Pier Paolo Pasolini was not always as angry as in the “private writings”. In them he lashed out against consumer society, cultural decline, the increasing production of the superfluous, in short, he railed against the gradual Americanization of Italian (and Western society in general) in the 1960s. Nor had Pasolini always been a pre-modern communist. Not always suspicious of all left-wing extremists, those bourgeois children who he thought were ignorant of the reality of the proletariat, and not always skeptical of the sexual revolution (just the so-and-so many events in the society of the spectacle) and also towards the long-haired men – the conformism of the anti-conformists seemed too much to him in voguethan that he could be serious – and also in relation to abortion.

He wasn’t always the slippery movie buff like in “The 120 Days of Sodom”. And in Rome nothing interested him so much as the street urchins Borgate, of the huge shanty towns that were built without any plan or sense for the environment and even less for the urban development of the post-war period, about which he tells in “Ragazzi di vita” and in “Accattone – who never ate his bread with tears”, “Soft cheese” and “Mamma Roma”. The book and these films, they all laid the foundation for his fame.

In order to get a grip on his loneliness, the young Pasolini began to explore the big city life incognito

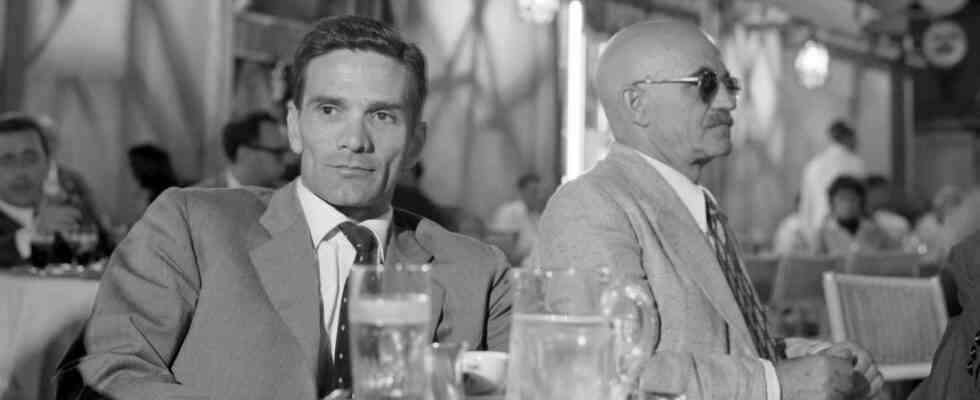

Long before Pier Paolo became “the Pasolini”, i.e. the somewhat kitschy icon with the melancholy, bespectacled face that now adorns bars and house fronts in Rome, a bit like Kafka’s in Prague and Joyce’s in Dublin, he was the budding writer quietly arrived in Rome with his beloved mother in the winter of 1949. Little is known about this Pasolini. He is now accessible to readers in “Rom, Rom”, a volume of short stories to be published by Wagenbach Verlag on March 5 to mark the centenary of Pasolini’s birth.

Pasolini had had to flee from Friuli, the region where his mother was born, to which he had withdrawn during the war because he had been reported for offenses against morality and the seduction of minors. In December 1950 he was sentenced to three months probation. The young teacher came to Rome and found accommodation in the slum, a stone’s throw from the Theater of Marcellus, the Synagogue and Piazza Mattei and the famous Turtle Fountain. He didn’t know anyone, or at least almost, lived as it was, worked as an extra at the Cinecittà film studio, did correction work or wrote little finger exercises for the “Miscellaneous” section in the newspapers. To quell his frustration and deal with his loneliness, he began exploring the city life incognito. He observed the simple people, just as he had been fascinated by the Friulian peasants – in many ways…On his forays Pasolini left the slums, took the tram or crossed the Tiber on the Ponte Sisto to reach Trastevere -Strolling around the neighborhood where most of the stories in “Rome, Rome” are set.

He knows everything.

He thinks. he doubts But he knows everything.

He knows more than heaven knows.

He would do anything for what he knows.

He puts on a fresh shirt, ties

changes his tie – and does it.

He throws the bird he is holding into the fire, takes the camera and films what everyone, whether they want to or not, understands:

the animal that uses its wings to rekindle the fire in which it burns.

“The Tiber behind him is an abyss drawn on tissue paper”

Stories, or rather fragments, one could also speak of vignettes that, magnificently illustrated with selected photographs by Herbert List and Henri Cartier-Bresson, lead the reader into a world of men, of young people who basically don’t give a damn. “The Boy and Trastevere” is about someone “dark as a violet, as dark as only the boys from Trastevere can be,” a roast chestnut seller who rips off his customers. There it says: “The Tiber behind him is an abyss, drawn on tissue paper”. And the Tiber Island lies “between the misty sky and the cadaveric Tiber”. In the tale “The Drink”, one of these boys offers the narrator a bottle of Chinotto. In “The Smooth Shark,” one of them, a cunning liar, puts makeup and perfumes on a spoiled black fish, spoiling it in order to sell it. In “A Peasant Tale” the narrator follows Romano, “who has lived among flowers for eighteen years”, who comes to Rome for the first time.

