How strongly people are shaped by the attitudes of their time is aptly expressed in the old portrait photographs. The flyer used by the Traunstein City Archives to advertise its current exhibition shows a picture of a bride and groom from 1877. The young lady is crouching on an upholstered armchair, her husband is standing at attention next to her, both of them look quite seriously into the distance.

The couple next to it, which were photographed in 1922, form a striking contrast. It stands relaxed and smiling happily on a flower-lined terrace. What a difference in attitude. The two photographs encompass a time of extreme changes, the consequences of which are still reverberating today.

In the current state exhibition in Regensburg, the upheavals at the transition from the 19th to the 20th century are thematized using the example of the last monarchs. In the show in Traunstein, the epochal change at that time is broken down to a bourgeois small town, but the result applies to many places in Bavaria. “We want to show what consequences all of this had for the common people. And how the subjects became citizens who were suddenly able to experience achievements such as women’s suffrage,” says city archivist Franz Haselbeck, who organized the exhibition together with Judith Bader (Städtische Galerie Traunstein) has worked out.

The time span spans from Ludwig II to the Weimar Republic. The development is not presented chronologically, but in thematic blocks, whereby the outcome of every story is the great fire of April 1851, which destroyed the old town. “Traunstein, the beautiful Traunstein is in ashes!” Reported the Münchner Volksbote. It was a catastrophe that continued into the early 20th century.

The fall of the monarchy and the revolution in Bavaria are mostly traced on the basis of the events in Munich. Traunstein shows what traces the upheaval left on the countryside. The exhibition finds convincing answers to the question of why everything wasn’t sunk into chaos. Mayor Georg Vonficht proved to be a stabilizer in Traunstein. As early as November 8, 1918, when the revolution flared up in Munich, he made an appeal to the residents: “Major political upheavals are currently taking place in the capital of Bavaria. Whatever happens, this is the name for us in Traunstein the order of the day: unity, calm and order. ” In cities like Traunstein, priority was given to the continuation of the food supply and the avoidance of violence, which was supposed to get out of hand in revolutionary Munich.

Workers’, peasants’ and soldiers’ councils were formed here too, and on February 24, 1919, the red flag of the revolution fluttered at the town hall. In contrast to the state, however, in many municipalities the holders of political power were not replaced. Vonficht involved the revolutionary organs in his work. Until the revolution died out and the resident militia arrested the soldiers’ councils on May 2, 1919. The conservative forces had held their own.

The fact that Traunstein was not left behind was also due to the railway line from Munich to Salzburg

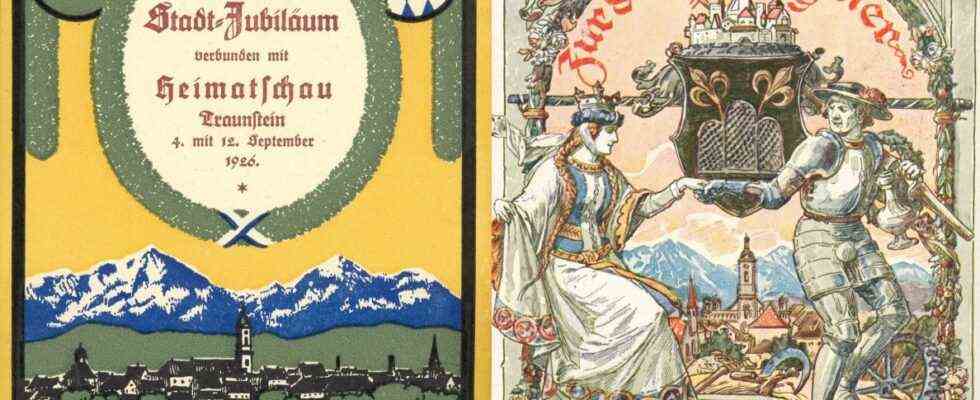

The “golden 20s” in Traunstein by no means reached the pulsating convulsions of the capital Berlin, but in 1926 they celebrated a huge anniversary celebration for the 800th anniversary of the city. Even if the date was on clayey feet, as Haselbeck says. After bad years, it became the biggest festival the city has ever known.

The fact that Traunstein was not left behind at the time was not least due to the railway line from Munich to Salzburg that was opened in 1860. The station anchored the old trading town on the map of the German Empire established in 1871. But norms, values and life models were also constantly changing in the small towns. In 1900 there were 6845 inhabitants in Traunstein. Among them were 324 Protestants and 10 “Israelites” who were looking for their place in the growing Catholic dominance. There were still hundreds of horses, cattle and pigs. The dwindling numbers, however, show that agriculture was already declining at that time.

Much of what defines the city today is rooted in this era: the development of schools, trade and business organizations and the supply of electricity, gas and water. At the same time, there was a flourishing cultural and club life. In 1891, for example, the St. George Association was founded, which revived an old horse pilgrimage to Ettendorfer Church. The Traunsteiner Georgiritt was included in the federal register of the intangible cultural heritage of Unesco in 2017.

Social tensions were a constant part of everyday life. The systematic envy of the success of Jewish entrepreneurs soon led to anti-Semitic pamphlets and acts of violence. It cannot be denied that many artisans, small farmers and servants who moved to the city full of hope ended up in the poverty of the proletariat. It is precisely here that the helplessness of politics is a phenomenon that does not depend on time. The Prince Regent Luitpold won the hearts of his subjects with his affability, but he did not solve their problems. With its passivity and unworldliness, the monarchy ultimately had nothing to counter its downfall.

“Subjects! Citizens!” Life in Traunstein between monarchy and democracy as reflected in art and culture. Municipal Gallery Traunstein, Ludwigstr. 12 to 26 September, Wednesday to Friday 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday, Sunday and public holidays 1 p.m. – 6 p.m. Tel. 0861/164319.