Antibiotic-resistant bacteria pose an ever greater challenge to medicine. German researchers are therefore increasingly referring to bacteriophages again. Bacterial herds are specifically attacked by the harmless viruses.

Some people may find it risky to rub viruses into wounds, breathe them in, swallow them or even inject them into the bloodstream. But in the so-called phage therapy, bacteria-eating viruses that are harmless to humans are actually used. With the increasing number of antibiotic resistances, this form of therapy, which has hardly been used for a long time, is receiving more attention again. But is it the solution to the great crisis in medicine? Two German projects are about to treat patients.

Bacteriophages are constantly around and inside us. An adult human consists of about 30 trillion body cells, 40 trillion bacteria – and 300 trillion phages, says phage therapy expert Christian Willy, director of the clinic for trauma surgery at the Bundeswehr Hospital Berlin. Bacteriophages are viruses that start multiplication programs in bacteria until the mass of newly produced viruses causes the bacterial cell to burst. Bacterial accumulations, for example in a focus of inflammation, can thus disappear quickly.

Phage therapy as a response to antibiotic resistance

One of the projects in which patients will soon be treated is “Phage4Cure”, in which a therapy with inhalable phages against the dreaded hospital germ Pseudomonas aeruginosa is developed. The pathogen often colonizes the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. A clinical phase I study on basic tolerability is to start in late summer, as Christine Rohde at the Leibniz Institute DSMZ (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH) in Braunschweig says. Contrary to what is usually the case, there is also a direct cohort with patients. “If phase I is successful and the patients feel better, then a real milestone for phage therapy in Germany will have been reached.”

A few patients are already being treated in Germany for whom the available approved therapies are ineffective. For example, from Christian Kühn, head of the National Phage Center at Hannover Medical School. “I see every day what antibiotic resistance does,” emphasizes the doctor. “We need alternatives.” More than 30 patients have already been treated in Hanover, often against Staphylococcus aureusa bacterium that can cause stubborn wound infections.

The second major German project, the “PhagoFlow” project carried out by the Trauma Surgery Clinic at the Bundeswehr Hospital in Berlin, also relies on the individual production used for each individual patient – known as magistral application. While “Phage4Cure” is about a clinical picture, a pathogen and an administered mixture, “PhagoFlow” is intended to treat different clinical pictures caused by different pathogens, as project manager Willy explains. From the second half of the year, the first patients could be treated, he hopes.

Antibiotics and bacteriophages: what are the differences?

Bacteriophages have been used to fight infections for about a century. They were discovered a good ten years before the Scottish bacterium researcher Alexander Fleming discovered the antibiotic effects of penicillin in 1928.

A big difference between the two bacteria killers: While antibiotics work more like a weapon of mass destruction, phages are contract killers with a very specific goal. They attack only one type of bacteria at a time, very often only one specific strain of a type. This makes their use complicated: First, the appropriate phage has to be found for the respective bacterial strain of a patient. “And more than one strain usually plays a role in a critical infection,” explains Holger Ziehr, Head of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology at the Fraunhofer Institute for Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (ITEM).

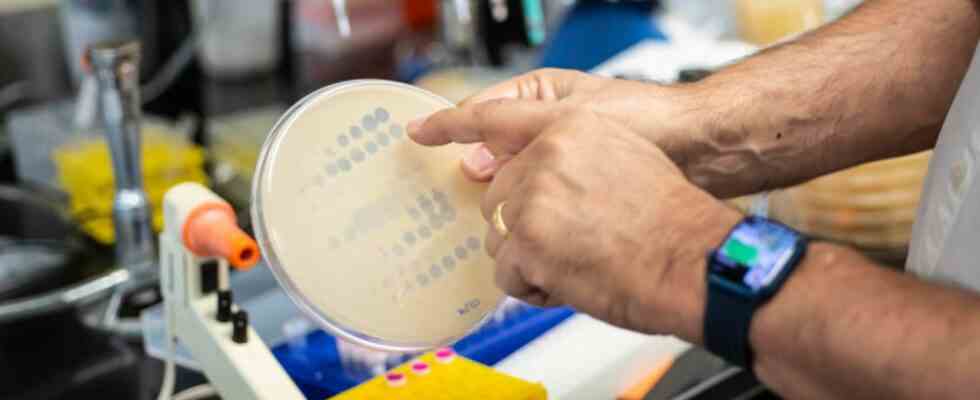

But where can you find suitable phages to combat a specific pathogen? Experts often choose a very simple source for this: “waste water,” says phage researcher Alexander Harms from the Biozentrum at the University of Basel. First, the bacteria against which phages are to be used are cultivated on nutrient plates. The water sample comes on the bacterial lawn. If a bacterium-killing phage is present, a hole is created in the bacterial lawn – the virus is isolated from this spot and multiplied in the laboratory.

So much more effort than pulling a pill that works against many pathogens out of the drawer. But the wonder weapon antibiotics is in danger of becoming dull. It is estimated that more than 30,000 deaths in the EU are caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria every year. According to estimates, there are around 700,000 worldwide. Ascending trend. Can phage therapy help?

USA and Europe want to revive phage therapy

In the Eastern Bloc countries – where there was initially no broad access to antibiotics – phages continued to be used frequently. To this day, institutions from such countries are world leaders, most notably the Georgi Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia. Other countries such as the USA, Belgium and France are now reviving this form of therapy. Examples from the USA show that it is now possible to create a suitable phage therapy for a patient within 10 days, says Christian Kühn from the phage center in Hanover.

Convincing results on the efficiency of phages in very large clinical studies, as they have become the required standard in drug research, are not yet available for the phages that can often only be used individually, as phage expert Christine Rohde says. Individual case reports and smaller studies show impressive success, as the German experts explain.

In a recently presented study, 20 patients with intractable bacterial infections were treated with bacteriophages. The therapy was successful in eleven patients, the researchers reported in the journal “Clinical Infectious Diseases”. Accordingly, there were no side effects. Ziehr refers to the heterogeneous group of participants, which included children as well as adults with various clinical pictures, complex infections and different types of pathogens. The fact that, given these circumstances, more than half of the participants responded to the therapy is impressive, says the expert, who was not involved in the work.

Bacteriophages will not completely replace antibiotics, as the experts emphasize. A promising way could be the combination of bacteriophages and antibiotics, based on the so-called phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS), explains the Berlin phage researcher Willy. It has been shown that resistant bacteria can become sensitive to antibiotics again in a patient who has previously been treated with phages.