A few years ago the writer Christine Angot was sitting in a café near the Pompidou Center. Angot is a media star in France with a passion for the big verbal slap in the face of politicians. Nevertheless, it was to be a conversation about writing, and before the first question could be answered, Madame Angot said with a stern look at the teacher: “L’écrivain est archiseul.” It sounded like a kind of law that no one has to shake: “The writer is lonely.”

The pride in Christine Angot’s voice alone was a message: What do you suspect of the daily humiliation and dog-like torment of the one who sits there day after day and writes a book? And something else was enough for the non-writing world: the writer is solely responsible for his idea, everything that flows into his text are tributaries of his own flood of thoughts.

Nora Bossong writes that she is “just a little stunned”

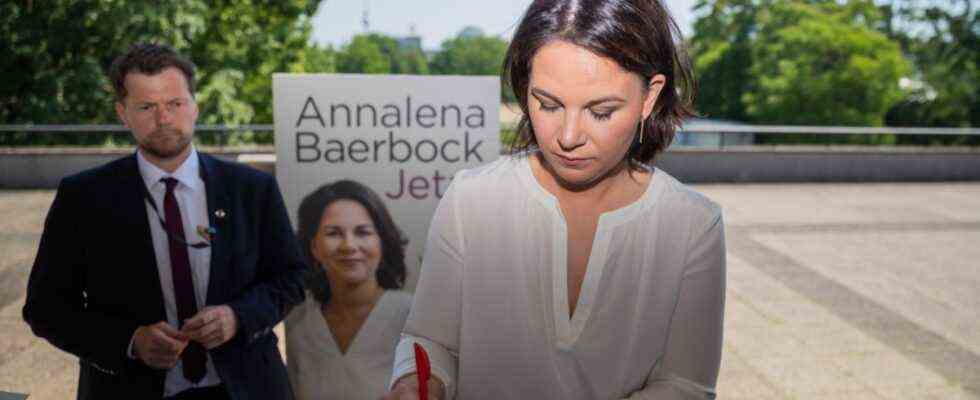

Without question, the pathos that comes along in the figure of the lonely writer, on whose shoulders at best the demons crouch, is hung. In fact, it’s a little weird. But it’s not half as funny as Annalena Baerbock’s sentence, which goes completely like this: “As the saying goes: Nobody writes a book alone.” There is a bit of a quibble in the phrase “As it is called”. Because the saying “Nobody writes a book alone” does not exist any more than there are otherwise the helpful octopus arms of a blessed writing community. And the great editors, without whom no book would get caught between two covers? Annalena Baerbock probably did not appreciate her work when she spoke of the large number of co-designers.

What should the readers think now? That literature is created in a kind of Rubens workshop with a dozen well-employed employees? That man’s ability to write books is inherently so limited that it takes a whole machine? It looks like Annalena Baerbock has hardly made friends among German writers, and if she does, Nora Bossong is not one of them. She tweeted: “Anyone who sits alone at their desk ten hours a day for years to write books is just a little stunned by Baerbock’s remarks.” And it could be that Bossong’s anger at a certain contempt for writers in Baerbock’s quote is no accident.

In terms of German politics, one has to see this in comparison with France, also with Italy or Spain, there are hardly any links left in the literature business, apart from invitations to stand around at receptions. Historians and people of age remember the times when writers not only delivered exotic external views in tea meetings with the Federal President, but also helped shape the political will. A large part of Günter Grass’ work consisted in sensitizing the SPD – first for Grass’s views, then for Willy Brandt’s policies (who, of course, was very annoyed by the vain Grass), and finally for a new culture of political speech. There was even a kind of literary language laboratory, the “Wahlkontor deutscher Writers”, in which Grass, FC Delius, Peter Härtling and Nicolas Born also tinkered building blocks for politicians’ speeches.

These authors all wrote their books alone, but part of their linguistic expertise went to the party they considered the most progressive at the time. Such fruitful societies will hardly be found in the current political scene. Emmanuel Macron quoted Walter Benjamin par cœur at the 2017 book fair. Angela Merkel had just remembered the Hessian verse “There is magic in every beginning” during the President’s inaugural visit. Doing Germany together “.

Together is a magic word in politics. Those who are in favor of joint action binds the fraying society together. If Annalena Baerbock defends herself by saying that her book is also the result of a kind of alliance of many people with lots of dear views, then that may (have been) good for her political agenda. It’s really bad for your book.

Perhaps the book “Now: How we renew our country” and its brief history of reception to Baerbock was a lesson and an occasion for contemplation.

(Photo: Ullstein Verlag)

Anyone who works as a journalist with the results of other people’s thought processes must either cite sources or have the chutzpah of a scrubber of text. When Thomas Mann had published his “Doctor Faustus”, the only way he could ward off the somewhat penetrating reenactment of Theodor W. Adorno was to publish a postscript. In order to keep the “exposure of my ignorance in the exact” as low as possible, as Mann wrote in it, he had “found a participating instructor” in Adorno. Everyone knows that Adorno bustled around Thomas Mann until he handed in that ironic and, for Adorno, somewhat embarrassing encore.

For Annalena Baerbock that is of course nothing. Her participating instructors have withdrawn her authorship without any action on their part. Unfortunately, it now looks like the book was written in full by participating instructors, and when Baerbock wanted to start writing, the brownies had already done everything. But now it should be good too. Perhaps the book and its brief history of reception was a lesson and an occasion for Baerbock to take a break – possibly even with the reading of a great work.

This week, the reading world is celebrating the 150th birthday of Marcel Proust, who over a period of thirteen years wrote a novel of around 4000 pages about how we are continually seduced and disappointed by our memories. Since the first volume was published, scientists have been digging up every word in this written monument, nurturing doubts about authenticity and then cashing in these doubts again. But what no one has ever questioned: Proust wrote “In Search of Lost Time” alone. He was there like no other: archiseul.