming up with a new interim target: In 2040, the international community should release 90 percent less carbon compared to emissions in 1990. The new recommendation is ambitious. Because it is already clear that the EU will miss its interim target for 2030. CO2 emissions should actually fall by at least 55 percent by then. According to the current status, 51 percent is realistic.

“Even if the EU is very successful in reducing CO2 emissions compared to other countries, this gap in ambition cannot simply be closed,” says Felix Schenuit, who works at the German Institute for International Politics and Security at the Science and Politics Foundation (SWP ) researches, among other things, European climate policy.

The EU has its goals in mind – but not the path to get there

The reasons for this partly lie in Brussels: the interim target for 2040 is currently still a recommendation. It could only be enshrined in law after the European elections, which are due in June. Whether the current proposal will remain is at least as unclear as the answer to how Parliament and the Commission will be composed in the future. After the elections, it could well happen that the new Commission in Brussels changes the climate plans. Parliament and member states must then vote on the proposals in the legislative process. The political scientist explains that it will probably take until next year before the goals are legally anchored.

In the end, it’s not just the percentage that matters, “but also the instruments so that emissions are really reduced.” Brussels is still shying away from setting binding guidelines on the path to climate neutrality. But it won’t work without it, especially since current tools such as emissions trading are not sufficient for countries to meet the 2030 requirements. The instruments still need to be expanded for 2040.

“In these technical negotiations there is also an argument about which sector has to contribute how much,” says climate policy expert Schenuit. In the future, the EU Commission sees industry and agriculture in particular as having a responsibility. In the opinion of several EU parliamentarians, the latter in particular has so far been treated too gently when it comes to climate protection. That should change in the future, it was recently said from Brussels. How exactly is still being negotiated.

Eastern Europe is reducing emissions faster than its western neighbors

However, the requirements for the individual EU member states are more specific. In order to be climate neutral by 2045, Germany would have to reduce its greenhouse gases by 65 percent by 2030 and by 88 percent by 2040. To achieve this, the federal government is planning to phase out coal by 2030, bringing it forward by eight years. However, it is still unclear whether this will be successful. At the same time, the traffic light coalition in Berlin launched a climate protection program and is supporting the steel industry, one of the most climate-damaging sectors, on the path to green (read more about this here).

Germany is the leader among the countries with the highest CO2 emissions. The Federal Republic blew more than 764 million tons into the atmosphere in 2021, data from the European Environment Agency show. According to this, France, Italy and Poland are among the EU’s biggest climate sinners, each with a carbon equivalent of over 300 million tons. Together, the four countries cause more than 50 percent of European emissions. The main driver is the energy sector, according to the EU Commission.

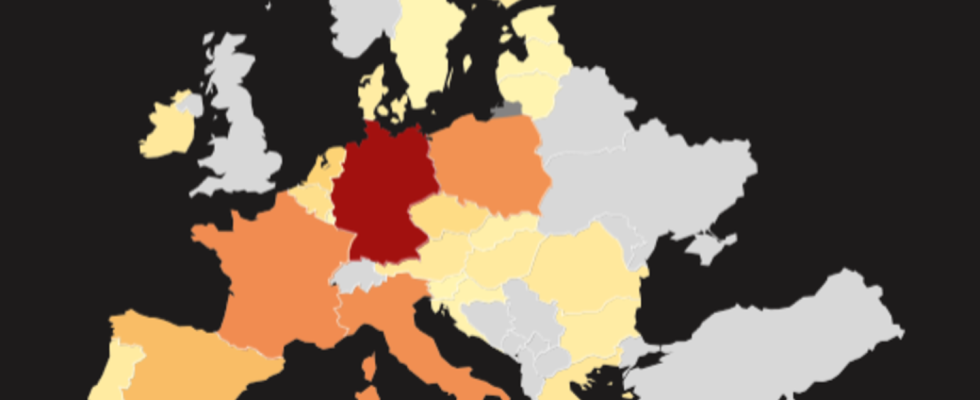

However, Europe’s biggest climate polluters are on the road to recovery. Germany reduced its emissions by 41 percent in 2021 compared to 1990. The European leader is Sweden, which exceeded its target of 63 percent by 13 percent. With savings of 44 percent, the Czech Republic is also above the target actually set for 2030. In a pan-European comparison, the data from the European Environment Agency show that the eastern countries in particular – apart from Poland – are on the right track, while the gap to the target is increasing Western states are getting bigger and bigger.

“Overall, the Member States’ targets do not currently indicate that anything is accelerating,” emphasizes Schenuit.

According to the data, four countries have even increased their emissions: Cyprus was actually supposed to reduce its CO2 emissions by 30 percent by 2030, but so far it has more than doubled compared to 1990. He is followed by Ireland, where emissions in 2021 were twelve percent higher than in 1990. According to the Irish environmental authorities, the energy sector in particular is driving up the amount of greenhouse gases. The country covers 90 percent of its needs by importing fossil energy. Green technology projects do exist, but companies rarely sign government contracts, meaning renewables in Ireland are rarely subsidized and prices remain high.

The data from Finland are most surprising: emissions there are six percent above the 1990 value. This is significantly lower than in Cyprus and Ireland, but for a country that is already ahead of all other EU states, namely by 2035. Wanting to be climate neutral is astonishing. When it comes to energy, Finland relies on nuclear power and, since the oil crisis of the 1970s, also on peat as a fuel, which is at least as harmful to the climate as coal. The raw material is also problematic because it is obtained from moors, which actually serve as natural CO2 storage. Since the 1950s, Finland has drained more than half of its peatlands. Researchers at the Natural Resource Institute advocate restoring the areas and also ending subsidies for wood processing. Since Finland stopped importing wood from Russia, the country has increasingly been clearing its own forests itself.

How does the Commission still want to achieve the goals?

It is currently almost certain that the EU will miss its 2030 climate target. Schenuit says that it will also be expensive for some member states. Anyone who cannot comply with the requirements must now compensate for their failures with emissions certificates. Trade has so far been carried out between two countries. But how is the system supposed to work if more states than expected cannot meet their goals? The Austrian newspaper “Standard” reports that there is already discussion in Brussels about whether emissions trading should be opened up to third countries if the certificates in the EU area run out. Then, for example, Germany could not only buy emissions certificates from Sweden, but also from the USA or India. Alternatively, proceedings for breaches of contract against the EU states are also possible, the newspaper reports.

However, Schenuit believes it is likely that some member states will insist on softer rules and requirements after the EU elections. Even if a lot is still uncertain, one thing is clear: “If the member states do not stick to the targets, this could quickly become a problem.”

The EU Commission is also toying with a technology to permanently store CO2. In Germany, however, the so-called Carbon Capture and Storage (CSS) is controversial. Carbon that is produced in industrial plants or when burning fossil fuels should be stored underground. However, critics complain that CCS technology leaves a back door open for fossil energies and slows down the expansion of renewables.

“Various scientific scenarios show that we will not be able to survive without this technology in the long term,” emphasizes Schenuit.

In his opinion, it could take until 2040 before it can be used extensively – exactly when the EU countries should have already saved the majority of their emissions.

Sources: European Environment Agency, Ministry of Environment Finland, European Commission, European ParliamentFederal Environment Agency, International Energy Agency (IEA), Heinrich Böll Foundation, Natural Resources Institute Finland“Irish Times“, “The standard“, Environmental Protection AgencyUnited Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, DPA