When Heinrich Köster set out in his Fiat 500 at the beginning of the seventies to get involved in the Bavarian academic revolution, his classmates initially declared him crazy. A Munster in Rosenheim? From the prosperous Ruhr area to the Bavarian no man’s land? To study something at the smallest technical college in the Free State – wood technology? “Nobody understood that back then,” says Köster. Half a century later, the 69-year-old Westphalian can look back on an international career: Bahrain, Egypt, Canada.

He has been back in Rosenheim for twelve years now, as the oldest Bavarian university president. This week there is reason to celebrate. The Technical University of Rosenheim is one of ten universities in the Free State that this week can look back on its 50-year history. For the anniversary there will be a big ceremony on Wednesday at the Flugwerft Schleißheim. There are representatives of the universities from Augsburg, Regensburg, Coburg, Munich, Nuremberg, Weihenstephan and Würzburg. They are all the result of an educational promise, they were all founded in 1971. How did this wave of founding come about? And where are the Bavarian universities today?

To understand why Heinrich Köster drove his Fiat 500 through Germany in the early seventies to grind wood in Rosenheim, a jump to the sixties helps. The household budget was full, Willy Brand promised education for everyone. But the university apparatus could hardly keep up. In the universities the students – almost all of them young men – quickly sat on the stairs. The minister-presidents then made a decision: the university landscape should be expanded to include so-called universities of applied sciences.

The Westphalian Köster was doing his carpenter apprenticeship at that time. That was obvious, as he came from a wood family, his parents’ carpentry shop is still there today. But NRW was practically cut down. During a tour of Europe he stopped in Rosenheim. In the pub, someone sat down with him at the table and revealed something that should change his life: that you can study wood technology here in Rosenheim. “The city was considered the Mecca of the wooden,” says Köster – and like many of its kind, it had just been promoted from an engineering school to a technical college.

This was financed from the Free State’s silverware, including the privatization proceeds from the sale of the Isaramperwerke. With success. The numbers at the new Bavarian universities rose sharply. Right in the middle: Heinrich Köster. For 50 marks a month he stayed with a war widow and helped found the Asta pub. And he sharpened. Boards, furniture, parquet, chipboard. In the end, he was allowed to put on the traditional brown semester hat and carried his knowledge abroad.

Science Minister Sibler raves about the “application-oriented teaching”

Meanwhile, the boom at universities continued. The initial 17,000 students quickly grew to more than 30,000 in the seventies, and the number doubled again by the nineties. More and more courses were added at the university. Interior design, industrial engineering, computer science. One has meanwhile grown to almost 40 courses, 600 schoolchildren more than 6000 students, and a wood technology center into a research facility with a bilingual website and Anglo-Saxon Duzkultur up to President Köster.

Students are now called students, and every third person in Bavaria is now enrolled at a college instead of a university. One in ten of the approximately 120,000 comes from abroad. Politicians are also well tried and tested in praising the practically oriented work at the meanwhile 19 universities in the Free State. If you ask Science Minister Bernd Sibler (CSU), he raves about the “application-oriented research and teaching”, the “innovation drivers” and the “exemplary transfer of knowledge”.

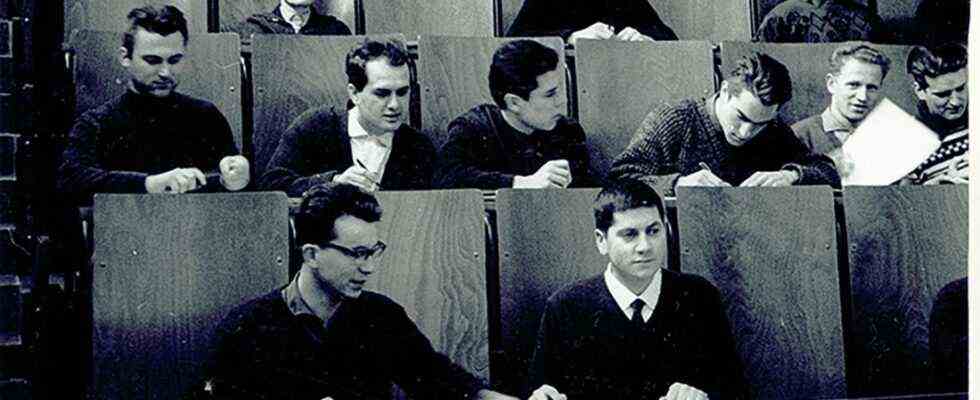

Historical teaching situation in Regensburg.

(Photo: OTH Regensburg)

For some students only second choice

The university directors know, of course, that for some students they are only second choice. The prestige still precedes the Ludwig Maximilians University more than, say, the East Bavarian Technical University. The latter also has a harder time retaining professors. Less pay and reputation for more lessons, you first have to do some persuasion. And this, although the export hit of German engineering comes from the universities: This is where the majority of them are trained.

On the way to more self-confidence, the Bavarian university reform works like soft soap. It is easier to get your doctorate, build faster, make your own decisions: there is great hope that with the reduction in bureaucracy, the sometimes dusty image of universities will also be given a new coat of paint. But political strengthening also comes with pressure. That this is worthwhile, “we now have to prove with research successes,” says Walter Schober, President of Ingolstadt University and Chairman of University of Bavaria. For this, emphasizes Heinrich Köster, the universities would have to network even more in the region.

The subject he studied at the time has now grown into a range of specializations and questions about the future. How do I panel a yacht? Can wood be built into an airport? Could Nespresso capsules one day be made from wood fiber? And maybe even clothes? It would be a breakthrough “made in Rosenheim”, which the Westphalian would definitely like.