More and more schools are inviting soldiers to class. Not to promote the profession, but to talk about security policy. Can this even be clearly separated?

Shortly after 10 a.m. in Geldern, Lower Rhine. It’s a special start to the day for the students at the Lise-Meitner-Gymnasium: they have a visit from the Bundeswehr. For many in the group it is the first encounter with a soldier, but for Captain Jos Meinköhn it is a routine event.

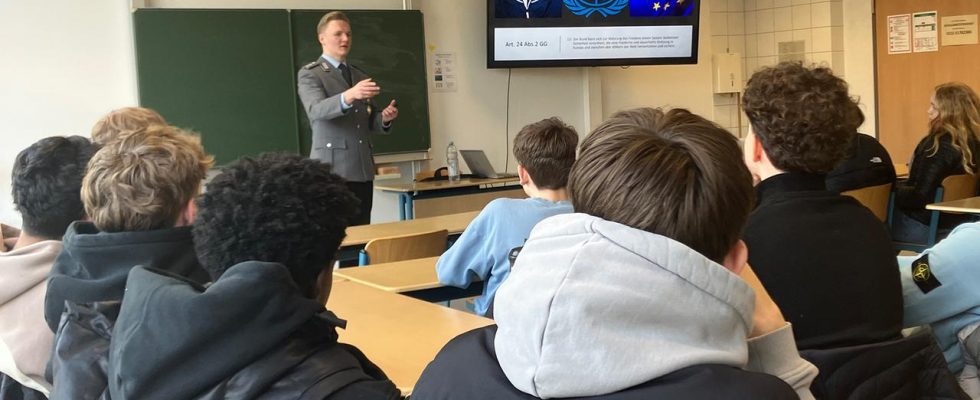

“Good morning! Is it okay if we are on first name terms?” he asks the group in a friendly manner. A nod and “Sure” comes back. Meinköhn wears a uniform with a shirt, tie and gray jacket. His blonde hair is strictly combed back. He stands straight, speaks loudly but calmly.

First, the early 30-year-old talks about his business studies in the Bundeswehr, including a semester abroad at a US military academy and a subsequent NATO deployment in Lithuania. At the beginning it wasn’t that easy to have all the weapon names and commands in English.

“Barrier tip of the Public relation”

Youth officers work for the Bundeswehr’s information service – i.e. in public relations. They are invited primarily by schools and are supposed to act as security policy speakers to provide information about the Bundeswehr’s goals and interests abroad and to talk about possible deployments at home.

In 2022 alone, youth officers gave 4,308 such lectures at schools and occasionally at universities. Before the pandemic there were around 3,350 per year.

Youth officer Jos Meinköhn speaks to the students of the Lise-Meitner-Gymnasium in Geldern.

Lectures, troop visits, excursions

Captain Meinköhn suspects that the increase has something to do with Russia’s war against Ukraine. That’s why interest in schools has increased.

Classes from level 9 onwards are attended. In addition to 90-minute lectures, the offer also includes visits to troops and overnight trips and simulation games in which young people can take on the role of a head of government, minister or an NGO. The aim is to convey security policy connections in a lively manner.

Lieutenant Colonel Ulrich Fonrobert, head of information work in the North Rhine-Westphalia state command, describes youth officers as the “spearhead of public relations.” After all, not everyone is allowed to do this job. All youth officers are well trained, most of them have studied politics or something similar and have been deployed abroad for the Bundeswehr, he emphasizes.

Education Union condemns “attempts at advertising”

Criticism of the work of youth officers comes from the Education and Science Union (GEW). The GEW is the largest education union in Germany and claims to have around 280,000 members. They work at kindergartens, schools or universities.

On its website, the GEW calls for the “Bundeswehr’s influence in schools to be pushed back.” Political education belongs in the hands of teachers and not in the hands of youth officers. In its statement, the GEW emphasizes that it “condemns any advertising attempts by schools.”

Is the work of youth officers in schools advertising? “Yes,” says Lieutenant Colonel Fonrobert. But it is no more or less advertising than a soldier in uniform walking around outside.

However, youth officers would not promote a career in firearms. That’s what career counselors are for. Cooperation agreements between the individual school ministries and the Bundeswehr prohibit advertising for activities with the Bundeswehr.

Citizens in uniform

During the lecture, a student asks questions about the entry requirements for an officer’s career. Captain Meinköhn refers to the Bundeswehr’s careers page.

A student said afterwards: “I had the feeling that I had learned something about the soldier’s profession. It was particularly exciting to find out something about his personal path. But it didn’t feel like I was here want to sell someone a job.”

For youth officer Meinköhn, presenting his career is not an advertisement for the profession. “For example, if I mention that I was in Lithuania, then specific questions can later be asked about the NATO mission there.”

Christian Brauers teaches politics and social sciences at the Lise-Meitner-Gymnasium and regularly invites soldiers. “It’s important to stay in touch with the Bundeswehr and get to know the citizen behind the uniform,” says the teacher. “There was already someone here who talked about his post-traumatic stress syndrome. If so, that would definitely not be good advertising for the profession.”

In all these years, he has only noticed once that the visit was promotional, says Brauers. “There were a bit too many beautiful Bundeswehr photos in the presentation for me.” There are divided opinions among his colleagues, but he hasn’t felt any pushback from parents so far.

Parents disagree

Parents’ attitudes towards visits by the Bundeswehr to schools vary greatly, says Claudia Koch from the Federal Parents’ Council. “Even if we think directly about career orientation.” It is at the discretion of the schools how the lessons are organized.

“We don’t want to make any regulations. That’s not our job.” It’s all about the right integration of such a visit, emphasizes Koch, and that depends on the preparation and follow-up by the teacher.

The GEW calls for peace initiatives to be given the same opportunities as the Bundeswehr in schools. Such events, just like a visit by a youth officer, must be prepared and followed up by teachers, emphasizes politics teacher Brauers. This applies to every external visit.