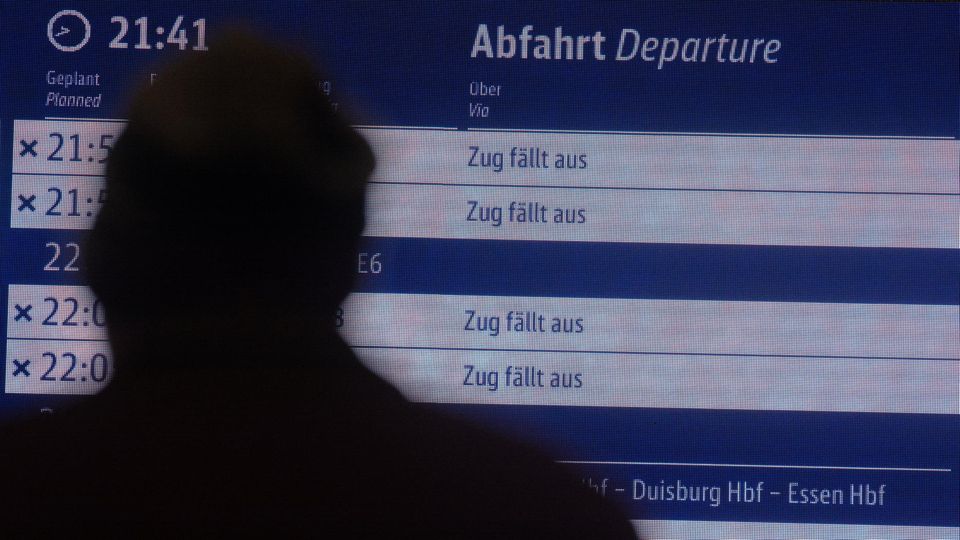

His train strike is incredibly annoying. He has a notoriously bad mood. And then Claus Weselsky sat through the “Tagesschau” every evening. Nevertheless, a rescue of honor is now due for the head of the train drivers’ union.

Many people are cursing the head of the train drivers’ union these days. The railway board members anyway, but also numerous business travelers or commuters who have to reach their destination crammed into buses and trains. I know what it feels like, standing for three quarters of an hour, cheek to cheek on the Berlin public transport bus.

The only question is: what does it all mean? Quite simply: that Weselsky does a damn good job. Because that is his job: representing the interests of the employees for whom he is the union boss. Yes, the strike is annoying and it is expensive: clever economists have calculated that the German economy is losing 100 million euros per day. But, with all due respect: that is exactly the point of the event! A strike that doesn’t hurt isn’t a strike.

Where is it now, the beautiful German “social partnership” in which we have supposedly been snuggled up so comfortably for the last few decades? Are the good Germans now becoming the new French after the farmers’ protests and in the middle of the railway strike?

A highly hypocritical construct

Strictly speaking, “social partnership” has always been a highly hypocritical construct. It’s not primarily about “partnership” – but about distribution conflicts. Some want to keep labor costs as low as possible, for example for a greater return on investment; the others want more wages or salaries, for example to pay their rent – so both want more of the same pie. Seen this way, there can be no “partnership”. Even Mr. Weselsky can’t change that – even if he came across as “woke”.

Let’s call it all: social struggles. Because that’s what they are. Weselsky is fighting this battle. It is the last big one of his life. And through his appearance he tears the veil of lying rhetoric off the entire event. “We’re all in the same boat, aren’t we?” No, we are not all in the same boat. The employees of a company (here: the train drivers) have different interests than the owners of the company (here: the federal government).

Others would also have a turn? Others can only look with envy at the train drivers because they have no collective agreement, perhaps not even a works council, and are fobbed off with low wages? That’s true – but why should one misery justify another? Should the train drivers be good so that in the end everyone has the same amount, namely: the same little? That would be socialism – at the lowest level. One that even the most greedy capitalist could get excited about.

