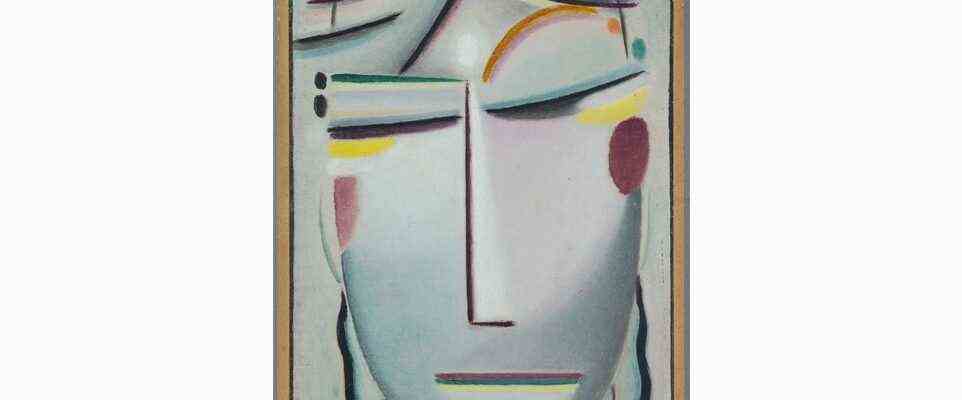

This work from the series of the faces of the Savior, created in 1921, appears relaxed, which is also reflected in the title. Alexej von Jawlensky called it “Savior’s Face: Resting Light”. The painter varied the motif again and again.

(Photo: Bernd Fickert / Museum Wiesbaden)

One expects him in Wiesbaden, wrote Alexej von Jawlensky in 1921 to the Swiss collector Karl Im Obersteg. There is much more to the short sentence than a mere message, it is the great hope for a new beginning. The painter is at a crossroads. The relationship with Marianne von Werefkin is finally at an end after decades, the common life in Switzerland in the Ménage-à-trois with the maid Helene Nesnakomoff, mother of his son, who was born in 1902, can no longer be maintained. How promising, on the other hand, is the health resort of Wiesbaden. Jawlensky’s pictures are currently being celebrated there in an exhibition at the Nassauischer Kunstverein and the Neues Museum, more than in Frankfurt am Main, Berlin or Munich, with Heinrich von Kirchhoff there is a collector and patron ready, thanks to the active mediator and organizer Galka Scheyer.

“Here one really loves and understands your art,” she writes to him. Who wouldn’t want to move to where one is understood and welcomed? Wiesbaden is the new paradise of the Russian painter.

A walk with patron Tony Kirchhoff on Wilhelmstrasse in Wiesbaden in 1922.

(Photo: Kirchhoff private archive / Mieze Binsack estate)

Jawlensky is also at the beginning of a new phase artistically. During the years in Switzerland he had started to paint heads, in series. In the course of time, the brightly colored “variations”, the “meditations” and the pastel “faces of the Savior” become to the Russians what the water lilies were to Claude Monet. He also paints still lifes and landscapes in ever new variations. At this point, however, the painter has already come a long way.

Born in Torzhok in 1864, the young Jawlensky was initially a soldier, as is customary in the family. But he is interested in art. In Saint Petersburg in 1892 he made two groundbreaking encounters. On the one hand he studied with Ilja Repin, on the other hand he met the already recognized painter Marianne von Werefkin, four years older than him, with whom he shared his life in one form or another for almost 30 years. In 1896 the two of them left Russia and with it realistic painting. Munich will be the new beginning.

The artist deals with Van Gogh

Jawlensky takes up a lot of impulses here. There is the salon that Werefkin maintains in the shared apartment on Giselastrasse, he takes courses with Anton Ažbe, he travels to Paris. He deals with Vincent van Gogh’s vibrant brushstrokes, which is clearly visible in his painting “Summer’s Day” from 1907. But Jawlensky also has Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin and the German Expressionists in mind.

