Status: 09/26/2022 4:40 p.m

Italy is the third largest country in the euro zone. Investors on the financial markets are now wondering how the state, which is already highly indebted, is supposed to finance the legal alliance’s expensive plans.

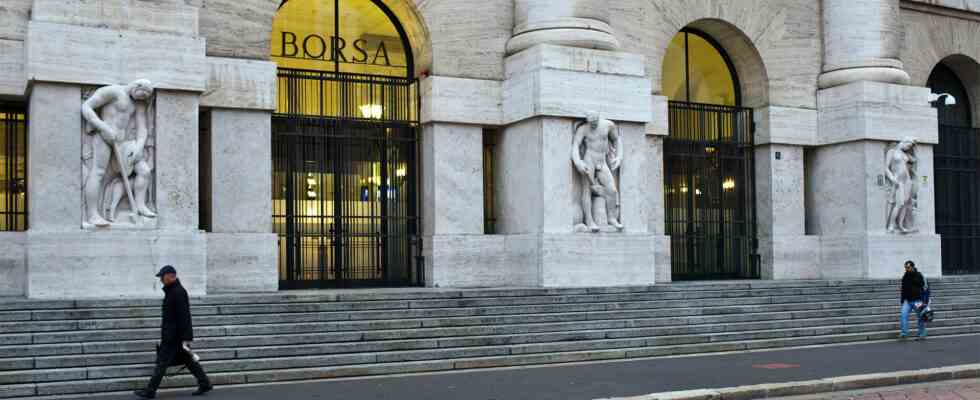

While right-wing parties across Europe celebrate the victory of the right-wing alliance in Italy, investors on the stock exchanges are skeptical about the outcome of the election. The euro, an indicator of the economic situation in the European Union, is under severe pressure. At times, the common currency fell to a 20-year low.

The decisive factor will now be the direction taken by the new Italian government, said economist Marco Wagner from Commerzbank. He doesn’t expect anything comparable to the structural reforms initiated by Prime Minister Mario Draghi: “Quite the opposite. I could even imagine that one or the other that Draghi has already initiated might be rolled back.”

This includes, for example, topics such as a later retirement age or a far-reaching tax reform. The problem: Italy already has an immense mountain of debt. The projects of the legal alliance cost a lot of money. In view of the rising interest rates, however, it is becoming increasingly expensive for Italy to take on new debt.

The state’s room for maneuver is limited

What’s more, the new government can’t do as it pleases. Italy is part of the European Union, is the third largest economy in the euro zone and is also financially dependent. Around 200 billion euros alone will flow to Rome from the EU’s Corona reconstruction fund. “As soon as this money has flowed from Brussels, I can well imagine that the conflict with Brussels will increase,” fears Edgar Walk, chief economist at Bankhaus Metzler. That will also affect the financial markets: “You will see it best in the development of Italian government bonds,” said Walk.

The day after the election, 10-year government bond yields shot to their highest level in nine years. The market is nervous, says bond expert Arthur Brunner from the ICF Bank: “Italy currently has to pay more than 4.4 percent interest in the ten-year range. And I believe that these interest rates alone will be forced on the spending policy better be more careful.” Brunner is certain that Europe is facing difficult times. Georgia Meloni, soon to be Italy’s new prime minister, is still not showing her cards.

Growing mountain of debt due to the pandemic

In its election program, the right-wing conservative bloc promised lower taxes for families, the self-employed and companies. So there should be a “flat tax”, i.e. a uniform tax rate of 15 percent on annual income of up to 100,000 euros. That would cost the state a good 50 billion euros a year. In addition, VAT on energy and other important goods is to be reduced. According to experts, this would burden the national budget with 30 billion euros.

Italy’s debt is more than 150 percent of economic output. In 2018 it was 132 percent. The corona pandemic has made the mountain of debt even greater. “Across the Italian political class, debt is simply not discussed anymore,” says Tim Gwynn Jones, an analyst at the consulting firm Medley Advisors.

Total interest costs increase only slowly

Experts like Roberto Perotti, economics professor at Milan’s Bocconi University, assume that the legal alliance’s election promises would cost the state a total of more than 100 billion euros. He is certain that there will be a debt crisis, even if the government only pushes through those plans “that relate to taxes and pensions.”

Other experts are less concerned – pointing out that the average cost of interest on Italy’s debt will be slow to rise even if government bond yields continue to rise. Because new bonds initially only make up a small part of the total bond volume.