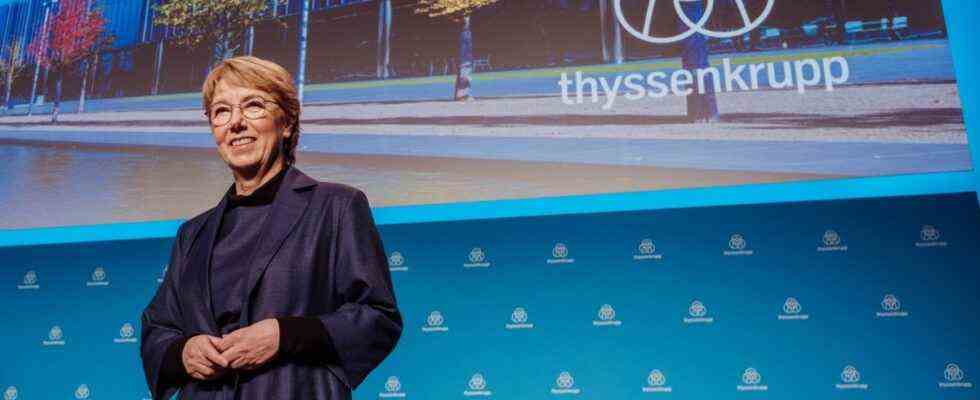

Martina Merz is not comfortable with early fame. As the business journal manager magazine The Thyssenkrupp boss recently voted the most important woman in the German economy, Merz was skeptical. She would rather continue to rebuild instead of being celebrated. And she doesn’t see herself as a role model for female careers – unmarried, without children: “My biography leaves the impression that women can only achieve something with a full focus on their careers,” says the 58-year-old. In her generation, the few female managers often had no family, and given this one-sidedness, that is not a model for the future.

Despite all the understatement, Merz is still striking a very solemn tone in the digital general meeting this Friday: “We have left the relegation zone,” says her speech, which Thyssenkrupp published in advance so that shareholders can address it in their written questions. “We want and we will play at the top again,” says Merz.

In fact, it is an unusual turn of events how that woman from Swabia led this male-dominated Ruhr group out of its existential crisis. At least up to here.

After studying mechanical engineering, Merz worked for Bosch for more than 20 years and was once the very first woman to manage a plant for the large automotive supplier. 2015 should be a quieter time, as a member of the supervisory board at Lufthansa and Thyssenkrupp; there Merz became chief inspector. But the calm was over in 2019.

Merz analyzed the situation harshly

At that time, Thyssenkrupp had a profitable elevator division, but other businesses such as plant construction accumulated losses. Billions in debt weighed on Germany’s largest steel company after it gambled with steelworks in America years ago. In addition, there were high pension obligations. The bottom line was losses – and too little money for investments.

In this situation, two and a half years ago, Merz practically sent himself from the supervisory board to the top of the board – a rare occurrence – and replaced Guido Kerkhoff. Since then she has been sitting in the wood-panelled executive office of that proud headquarters made of glass and steel in Essen. “I’m sitting here on furniture, I can’t even put my feet on the floor,” she said in an interview.

Thyssenkrupp’s glass headquarters in Essen: an expression of the self-confidence of years past.

(Photo: Marcel Kusch/dpa)

It took Merz almost four months to make a decision that no one had brought to heart before: She sold the elevator business, her pride, for a good 17 billion euros. This was the only way Thyssenkrupp could “get going again,” Merz argued, it was the result of their sober analysis.

After the sale, Thyssenkrupp was able to pay off debts and invest more again: in new coatings for car panels, for example, or in the construction of ever larger roller bearings for wind turbines. And the group coped with depreciation and losses during the Corona crisis without running out of money.

Driving in multiple lanes, reducing costs: Merz’s demanding nature can also be an impertinence

It is notorious internally that Merz is keeping alternatives open for as long as possible: Should it be said in the meantime that Thyssenkrupp could also list the elevator division on the stock exchange, the competitor Kone should say how much one would like to merge. “If you want it to be great, I recommend multi-lane,” Merz once said via Twitter.

According to Thyssenkrupp, it is expected to carry out the largest conversion of all time. She turned every stone – and subsequently also sealed the sale of loss-making daughters: for example, the business with mining machines or a stainless steel plant. In total, up to 12,000 jobs will be lost at Thyssenkrupp over the years.

If a division is not one of the top three in its branch, then it is in a difficult position. Merz has not yet sold all the subsidiaries for which Thyssenkrupp is not the best owner in its opinion; the future of cement plant construction, for example, is still open. “Time is running out for a solution here,” warns Ingo Speich from Deka, the fund house of the savings banks.

Also because severance payments initially make any job cuts expensive, Thyssenkrupp reports a loss of 25 million euros for the past fiscal year – which is still manageable for a billion-dollar company. Once again, shareholders cannot be paid a dividend, says Merz. “But we’re working hard on it.” After all, those businesses that Merz wants to hold on to report significantly higher profits than before the boss took office. However, the respective competitors are still more profitable, as investors have been criticizing for years.

The fund house Deka demands that Thyssenkrupp should sell the arms business

Thyssenkrupp has a good part of the conversion behind it, “we can still do the rest,” says the group boss. Of course, this rest also includes the complex plan to outsource the steel works with around 26,000 employees on the Rhine and Ruhr to an independent company. The steel business is more volatile than the other sectors, says Merz.

Blast furnace in Duisburg: Steelmaking is Thyssenkrupp’s core business. But the group has long been making more money with car parts or the materials trade.

(Photo: oh)

Meanwhile, higher prices for CO₂ emission rights and coal are on the agenda, warns Deka representative Speich, “and threaten the existence of the steel business.” The restructuring does not go far enough for the experienced speaker at the annual general meeting: In his opinion, Thyssenkrupp should also sell the armaments business with naval ships, since the profits are disproportionate to the image risk. The group itself is examining whether the marine division could merge with competitors; after that, Thyssenkrupp would no longer necessarily have to hold the majority.

Ultimately, criticizes Speich, Thyssenkrupp burned money in the past fiscal year. “It remains to be seen whether the entire group will stabilize.”

After Martina Merz’s time at the top of ThyssenKrupp began like a firefighting operation – initially a congress hotel served as her residence – one is now wondering whether Merz could not extend her three-year contract until March 2023. So far she hasn’t said anything about it, just that she doesn’t want to be boss somewhere else. At some point the quieter time should really begin.