The painter is not someone who would express his convictions out loud. Lisa Hohorst, who visited the artist couple repeatedly in Munich before the First World War, describes Jawlensky’s character in 1947 as follows: “Jawlensky gave the impression of a Russian grand master: he was of a natural refinement, a natural chivalry, despite all his emotional agitation a rare self-control, he always seemed balanced, spoke little, in contrast to M. v. Werefkin, who with her sparkling esprit, her intellectual charm could keep a whole society in suspense. “

Jawlensky also seems to have played the role of the dormant pole during his later famous stays between 1908 and 1910 in Murnau in Upper Bavaria, in the small villa of Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky, which the place remembered as the “Russian House”. Together with Münter and Kandinsky, Werefkin and Jawlensky promote the development of painting here. Colored areas come into play, strong contours, reminiscences of Japanese woodblock prints. The “Lady with a Fan”, which he painted in 1909, shows how Jawlensky unites all these influences and uses them to shape his painting. A strong orange-red envelops a young woman, largely clad in blue-violet, who looks down, withdrawn. In the same year the Neue Künstlervereinigung München was founded, to which both couples initially belonged; but Kandinsky left the dispute after a few years. The far bigger break comes from outside: The First World War forces Werefkin and Jawlensky, together with Helene and son Andreas, to flee to Switzerland.

The painter is plagued by money worries again and again

After these troubled years, the new beginning in Wiesbaden seems promising. Jawlensky married Helene here in 1922. Patrons are also available, with Tony Kirchhoff, with Hanna Bekker vom Rath, who founded the “Association of Friends of Alexej von Jawlensky’s Art” for the painter, who often suffered from financial worries, and finally Lisa Kümmel also entered his life. Kümmel visits the increasingly sick man every day, supports him and makes lists of works with him.

Regardless of all the obstacles, Jawlensky pushes the game of always fundamentally changing the same motifs with tiny nuances. The “faces of the Savior” differ from one another only in a few details and yet each tell new stories. Sometimes an orange square as an eye, paired with a second eye in the form of a black oval, sometimes open eyes, sometimes just lines. This is followed by the “Abstract Heads”, then, when he can hardly hold the brush because of his arthritis, the small-format “Meditations”.

The painting “Lady with a Fan”, with its flat color fields, is one of Jawlensky’s key works.

Image: Bernd Fickert / Museum Wiesbaden

Pure desolation: the “Meditation: Remembering my sick hands”, which Jawlensky painted in 1934.

Image: Museum Wiesbaden

Painted pain: The “Great Meditation: Winter Night Where Wolves Howl” was created in 1936.

Image: Museum Wiesbaden

These reflect Jawlensky’s condition. In the distant USA, Galka Scheyer struggles to find buyers for the “Blue Four” (Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Klee, Feininger) marketed by her, but has only limited success. The rise of National Socialism exacerbated concerns. In 1930 Jawlensky was excluded from an exhibition of German artists because he was Russian. He applied for naturalization, which, interestingly, was granted to him in 1934. That does not save him from being banned from exhibiting. In addition, there is polyarthritis, which is becoming increasingly noticeable. Jawlensky has been confined to a wheelchair since 1937. How this affects his state of mind can easily be seen in the “meditations”, which work like a synthesis of his life. They combine the icons of Russia with the colourfulness of Gauguin and abstraction. With just a few strokes, mostly in dark colors, Jawlenksy paints face to face. The pictures are called “Memory of my sick hands” or “Winter night where the wolves howl”. The pain is visible. The artist died on March 15, 1941 in Wiesbaden.

How he saw his work he wrote to Hanna Bekker vom Rath in 1932: “It was with me Mr. Kallei, a Hungarian, art writer, sensitive man, knows a lot. Said about my heads: very nice, you are a born colorist! “It’s not enough. I’m a religious person. My art is a prayer. Ikona.”