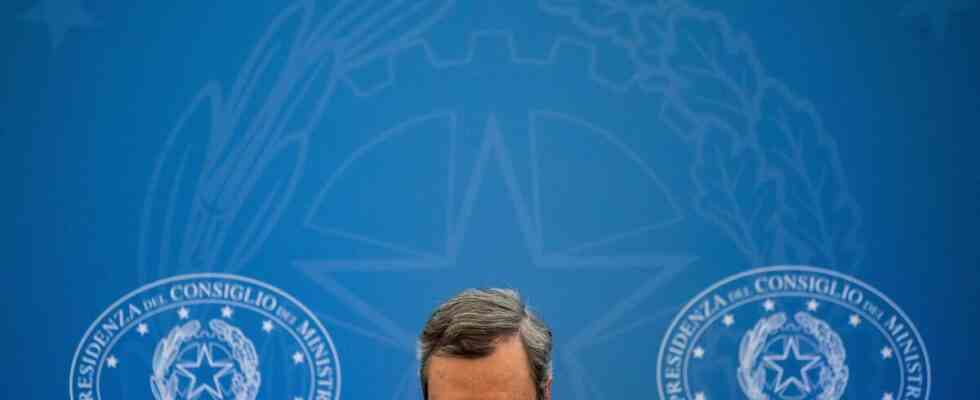

After a year and five months at the helm of the Italian executive, Mario Draghi finally came up against the political vicissitudes of a country where only Rome is eternal. The Italian Prime Minister, weakened by the defection of a party from his coalition, presented his resignation on Thursday evening, immediately refused by President Sergio Mattarella. In the process, the latter asked him to count his troops in parliament. But what happened? Will Draghi hold out doing Cavaliere alone? 20 minutes takes stock of the political crisis in Italy.

What happened this Thursday evening in Italy?

Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi submitted his resignation on Thursday evening. A resignation immediately refused by President Sergio Mattarella and which makes it possible to “send Mario Draghi back to parliament to check whether a majority still exists for this government”, explains Lorenzo Castellani, professor of political science in Rome. The head of the Italian government having to go Monday and Tuesday to Algiers, this confrontation with the elected officials is planned for next Wednesday.

Mario Draghi had announced his intention to throw in the towel after the decision of the 5 Star Movement (M5S), a member of his coalition, to boycott a vote of confidence in the Senate in the middle of the afternoon. And, in line with expectations, senators did not participate in the vote of confidence requested by the executive on a decree-law containing measures of around 23 billion euros to help families and businesses in the face of inflation. . If the text is passed, Mario Draghi considers that his government is becoming “political” and considers that he has not been mandated to lead a cabinet of this nature: “I have always said that this government would continue only if it had a clear perspective to carry out the program” on which it had been invested.

Where do the dissensions come from within the Italian government?

At the head of the Italian executive since February 2021, Mario Draghi succeeded Giuseppe Conte, leader of the 5 Star Movement, an anti-system formation created in the late 2000s and which has since largely returned to the ranks. Mario Draghi had moreover arrived in business to form a sufficiently broad and solid coalition to overcome the pandemic emergency and the ensuing economic crisis. Apart from the Fratelli d’Italia party (extreme right), the main parties represented in parliament joined the coalition, from the centre-left (Democratic Party, Italia Viva) to the League (extreme right, anti-immigration), via the party of Silvio Berlusconi Forza Italia (centre right), and the M5S.

But the frictions have not ceased with the M5S, whether within the party or within the government. And it is in particular his positioning in Draghi’s grand coalition of national unity that has given rise to internal dissension, between the supporters of Guiseppe Conte, guardians of the party’s original doctrine, and Luigi Di Maio, head of diplomacy, who plays now fully the card of the former boss of the ECB.

These political tensions, coupled with personal rivalries, worsened with the Ukrainian crisis, Conte opposing the delivery of arms to kyiv. The M5S also believes that the government is not doing enough for the most modest and the ecological transition. Di Maio ended up slamming the door and founding his own party in early July.

And what is this story of the incinerator capable of bringing down Mario Draghi?

Rome has the sinister – and deserved – reputation of being a dirty city: garbage is picked up haphazardly and hordes of wild boars take advantage of this to shop in the outlying districts. The former M5S mayor of the Italian capital, Virginia Raggi, tried to remedy this, in vain. The authorities denounce the stranglehold of mafia groups on the collection network and the chronic absenteeism of agents. Since then, a mayor from the Democratic Party has been elected. And with the government, the decision was made to build an incinerator.

However, the famous decree-law on aid for purchasing power boycotted by the M5S in the Senate provides extraordinary powers to the mayor to carry out the project. Unacceptable for the M5S, which believes that this incinerator will pollute, cost a fortune and above all that it will not solve the immediate problem, since it will take years to build it.

Is the M5S collapsing?

The M5S, winner of the last legislative elections in 2018, with 32% of the vote and a relative majority in Parliament, has since continued to plummet in voting intentions, today at 10%-11%. After his rout in the partial local elections in the spring, which revealed his weak roots in the territories, he is looking for a new lease of life. Giuseppe Conte can count on the support of the founder of the movement, the former actor Beppe Grillo, for whom the elected 5 Stars are not there to pass the dishes: “The M5S makes M5S”, he says.

“The M5S is collapsing in the polls and needs to recover visibility (…). He wants to be at the center of attention”, analyzes however Lorenzo Codogno, former chief economist of the Italian Treasury and visiting professor at the London School of Economics.

Why does Mario Draghi, who retains the majority, want to leave?

Even if the Covid-19 pandemic has exploded the strict deficit criteria defended by Brussels, Mario Draghi, a former central banker in Frankfurt, is perceived by the European Commission and the markets as a white knight of budgetary orthodoxy, a pledge rigor (or austerity according to its detractors) in a politically unstable and economically fragile country.

Only, at 74, this economist who has never sought an elective mandate does not want to be drawn into the traditional games of Italian politics. He was invested in his name, to save Italy from living “a Greek nightmare” after the pandemic which plunged the GDP of the third largest economy in the euro zone and deprived millions of workers of income. And if in the name of this vital emergency, he welcomed into his team the carp and the rabbit, from the left to the League of Matteo Salvini, it is not to play playground referees.

What is Mario Draghi’s record?

Just under 200 billion euros between 2021 and 2026: this is the manna negotiated by Mario Draghi with his European partners to keep Italy afloat. No other country has received so much. Brussels has already disbursed 45.9 billion, as the reforms required in return have been undertaken, for example that of justice, one of the slowest and most inefficient in Europe.

“But many of the most delicate and politically controversial reforms are on hold,” notes Lorenzo Codogno, Italy’s former chief treasury economist. “He should have found the lowest common denominator to do at least the reforms planned by the recovery plan and considered quite neutral. But bringing such diverse political forces together is an almost impossible mission.”