The fact that Franz Kafka not only wrote, but also drew, became apparent to a broad audience at the latest when S. Fischer Verlag put Kafka drawings on the front pages of the paperback editions “The Judgment” (1952), “Amerika” (1956) and ” The Trial “(1960) continued. A figure, covered in black, was surrounded by a grating, legs spread, and seemed to await the verdict with arms folded behind his back.

Was the empty rectangle suspended vertically between two beams, in front of which another black figure, seeking support, touched one beam with its right arm, a mirror? The tips of the toes of the uncomfortable third black figure, who was sitting on a chair with a slightly bent back, hardly touched the floor below the table on which the head lay between lozenge-shaped, grotesquely folded arms. That had to be the defendant, depressed by the force of the trial.

Max Brod made the drawings available. He had previously published Kafka’s drawings in his Kafka biography of 1937 and in other books, for example in “Franz Kafka’s Faith and Teaching” (1948). There he affirmed in a follow-up comment “On the illustrations” his view that Kafka was “an artist of special strength and character, even as a draftsman” and added: “Up until now nobody has considered it necessary to deal with Kafka’s dual talent, the parallels to pursue between drawing and narrative vision. “

Franz Kafka: The drawings. Edited by Andreas Kilcher. With the collaboration of Pavel Schmidt. With essays by Judith Butler and Andreas Kilcher. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2021. 368 pages, 45 euros.

Brod reported at the same time that Kafka was “even more indifferent, or rather, more hostile” to his drawings than his literary works. He had the “graffiti” given to him, took some things out of the wastebasket, cut others off from the edges of the college books on which it was written during the joint law studies: “What I did not save has perished.”

About forty Kafka drawings were known so far. Now, edited by Andreas Kilcher, Professor of Literature and Cultural Studies at the ETH Zurich, an opulent volume has been published that has 163 entries in his “Catalog of Works”. The prerequisite for this considerable increase is the end of a legal dispute, which Kilcher briefly summarizes in his tradition of the drawings.

Max Brod had bequeathed his own estate as well as the manuscripts and letters in his possession to his longtime secretary Ilse Ester Hoffe as a gift. After Hoffe’s death in 2007, the Israeli National Library – whose predecessor had shown little interest in Kafka manuscripts decades earlier – claimed the entire Brod estate, including the partial Kafka estate contained therein, with reference to a paragraph in Brod’s will.

Max Brod cut out these drawings from a notebook by the young Kafka

Against the reference by Hoffe’s daughters and heiresses to the donation, which was documented twice in writing, the Israeli courts upheld the National Library’s claim right up to the final decision of the Supreme Court in August 2016. Since Kafka’s manuscripts and letters were in a bank safe in Zurich, the decision made in Israel had to be legally confirmed in Switzerland. That happened in April 2019.

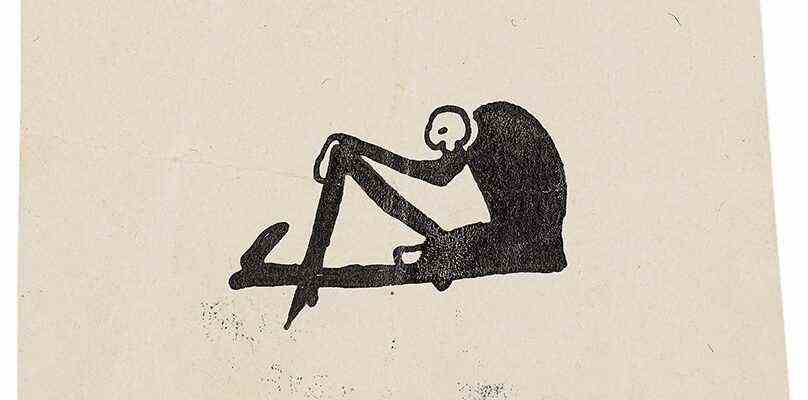

What was in the manuscripts and letters transferred from Zurich to Jerusalem has long since entered the Kafka editions. Most of the drawings that had come down to us on single sheets, paper clippings, printed or handwritten notes and smaller bundles of drawings were unknown. The booklet of drawings by the young Kafka, made between 1901 and 1907, plays a key role, from which Max Brod cut out the black inked figures that had a lasting impact on the image of the draftsman Kafka through the Fischer paperback editions and their frequent reproduction.

The six figures that Brod published are now being stepped aside by four previously unknown ones, also equipped with dot-dot-comma-line faces, some with heads that float in the vacuum above their torso, one without buttocks at a table, Another seems to be seated busy draping the right leg over the straight left leg to form an isosceles triangle as much as possible. There is also a very peculiar figure of thought on a chair, head in hand, who emigrated in an unknown manner from the drawing booklet that Brod had cut up, arrives at an unknown location and has so far only been published once in a treatise on Kafka’s Jewish identity written in Hebrew has been.

The law students Brod and Kafka were also gallery visitors: drawing from the estate.