Weselsky’s fight can also help others

Something else would be called for now: that collective agreements finally become standard again, especially in East Germany. And that companies cannot avoid setting up works councils. Seen this way, Weselsky is fighting a battle that could also benefit other industries. He shows that the labor market is fundamentally reorganizing. In times of demographic change, many companies are desperately looking for workers. Anyone who treats them badly will not find any in the future. The balance of power between labor and capital is shifting in favor of labor. This doesn’t just apply to the railways, which already have too few train drivers.

Weselsky makes it clear: Now the turbo-liberalization and the disenfranchisement of employees are over. People who toil in the Amazon warehouse, who rush around as parcel delivery people or who sit at the checkout at Lidl have understanding for the train drivers’ union much more often than you would think. Because they know that the train drivers are fighting a battle that they may not be able to fight now, but that they may face in the future.

A union leader is not a supplicant

And the rhetoric of the GdL boss? Well, he has also described railway managers as “rivets in pinstripes”, “liars” or “full-headed people”. But should a union leader come across as understanding in his negotiations? I feel you – but I would like a little more money for my people. Just a tiny bit. Hey, can we talk about that? Would that be ok for you?

No, Mr. Weselsky is a union leader, not a supplicant! Salaries and working conditions are not begged for, they are demanded. Whether they can be enforced is another matter entirely. But has there ever been an employer on this planet who said, “Oh, it’s great that you came. We’ve been wanting to talk to you about raising your salary for a long time?” It still has to be invented.

Higher salaries? Never fit into the landscape

Instead, employees like to be given the most beautiful management poetry – do you actually learn that at all those management seminars to which the higher-ups like to retreat for days, preferably in seminar hotels with a wellness oasis? “Unfortunately things are really bad at the moment, but we know that this is an important issue for you.” – “We have this on our radar.” – “You know, the difficult market environment.” Or, more popularly: “The transformation now demands all of our strength from all of us.”

Somehow it’s always really bad. Somehow it never “fits into the landscape”. Mr. Weselsky doesn’t want to wait for his demands to “fit into the landscape.” And that’s a pretty good thing.

No landlord says to the tenant: I will waive the rent for the next three months because times are so hard for you. No energy company is lowering prices because people no longer know how to pay for electricity and gas. Everyone gets their bills and everyone has to pay them – including the train drivers. The whole thing is also called: capitalism. And as long as that is the case, we expect Weselsky, of all people, not to stick to these rules but to practice modesty?

The five-day week also had to be fought for

French conditions? Everything that the workers’ movement achieved in Germany was fought for. For example, the five-day week with Saturday off. The accompanying campaign will never be forgotten: “Saturday is Dad’s mine!” Or continued payment of wages in the event of illness also for workers, not just for employees. To this end, the metal workers went on strike across northern Germany on October 24, 1956. Strikebreakers? Received a warm ear from the workforce in front of the factory gate. The solidarity lasted. Continued payment of wages was enforced. It was the longest and most extensive strike in the history of the German trade union movement: 114 days, 16 weeks. A bit more than the six days now at the GdL, right?

“There are too few strikes in this country.”

And as far as rhetoric is concerned: please no false, hypocritical sensibilities. There was once a union boss, Detlef Hensche, who had a completely different approach. He was head of IG Druck und Papier (yes, there used to be something like that!). In 1976, at the big May Day rally in Frankfurt am Main, he made it clear where the hammer was: “If the capitalists want a power struggle,” said Hensche, “the unions have to fight back.” By the way, Hensche just died. Not without a certain melancholy of old age, he finally looked back on the great struggles of his life and stated: “There are too few strikes in this country.”

So, dear Mr. Weselsky, don’t be misled. You are not a “power-drunk union boss who loves the big show,” as “Spiegel” writes (although you do enjoy the show a bit, right?). They represent the interests of those people who sit at the front of the train and – hopefully soon again – take us safely to our destination, day and night. And you do that job pretty well.

With this in mind: Forward, Mr. Weselsky! And don’t forget what your strength is! Namely, that you don’t want to be liked by everyone.