The rotunda of the Pinakothek der Moderne is a very special place to exhibit jewellery: abundance of light and wandering shadows literally melt matt shimmering silver pendants and set chrome-plated brass rods in dangerous lightning bolts. Therese is no better place to experience the craftsmanship, aesthetic and tactile qualities of Therese Hilbert’s jewelery art.

Red paint on the parapet of the upper gallery forms a luminous circle around which the amazing life’s work is arranged. There are leitmotifs: silver is the preferred material, sometimes similar to mother-of-pearl, sometimes high-gloss or deeply blackened. Clear forms predominate, which not only have an exterior, but also a mysterious interior that sometimes breaks out of the underground glowing red.

“Jewellery carries me,” says Therese Hilbert, meaning she carries me through life, over all cliffs. It has never been easy for the Swiss goldsmith in the male-dominated jewelry and art world. Born in Zurich in 1948, she studied with Max Fröhlich in the so-called metal class at the Zurich School of Applied Arts, which was influenced by the Bauhaus. “I grew up in an abstract world,” the artist explains in retrospect.

The exhibition begins with a silver bracelet that Hilbert forged in both directions from a square. The aim was to produce a piece without soldering. Her diploma thesis is just as astonishing: a forged silver wire that first nestles around the auricle and then spirals over the temple. These earrings were worn on one side. “We were much braver then than we are today,” Hilbert comments on her early work, which brought her a job in the workshop of the famous Bernese goldsmith Othmar Zschaler.

An apple with a real, cast-in core: Therese Hilbert was daring in the early 1970s.

(Photo: Otto Künzli)

It was even bolder to turn my back on the Swiss goldsmiths and, newly married to Otto Künzli, to start anew at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts in the jewelry and utensils class with Hermann Jiinger. That was in 1972. A year earlier, Bussi Buhs had set up a study workshop for plastics at the academy. The Swiss perfectionist released herself intuitively: She made two pairs of cherries that you can hang around your ears like children do. She also came up with half a red-skinned apple with the real core poured in as a pendant and promptly won a fashion jewelery competition in Neugablonz.

At the beginning of the 1980s, jewelry was not for the parents’ generation, but for people of the same age, for T-shirts and jeans, for the street and the music club. Hilbert makes pillow brooches, from the slits and perforations of which cotton squirts, which each wearer could soak in their favorite scent. The jewelery artist sewed pennants from the coveted, strikingly designed plastic bags from the hip Swiss department store Globus, which could then be pinned to the breast. They still look fresh and cheeky to this day.

The Swiss goldsmith Therese Hilbert was born in Zurich in 1948.

(Photo: Otto Künzli)

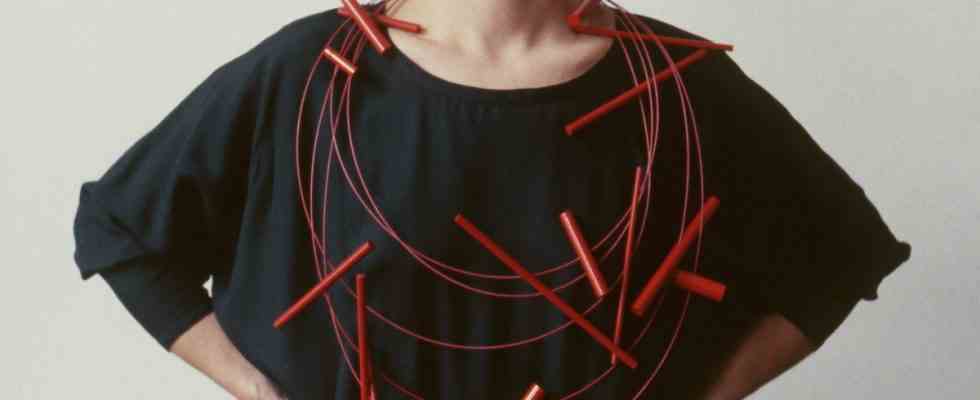

But then things got serious. Fiery red, movable rods encircle the wearer’s neck and chest in five turns, forcing her to stand upright. Otherwise, the limbs spreading in all directions can become uncomfortable. But even an approximation is ruled out by this necklace entitled “Crown of Thorns”. Hilbert goes into defensive mode in the 1980s and – inspired by museum weapon collections – puts on an arsenal of arrow-sharp brooches. Furious that the work of her male colleagues was being bought by museums and that as a woman she still had to fight for recognition. An experience with which she was not and is not alone in society.

The flat vessels brushed softly with pumice dust, which Hilbert made as pendants in the 1990s, speak a completely different, tender language. The small jugs and amphorae from the display case gleam brightly with moonlight. Worn on the body, they can be held soft and warm in the hand close to the heart. Some hollow forms are then also intended as a personal bearer of secrets.

Blackened silver and coral, this brooch is from 1996.

(Photo: Otto Künzli)

Therese Hilbert has been interested in slumbering volcanoes since the mid-1990s. She hiked them, explored them – attracted by the smells and the poisonous colors of the milky crater lakes – and always kept her eyes on the uncertain ground, collecting materials. The volcano has become the emblem of her life and jewelry. First unmistakably iconic, then sublimated abstract and finally very concrete with the use of obsidian and lava rock.

There is a pendant made of two glowing red lacquered silver discs, which, with their recesses, are reminiscent of the lava flow meandering around rocks, all the more so when the two discs shift from red to darker red when worn. Fiery tongues lie over blackened hollow forms, sulfur-yellow “deposits” can be found on the edges of oval brooches. Some hammered black silver domes look like they could rip open at any moment. At the brilliant end of the tour, a bundle of red-painted silver sparkles hangs in the display case: a symbol of the sparkling passion with which Therese Hilbert combines jewelry and life.