(Photo: Ardon Bar Hama / Drawings by Franz Kafka / The Literary Estate of Max Brod / National Library of Israel, Jerusalem)

It is very much to be welcomed that Andreas Kilcher has added a detailed essay “Drawing and Writing with Kafka” to the history and documentation of the drawings. Because in it he drives a cliché into the parade that fixes Jewish authors on the script and attests that Judaism as a whole is foreign to the visual arts. In this sense, Gustav Janouch had his heroes say in his “Conversations with Kafka” (1951): “We Jews are not really painters. We cannot represent things statically. We always see them in flux, in movement, as change. “

Kilcher does not stop at emphasizing the very questionable source value of Janouch’s book. It shows how strong Kafka’s interest in the visual arts was already in high school, but especially in the years of study at Prague University, when the majority of his drawings were made. The law students Brod and Kafka were at the same time gallery visitors, attended art and literary studies lectures and exercises, read art magazines and monographs on art, practiced drawing, and counted artists and budding art historians among their circle of friends.

During her student days, Martin Buber published the volume “Jüdische Künstler” (1904) with essays on Max Liebermann, Lesser Ury, Josef Israels, EM Lilien, Solomon J. Solomon and Jehudo Epstein. In the foreword he made the opening and conquering of the realm of the fine arts the distinguishing feature between “ancient” Judaism and the new, modern, current one, in which “the Jew develops into a full human being”.

During his academic years, the Prague painter Emil Orlik was influential as a representative of contemporary Japonism

Looking at the annual reports of the “Reading and Speech Hall” at Prague University, his fellow students and current gallery operations in Prague, such as the group “The Eight”, Kilcher shows the infrastructure in which Brod and Kafka’s interest in drawing was embedded into the generation-typical interest of young Jews in modern visual arts.

For Brod as for Kafka, the Prague painter and graphic artist Emil Orlik played a prominent role as a representative of contemporary Japonism and thus the reflection on the line in drawing. Orlik gave lectures in Prague on his trip to Japan in 1900/01, published features on woodblock prints in Japan, and his Japanese portfolio was exhibited in 1902 in Prague’s Rudolfinum. Kafka sent a postcard with a spring landscape by Hiroshige Montanaga to Max Brod in November 1908.

His own experiments with the line that he undertook during these years contributed to the upgrading of the sketch as an independent form in current art criticism. The fencers, in which the Borghesian fencer of the Louvre found a small-format, two-dimensional, comparatively abstract counterpart, the dancers who emerged from the view of a Japanese variety group, the horses and riders in their independent movement curves are neither dated, signed nor given titles . It makes sense when Kilcher sees in them, for example in the angry drinker who looks down at his wine glass with bared teeth, the fruits of an independent graphic impulse alongside writing.

Like an evagination of the graphic dimension of manuscripts: a drawing from the anthology.

(Photo: Ardon Bar Hama / Drawings by Franz Kafka / The Literary Estate of Max Brod / National Library of Israel, Jerusalem)

But already in those early and especially in the later years from 1909/10 onwards, in which the majority of the literary work was created, the drawings keep moving ever closer to writing. Often they do not find their place on single sheets of paper like the heads of the mother or the self-portraits, which are reminiscent of exercises in drawing lessons, but on the supports of a letter, a manuscript, a diary note. In this border area between writing and – very often – undemanding drawing, striving for completeness is treacherous.

From the letter to Milena Jesenská of October 1920, the sketch of a torture device described in the text stands out suggestively, which Kafka describes in the text: “If the man is so attached, the bars are slowly pushed out until the man tears in the middle The inventor leans a column and pretends to be very tall with his arms and legs crossed, as if the whole thing were an original invention, while he only copied it from the butcher who stretches the gutted pig in front of his shop. “

But as plausible as it is to publish the drawing booklet from the early years in its entirety or to collect all the drawings from the travel diaries 1911/12, including the (well-known) of Goethe’s garden house in the Park an der Ilm in Weimar, so much from the diaries and notebooks of the A late woman’s head from 1924, from the time with Dora Diamant, stands out, so much the heading “Manuscripts with patterns and ornaments” has to stretch the term drawing to the point of fraying, in order to use it for the strikethroughs, hatching or pictorial characters documented here to be able to bring. Rather, one could speak of a kind of protuberance of the graphic dimension of manuscripts, which is omnipresent in the archives of modern literature.

It is advisable not to freeze in the face of the drawings in front of Kafka’s complete oeuvre

Max Brod was already considering publishing all of Kafka’s drawings; the art historian Paul Josef Hodin, who came from Prague, even encouraged him around 1951 to exhibit Kafka’s drawings in major art metropolises around the world. Although Brod sold a few drawings to the Albertina in Vienna and thus brought Kafka into a large graphic collection, he soon abandoned the grand plans. They are taken up in this volume, which goes back not only to the Jerusalem holdings but also to the partial estates in Marbach and Oxford.

In her concluding essay, Judith Butler discusses the tension and interplay between writing and drawing in Kafka and finds something in common in the “impossibility of touching the ground” that runs through both spheres. Considerations about the sketch, the fragment and the incidentally improvised could be linked to the image thus called up. It is advisable not to freeze in awe of the “complete works” of the draftsman Kafka when passing through this volume, but rather not to overlook the casualness that is contained in them when looking at the drawings.