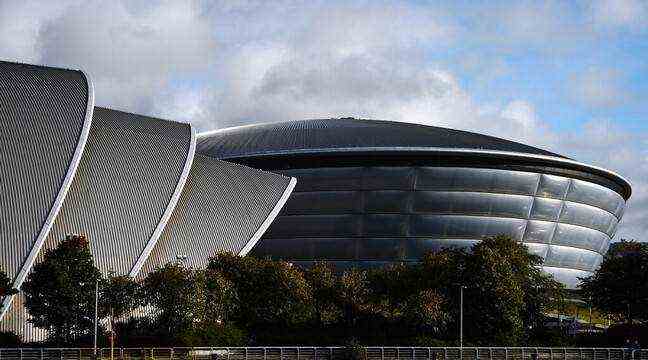

COP26 opens this Sunday at

Glasgow only to fall the curtain a fortnight later, Friday, November 12. At least without counting possible extensions, which the COPs are familiar with.

Seen from the outside, these diplomatic high masses on the issue of climate change may seem obscure. 20 minutes therefore helps you to see more clearly by explaining the major challenges of this COP26 and the context in which it opens.

What exactly are the COPs?

The COPs are the Conferences of the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNCAC). This treaty was adopted during

Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, 1992. It takes up the main principles of the final declaration of this summit and is to be seen as a first call to engage in the fight against climate change. This UNCAC entered into force in March 1994. To date, 197 States (196 as well as the European Union) have ratified it. These countries are called the “parties” to the Convention.

The COPs are therefore the annual meetings of these 197 parties, the objective of which is to verify the correct application of the objectives adopted within the framework of the UNCAC. The first COP took place in Berlin in 1995. The one that opens in Glasgow will therefore be the twenty-sixth.

Where are we today in these COPs?

Among the 25 COPs that have already taken place, one is to be engraved more than the others in stone. It’s here COP21 in Paris, in 2015. It resulted in the Paris Climate Agreement, the first binding agreement on climate change bringing together all Nations. Ratified to date by 191 parties to the UNCAC, this agreement sets the goal of keeping the increase in the average temperature of the planet well below 2 ° C compared to pre-industrial levels. And preferably even limit this increase to 1.5 ° C.

Since 2015, global annual greenhouse gas emissions (CO2, methane and nitrous oxide for the three main ones) have continued to grow despite everything. Up to 59.1 billion tonnes in 2019, according to

the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). This is 2.6% more than in 2018. For 2021, these emissions should be close to 60 billion tonnes,

UNEP anticipated on Tuesday.

Why does COP26 mark the end of a first cycle?

“A key point of the Paris Agreement is that it is dynamic, organized in a five-year cycle, at the end of which the States are supposed to gradually revise their ambitions in terms of GHG reduction”, explains Henri Waisman, researcher at of the climate program of the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (Iddri).

These ambitions and the roadmap to achieve them must be formalized in Nationally Determined Contributions. These NDCs are those plans in which each state stipulates the reductions in GHG emissions it aims for in the short term. [horizon 2030]. The Paris agreement having been signed at the end of 2015, the 191 parties had until the end of 2020 and the COP26 in Glasgow – which was initially to be held on that date – to file their NDCs, or revise them upwards for those who do. had already submitted one in 2015.

The Covid-19 gave them an additional one-year delay. But it is still lacking. As of October 12, the UNCAC said it had received 116 NDCs from 143 countries. A figure that continues to change as COP26 approaches. Long awaited, the determined national contribution of China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, fell on Thursday afternoon. Still others could be published by the opening of the COP,

on the sidelines of the G20, in particular, which opens this Saturday in Rome.

But the stake is not only to have the 191 NDC as soon as possible. The quality of the plans transmitted is equally important. Both IDDRI and the Climate Action Network point to insufficient NDCs or even going backwards compared to those of 2015 in the copies already transmitted. This is the case of Russia, Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia or Australia, lists the RAC. For its part, UNEP warned on Tuesday about a general lack of ambition on the part of States in the commitments made to date, far from leading us on the path limiting global warming to + 2 ° C.

And apart from the question of ambition?

In Glasgow, states will once again have to look at the “rulebook”, the manual for the application of the Paris agreement that still remains to be finalized. “Many points of this” rulebook “were sealed during the COP24 in Katowice,” recalls Lola Vallejo, director of the climate program at IDDRI. But there are still points of disagreement. “One is that of transparency,” says Aurore Mathieu, responsible for “international policies” at the Climate Action Network (RAC), a federation of French NGOs. We are now entering a new cycle of the Paris Agreement, in which countries will have to implement the commitments made in their NDC. It is therefore necessary that the countries agree on a common timetable to regularly take stock of the progress made towards achieving their objectives, as well as on common reporting rules, which are both standardized and transparent. “

This is a first file that this COP26 must finalize. Aurore Mathieu and Lola Vallejo add a second, more complex and dragging on: Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. This provides for mechanisms authorizing States to trade GHG emission rights: those who emit too much buy from those who emit less. In other words, this article 6 aims to provide a regulatory framework for a future carbon market between States. “It is capital, because it has the potential to be an effective GHG reduction tool if it is well put together, but will have the opposite effect otherwise”, insists Aurore Mathieu. States are fretting in particular on an accounting question: who, the country which buys the emission reduction or the one which sells it, will be able to add it to its carbon footprint? Counting it twice cannot be an option, at the risk of suggesting that emissions are dropping faster than reality.

What about the 100 billion promise?

It will once again be the backdrop to this COP26. As a reminder, this promise is the one formulated at the COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009 by the rich countries. They pledged to mobilize 100 billion dollars per year, by 2020, to help the countries of the South to cope with climate change. Twelve years later, the account is not there. a

OECD mid-September report estimated the funds mobilized in 2019 by the countries of the North at 79 billion. “70% of funds granted in the form of loans to countries which are already facing an increase in their debts,” specifies Aurore Mathieu. The majority of these funds also go to GHG reduction projects and much less to adaptation projects to the already real impacts of climate change, when the Paris agreement requires a balance between the two. “

This broken promise pollutes North-South relations on climate issues. “And does not help either on the question of ambition, insists Aurore Mathieu. For many countries, being able to put in place actions to reduce their GHG emissions depends precisely on the financial flows they are supposed to receive from rich and developed countries. “