It’s not called without reason: digging in memories. Remembering is an archaeological endeavor. Encrusted layers are broken open and what was buried comes to light. An old photograph forms the common thread of remembrance in Sinthujan Varatharajah’s essayistic memoir “to all the places that lie behind us”. There is a hint of Varatharajah’s mother’s head on it. Together with her, the reader looks at three elephants in the Munich zoo in the 1990s.

From there, Varatharajah digs into the deep layers of colonial history interwoven with the Tamil family history. Like the elephants, the family watching them was taken from their surroundings. Because of the genocide of the Tamil minority in the civil war in Sri Lanka, which was marked by colonialism, she fled to Bavaria in the 1980s. Varatharajah was born in an unnamed asylum where the family had to endure years.

Photography also served the colonial masters as a weapon of submission

Today, Varatharajah lives, writes and researches political geography in Berlin. The style of the book is unexpectedly fascinating, a mixture of theoretical references, auto-ethnographic perspective and geological language. The Western power against which the book writes is recognized in the compulsion to keep things in order: “I think that being marked on a map, being discovered and being visible can also mean a kind of imprisonment.” This is evidenced by a language that names everything from a European perspective, or a scientific documentation machine that objectifies what is seen in the colonies and, robbed of its history, has exposed it to economic exploitation.

Sinthujan Varatharajah: “To all the places that lie behind us”. Hanser Verlag, Munich 2022. 352 pages, 24 euros.

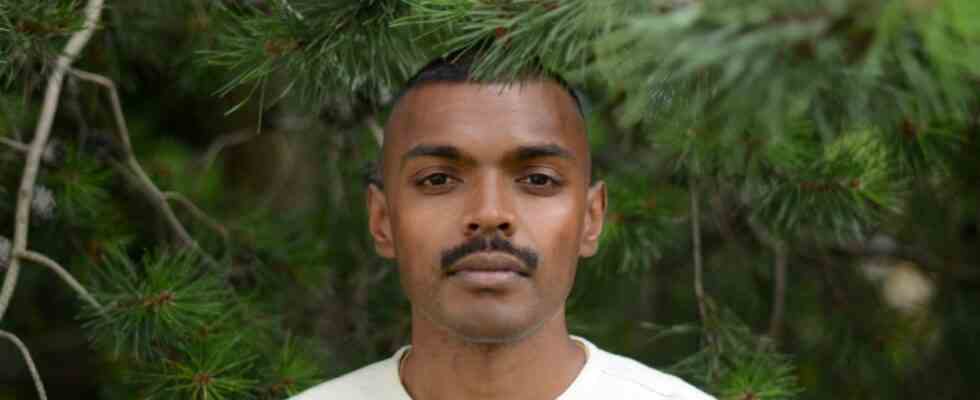

(Photo: Hanser)

Photography also served the colonial rulers as a weapon of submission. Optionally to stage the locals as “wild others” or civilizing successes. The right to the image was always in the hands of the Europeans. But when Varatharajah’s father bought a camera in 1977 and began photographing his family, he appropriated the power of the image: “With every picture of herself, her self-image in this place, in this society, in this life on earth grew.”

The book attempts to continue the line of empowerment by focusing on those who historically set the gaze, seemingly invisible behind the cameras. These shift intentions also characterize the text linguistically, if common points of the compass or country names are written in italics or binary designations of persons are avoided.

As irony would have it, the reception of the book has meanwhile confirmed his thesis. So became in one review of mirrors from Sinthujan Varatharajah and the also writing brother Senthuran one person. There it was again, the leveling of the differences beyond the European that the book accuses. On the other hand, those who are willing to look into the archives spread out by Varatharajah can learn to perceive unseen facets.