All of these texts document a city that no longer exists

In his vignettes, Pasolini delves into the rumbling stomach of downtown Rome. He describes the sounds of the city, the colors and smells. His eye and his pen work like a camera, and the future film buff is already roaming around. All of these texts document a city that no longer exists, a Rome immediately after the war. Social loneliness, the wild and untamed, also appear in them, as well as Pasolini’s human and sexual openness, which he always managed to translate into literature shortly afterwards.

On the banks of the Tiber, under the pillars of the Ponte Sisto, the children laze around or do “head and foot jumps from the bases of the pillars” into the river. They play cards in the bar on the pontoon bridge, they smoke in the auditorium of the Borgia cinema, “legs stretched out on the back of the front seat”. Little boys play with marbles on the pavement of Campo de Fiori. In the stadium – Pasolini idolized the game of football – one encounters errand boys, market traders or grocers with “face(s) stupid from bursting with health”. Here “they give vent to their Romanness”. A small red plane circles the inside of the stadium, “dragging behind it the huge flapping cloth advertising the Brilliantine Linetti”. The bends of the Tiber are “blue”, the silky smell of “fennel and rocket” fills the city. The morning sun “still smells a little like cabbage”, it is “extremely delicate, glowing” and “the air pervaded by its rays is crystal clear”. Pasolini studied when he was younger in Bologna with Roberto Longhi, the famous art historian who had once rediscovered Caravaggio: the tones on his palette resemble those of a painter, as is particularly evident in the short story “Studies on Life in Testaccio”. .

Their style is neo-realistic Dolce Vita Fellini’s (who would soon become a friend of Pasolini’s) is far from in sight. The river banks are full of weeds, mud and garbage. In the author’s imagination, the city is poor, tragic and picaresque. “It stinks of laundry hanging out to dry on the alley’s balconies, of human excrement on the stairs leading down to the Tiber.” The buildings are black, the facades of Trastevere and Testaccio sinister. In the fight for survival, the boys steal fruit. They are thin and lanky, their faces appear pale, “olive”. But Pasolini also portrays these boys in their dignity and cheerfulness. In “Blindendes Rom” they stroll, “the young, adolescent Romans along the banks of the Tiber, laughing, with the lively evening breeze on their cheeks”. His gaze is never ironic, nor mocking, he is tender and compassionate, his subjectivity is poetic through and through, inseparable from “a socio-political awareness sharpened by his own financial problems,” writes his biographer René de Ceccaty.

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Rome, Rome. From the Italian by Annette Kopetzki et al. Berlin 2022, Wagenbach. 120 pages, 18 euros.

Pasolini loved Rome like a madman. The Rome he describes in “Rome, Rome” as a special and popular capital, still proletarian and sub-proletarian, confused and chaotic, and whose protagonist is the people. He loved the Roman soul, the stoic-Epicurian in it, which was based primarily on common sense, which in turn condemned with humor everything that comes along as idealism, and also on the language, the “Romanaccio”. But from the mid-1960s his love faded more and more, until at the beginning of the following decade there was a hard separation: “Rome has changed very badly … The thing did not originate in this city, it belongs to a phenomenon of decay affecting the whole of Italian society,” he explained to the Italian daily in June 1973 Il Messagero. The city is “unrecognizable because of the massacres caused by urban planning and the cultural genocide”, it resembles the countless small Italian towns: “petty-bourgeois and petty, Catholic, stuck deep in the morass of the inauthentic and neurotic”. Here he is very far away from the collection of stories, the tender tone and this gaze, which is sometimes quite enraptured about the city and its inhabitants. But in some places the Rome of the young exile Pasolini still exists, as far as I can tell as a newcomer.

For example, on a Sunday afternoon in spring, you only have to go to the Trattoria al Biondo sul Tevere once for breakfast. You will meet families there who have come together for three, sometimes four generations, strict couples who have just come from mass, or lonely strangers. The typical Roman cuisine on offer here is excellent, the atmosphere is easygoing and the view of the Tiber, which seems quite rough from this point, is fantastic. Pasolini ate here on November 1, 1975, the day before his assassination.

Translated from the French by Miryam Schellbach.

Olivier Guez is a writer. Most recently he published the novel “The Disappearance of Josef Mengele”.