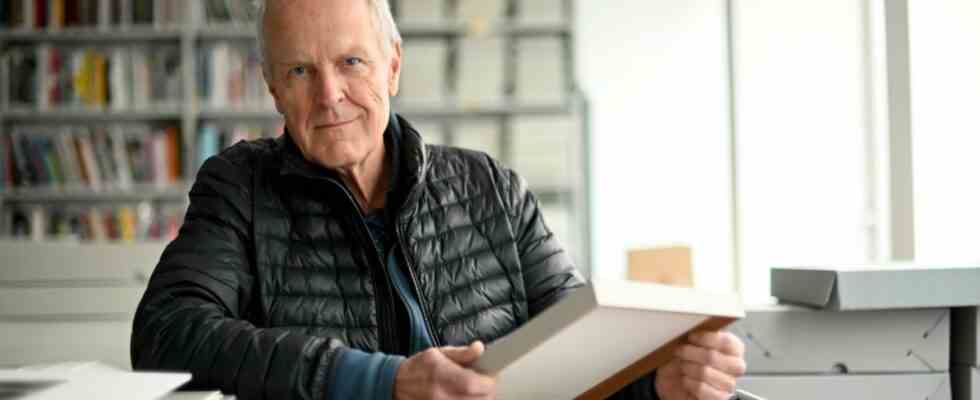

Thomas Hoepker himself would probably have recognized the iconographic status of his photograph “View from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, on Manhattan, September 11, 2001” at some point. After all, the now 86-year-old German Magnum photographer, who was even president of the photo agency from 2003 to 2007, has an extremely well-trained eye for that one special moment that makes a photograph stand out from the flood of images and turn it into an eye-catcher. And yet it was Ulrich Pohlmann, curator and former head of photography collections at the Munich City Museum, to whom he owed the insight.

Thomas Hoepker’s photograph “View of Manhattan from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, September 11, 2001” became an iconic reminder of the 9/11 catastrophe.

(Photo: Thomas Hoepker/Munich City Museum)

Because when Pohlmann looked at the various photos of 9/11 in preparation for a retrospective by Hoepker in the Munich City Museum in 2005, this previously unpublished photograph caught his attention. “I was fascinated by their casualness and the banality of the situation,” says Pohlmann. And indeed, it is precisely the everydayness of the scenery in the foreground that intensifies the horror of the terrorist attack on the towers of the World Trade Center in the background. Only after the photo was in the Munich exhibition did Hoepker publish it, which led to a report in the New York Times led and made it known worldwide.

Much is washed up on the shores of the museum like flotsam or flotsam

The fact that this photo belongs to the photo collection of the Munich City Museum – a gift from Hoepker – has to do with Pohlmann’s personal relationships with photographers or their families and estate administrators, as with many others. A lot of things are “washed up on the shores of the museum like flotsam or flotsam,” he says. He had just been offered something from a family estate: the large photo archive of the Munich landscape painter, Friedrich Voltz.

But a lot is only thanks to many years of intensive negotiations. Pohlmann, who has now retired after more than three decades as head of the collection, can tell a few stories about this. Targeted purchases include, for example, photographs of the transport of the Bavaria by photo pioneer Alois Locher from the mid-19th century. “For a long time, they were considered the first photo reports,” says Pohlmann, “the city stood guard when the parts were brought from the foundry to the Theresienwiese.” But the pictures were posed. “Photo reports were not technically possible at the time because of the long exposure times.”

Pohlmann was able to purchase the Dietmar Siegert collection in 2014. It includes Joseph Albert’s photograph of participants from the Jung-Munich artists’ society at a fairytale ball in 1862. An unknown person and the sculptor Hermann Oehlmann depict the race between the hedgehog and the hare.

(Photo: Joseph Albert/City Museum/Julia Krüger)

Initially, the focus of the collection was on Munich photography. With the acquisition of Josef Breitenbach’s estate, the collection became more international and many of the photographs depicted emigrant stories. It was the same with the estate of Hermann Landshoff, who had done early fashion photography and was Richard Avedon’s teacher. At a book launch, Pohlmann met the publisher Andreas Landshoff from Hermann Landshoff’s family.

Hermann Landshoff: The Surrealists (back row: Jimmy Ernst, Peggy Guggenheim, John Ferren, Marcel Duchamp, Piet Mondrian; middle row: Max Ernst, Amédée Ozenfant, André Breton, Fernand Léger, Berenice Abbott; front row: Stanley William Hayter, Leonora Carrington, Frederick Kiesler, Kurt Seligmann. In the Townhouse of Peggy Guggenheim), New York, 1942.

