They are already a little theatrical at Esa: “MTG-I1 will never be seen again,” reported the European space agency a week ago. The cryptic letters stand for Meteosat Third Generation Imager. Its first model was at the launch site in Kourou/French Guiana just inside the Ariane 5 been stowed – hidden behind the steel casing of the approximately 50 meter high launch vehicle. Twelve years had the development of the first Meteosat-Third generation weather satellites. It is scheduled to start this Tuesday at 9:30 p.m. Central European Time. Satellites in the series have been geostationary at an altitude of about 36,000 kilometers since 1977, so they do not orbit the earth to take their pictures.

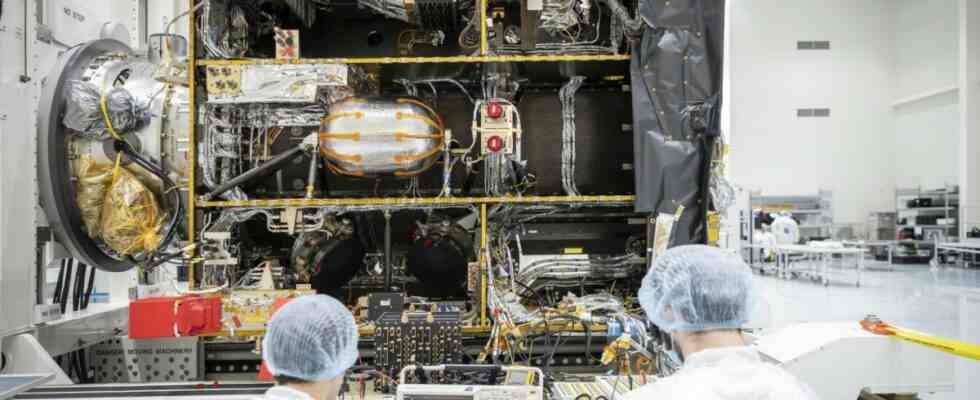

Of the eleven so far Meteosatsatellites, the four devices of the second generation are still active. The task now is to send a total of six new weather satellites into orbit in the coming years – built under the aegis of Thales Alenia Space (TAS) in Cannes, France, and the space company OHB in Bremen and Oberpfaffenhofen. The satellites are about 5.5 meters high, weigh 3.8 tons when fully tanked and are not only intended to replace the old ones. With the new aircraft, Esa and the European weather agency Eumetsat want to receive more data in the future, which should enable a more detailed and precise forecast – especially of storms.

The capital I in the name of the satellite stands for Imager, which means that these platforms are equipped with optical instruments and a lightning detector that can detect thunderstorms at an early stage. A total of 16 channels for specific spectra allow weather events to be recorded with a resolution of up to 500 meters; previously, the accuracy was only up to one kilometer. The satellite scans the whole of Europe every two and a half minutes, which is twice as fast as before. In the final phase, the flying high-tech devices will scan the entire globe every ten instead of the previous 15 minutes.

The new Meteosat generation consists of six satellites

This is also made possible by the fact that the satellites no longer have to rotate in order to have a stable position in space, as OHB manager Rüdiger Schönfeld explains. This had the disadvantage that the satellite is only aligned to Earth five percent of the time, i.e. mostly looking into the depths of space. With a platform stabilized in three axes, the optical instruments are now constantly scanning the weather kitchen. This development project “really pushed the technologies to the limits of feasibility,” says Schönfeld. The satellite is supplemented with a relay for the search and rescue service. This makes it possible to receive emergency signals from earth, for example from mountaineers who have had an accident, and to forward them to the rescue services.

To the new Meteosat system includes a total of four imager satellites, the main contractor is Thales, but OHB is supplying the platforms, among other things. Under the aegis of the Bremen-based company, two so-called sounder satellites are also being created, whose infrared instruments can record humidity and temperature values over time at different levels in the atmosphere. “We then get a four-dimensional image of the weather in our field of vision,” enthuses Eumetsat program manager Alexander Schmid. “For the first time, the entire life cycle of storms can be monitored,” he says. Since 1980, up to 145,000 people have died worldwide as a result of climate events, and most recently the damage has amounted to more than $100 billion in one year, says Schmid. It is “extremely important” to be able to make accurate predictions.

However, it will probably be 2024 before the first half of the new Meteosat generation flies. Due to the necessary tests and adjustments, it will take about a year after each launch before the additional weather data can be included in the forecast. According to Esa manager Martin Peccia, the entire program will cost European taxpayers 4.3 billion euros. Money well invested, says Peccia: “It is very important for us to ensure the continuity of this critical service for the next 20 years.”

After their deployment, the satellites land in “graveyard orbit”

Rainer Hollmann from the German Weather Service expects “a significantly better forecast”, especially for small-scale weather forecasts. On the other hand, the long-term forecast will also be “slightly better”. In addition, the data from aviation, farmers and the energy industry should provide more precise information against the background of the energy transition. Even the best weather satellites cannot prevent flooding disasters like the one in July 2021 in the Ahr Valley, but the additional data might have meant that warnings could have been warned even more efficiently. “I could imagine that you might have managed to be a little better,” says Hollmann.

The new satellites are designed for a service life of around 20 years, after which they fly from their place of use to the so-called “graveyard orbit” – another 800 kilometers further out in space. In order to be able to circle safely there, the remaining fuel is then drained. “There is currently no technology available to bring satellites back down from geostationary orbit,” says ESA manager Peccia. Although Esa is planning a mission in 2025 to tow away a disused rocket stage as a test, it is close to the earth and is to be burned up.