Even after five years and hundreds of days with the power suddenly gone, it’s amazing how hard it is for the brain to accept the fact that pressing light switches doesn’t get the lights to respond at all. You walk into the bathroom and put your hand on the switch, and it takes a few seconds each time to remember that there’s no electricity. If he’s back in the middle of the night, all the rooms are often brightly lit because all the switches had been flipped beforehand.

We have been living in South Africa for five years, for five years we have been struggling with power cuts, sometimes more, sometimes less, often not at all. A few weeks ago there was no electricity for about ten hours a day, during the day, right now it’s closer to two or no interruptions. While many people in Europe are wondering whether there will be enough electricity and gas in winter, people in South Africa already have some experience of what it’s like when nothing comes out of the socket. When traffic lights stop working, trains stop, restaurants have to close and the alarm systems no longer sound the alarm.

It’s been like this since 2007 because the state-owned electricity company Eskom, which is supposed to produce 95 percent of the electricity required in South Africa, has been so run down through corruption, incompetence and indifference that on bad days it only generates half of the energy that it needs country needs. South Africa can’t complain about a lack of wind and sun, but the ruling ANC has been betting on coal for decades, partly because it thought the tens of thousands of coal miners and their unions were a constituency that shouldn’t be disappointed. The coal-fired power plants are old and vulnerable, one constantly fails. Sometimes arsonists and saboteurs are at work. Millions of South Africans don’t want to pay for electricity anyway, they leave bills lying around or illegally tap into the lines. What began in townships like Soweto as a protest against the apartheid regime has now become a kind of tradition that is difficult to part with. The state-owned company has therefore accumulated a mountain of debt of 25 billion euros. There is hardly any improvement in sight. Although private suppliers are now also allowed to feed electricity into the grid from wind and solar energy, the cables for this are often missing. Nothing will change for now. On the contrary: Eskom has already announced that further dramatic failures are to be expected. Even at level eight, it doesn’t get much worse than that.

Gas cookers are often sold out

Millions of South Africans have downloaded apps to their smartphones that show them how long the power outage will be in which region in the coming days if there is not enough for everyone. It’s like looking at the weather to plan for the coming days. Can you celebrate children’s birthdays on Saturday? Or go out to eat in the evening? When are the trains departing?

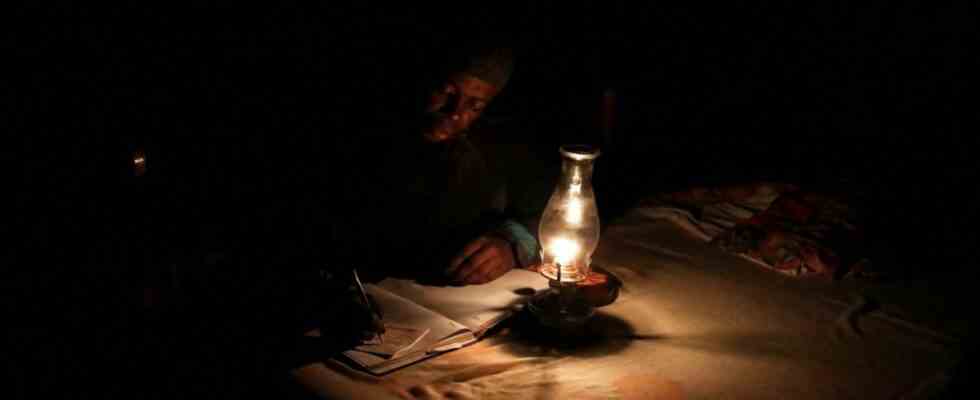

At level one it is only one to two hours, at level four it gets more uncomfortable, level six can mean almost ten hours without electricity. Sometimes it’s a little better in Cape Town because there’s another dam here that supplies a little more energy. Nevertheless, everyday life often looks like there is no electricity to make coffee in the morning and none to cook in the evening. Some find it quite romantic to sit on the balcony by candlelight. But millions don’t have a balcony and have to plan every day: when will the children do their homework, when is dinner and how is it prepared? There is a lot of grilling, gas cookers are often sold out when the failures increase again.

In winter it can be particularly unpleasant because the houses are poorly insulated and, if at all, are heated with air conditioning, which of course then fails. Some households then have no water because the pumps are on strike.

Of course, who is affected and how badly is also a question of money: Tourists usually do not notice much. Some wealthy people have bought diesel generators. At least we have a small battery that you can use to turn on a lamp and charge the phones. But many just sit in the dark. In areas where the crime rate is already high, many don’t dare go out on the streets after dark.

Ministers enjoy their free power supply

Some are happy when the whole family sits around a small fire in the yard and garden. Some are less able to cope with the situation. Livelihoods are endangered, the economy suffers. Craftsmen have to close their businesses, even some hospitals do not have a functioning emergency supply. If the electricity is gone for many hours, the cell phone batteries and power banks are empty.

“People are frustrated, some are angry, some are showing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder,” Sinqobile Aderinoye, a psychologist in Johannesburg, told local media. “The brain starts thinking we’re being attacked. The body is then told we’re in danger, and we create a fear response.” There is also a certain disillusionment: the state is letting its citizens down. The ministers of the corrupt ANC government, who are responsible for the whole mess, enjoy free, uninterrupted power supply in their state-funded residences in Pretoria. The anger is of course great, but surprisingly not so great that there would be mass demonstrations with at least a few people standing in front of President Cyril Ramaphosa’s illuminated villa. It’s a mix of deadening and a willingness to persevere: you can have a good time even in the dark. You just have to plan a bit. We recently ran out of power in the middle of cooking pasta. The attempt to boil the water on the 400-degree charcoal grill failed. Nothing worse has happened so far.