(Photo: Hermann Landshoff/Munich City Museum)

His portrait shots are a “Who’s Who” of that time. 3600 originals and one-offs. It took 20 years for everything to be clarified – sometimes even before US courts. “A wonderful example of the history of photography and emigration,” enthuses Pohlmann.

Much of what was on the collection director’s wish list could not be purchased with one’s own funds. The purchase budget for the photography collection is just 10,000 euros per year. “Building trust that the photos don’t disappear into the depot, but are shown and loaned out in the right context, is extremely important,” says Pohlmann. This was the only way he could negotiate good terms or managed to get a collection like Ann Mandelbaum’s recently donated to the City Museum. But cultural foundations have also made numerous purchases possible, because in some cases millions of euros had to be raised.

“We have to find the thread of Ariadne to convey what is happening and how to deal with it critically.”

Recently, the question of how to deal with digital archives has often been raised. “The format of a photograph is still important, but the question of format has become more fluid in the digital age.” And the flood of images is not a new phenomenon, but has reached a new quality through digitization. Furthermore, exhibitions no longer only take place in museums and galleries, but also in digital space. Museums have to react to this. “The Fotomuseum Winterthur is the first museum to have a digital curator, and the Museum Folkwang is probably also thinking about it,” says Pohlmann. You are looking for ways to not only show the works, but also what is happening around them in the digital world.

In recent years, conservation awareness has developed significantly. The city museum now has two female photo restorers. And in the still relatively new depot in Freimann, the possibilities for storing photographic archives and legacies, ranging from glass plates to digital recordings, are very good. Pohlmann knows: “That’s not the case in many museums. Great efforts have to be made in terms of conservation,” he demands.

He is also concerned with how contemporary tastes and technical possibilities are changing. “Does the future consist of an atomized pictorial reality? What is iconic in the pictorial universe?” This is accompanied by questions about the construction of memory – as in the case of the Hoepker photo – and identity.

Curating always means deciding what is important and what will become important. “One is like a membrane, like a filter.” So where will the media go? “Virtual space is becoming ever larger and more important, but at the same time the need for materiality is also increasing. We have to ask ourselves: What can museums do in this regard?” Also with regard to new technical possibilities such as apps that change images. “We have to find the thread of Ariadne to convey what is happening and how to deal with it critically.”

“There are huge deficits in university teaching.”

He is also concerned about the academic sector. There are too few chairs, Germany lags far behind the USA and France. “There are huge deficits in university teaching, something has to happen.” Photography as an art form has long since found its place in art history. The German Photo Institute is also an expression of this. But the fact that the location debate, after years of dispute, was recently decided in favor of Düsseldorf instead of Essen – a political decision against the advice of the experts – appalled him.

Because cultural advisor Anton Biebl asked him, he stayed in office a few months longer than planned. “But now it’s time for the generation of digital natives to get involved,” he says, “if only in view of all the challenges that digitization of photography brings with it.” The publisher Lothar Schirmer has a big one Festschrift on the farewell of Ulrich Pohlmann suggested, which pays tribute to him and which should appear at the end of the month.

Born in Schleswig-Hostein in 1956, Pohlmann received his doctorate in the 1980s and began his professional career (with an exhibition about Wilhelm von Gloeden). He was a photo curator at the FC Gundlach Foundation and at the Cologne City Archives (which collapsed in 2009). Even today, he still remembers well how he applied for the position in 1990 on the Munich City Council and before the Mayor at the time, Georg Kronawitter. “The replacement of a collection manager in a city museum was still pretty high,” he says with a smile. There were around 70 applications, and a handful of people were invited to introduce themselves personally. “Each of us had eight minutes. Christian Ude, then Deputy Mayor, pressed the stopwatch.”

Quitting now feels “a bit unreal”. “After 32 years, I’ve grown very attached to the museum.” But the initial melancholy has given way to cheerfulness and serenity: “I’m looking forward to what’s to come.” Ulrich Pohlmann will be in Paris quite often this year, preparing a major retrospective of Henri Cartier-Bresson at the Fondation of the same name for 2024. A number of book projects are also planned.

However, his successor – the personnel details are said to be decided soon – will first be busy with the move to the Arri site due to the upcoming general renovation of the city museum. After that, the arsenal will serve as a kind of platform, and numerous collaborations with other Munich and national institutions are planned in order to remain visible. Pohlmann can well imagine sending parts of the photographic collection on trips. But that is something that others will now decide.