Doctor Liu is in an awkward position. He accidentally stumbled into a geography lesson that takes place not only at night and outside, but also with psychic participation. Animals and roots in the earth suddenly become audible, there is enormous noise, and when Liu wants to sit down briefly on a stone and rest, the supposed stone turns out to be a head. “The person to whom the head belonged cried out in pain., Doctor Liu, it’s me, your patient Lao Lin! ‘”

Instead of wondering about the incident, Liu is relieved – “finally someone he was familiar with!” Before he can talk to his patient, however, there is again a stone in place of the head, which the doctor uses pragmatically: “Without being particularly worried, he adjusted the stone with one foot so that he was more comfortable Doctor Liu tried to take things as they were. “

With this attitude Liu is not only representative of all the characters in Can Xue’s novel “Love in the New Millennium”, which has now been published in German translation. He also suggests how this extraordinary book can be read, and what is the interest of its equally extraordinary author. Can Xue describes her books as performances that she performs together with her readers. In concrete terms, this means that by refusing to accept the usual expectations of logic, coherence, linear time and “realistic” representation, it opens up the space for a collaborative process of knowledge.

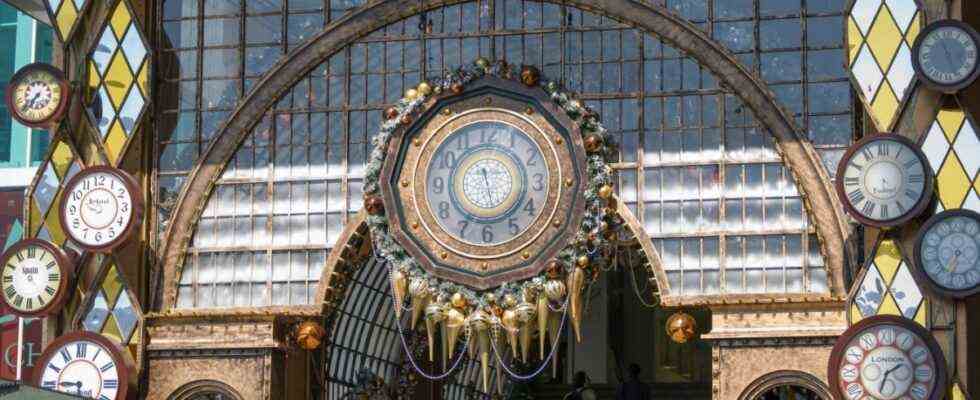

The writer and literary critic Can Xue, born in 1953.

(Photo: mauritius images / Andrew Eaton)

Xue is interested in an affective, physical, perhaps also mystical knowledge; their unusual style is an attempt to stretch the language far enough to accommodate this prelinguistic knowledge. The technique she uses for this is similar to that écriture automatique: She writes exclusively by hand, exactly one hour a day, without preparation, without a break, but above all without revising or editing. Reading your books often feels like attending a yoga boot camp: Either you have a herniated disc afterwards and never want to go back, or you are a lot more flexible and have got rid of some stuck beliefs.

“Love in the new millennium” offers a whole range of such possibilities for metaphysical loosening up. This book teaches you to read as you read it – which is only strenuous until you do it like Doctor Liu, free yourself from your own expectations, and take things as they are.

The novel has neither a plot nor a main character; laws of nature neither seem to apply in his narrative world, nor are they completely superseded. The most unusual thing is the temporality that prevails here: radio alarm clocks constantly announce the same time, events repeat themselves, the narrative jumps back years and starts again from a different perspective. At most, the characters wonder briefly and then continue, like Xiao Yuan, who returns from a business trip to her husband Wei Bo: “She looked at the clock with emotion. ‘Today is New Year.’ ,I’m sorry, what?’ They both went back to their rooms. “

Such non-sequitur jumps are, in addition to absurd dialogues, borrowings from ghost stories and fairy tales, as well as quieter, poetic passages, part of Can Xue’s style. This book is now divided into eleven chapters, each dedicated to a single figure. The people move in changing constellations through a nameless city. There is a great deal of exposure and various forms of violence in the narrated world, but apparently you don’t have to worry about the characters who can take care of themselves quite well. The narrative structure contributes to their resilience: Since they repeatedly disappear from focus and later reappear as secondary characters in the stories of others, they are never completely lost.

Can Xue: love in the new millennium. From the Chinese by Karin Betz. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2021. 398 pages, 26 euros.

Instead of a plot, this text is held together by repetitions and variations. Not only the figures, but also objects reappear in unexpected places. Bushes and shrubs grow from one story to the next. Vases, cicadas, the address 132 Binhai-Allee and a string tree repeatedly play central roles without necessarily being identical to their incarnations from a previous chapter. If you manage to free yourself from expectations of coherence and linearity while reading, then something wonderful happens: you relax. Suddenly, like an LSD trip or after a successful meditation, new connections become conceivable.

The puzzles in this book are not allegories or logic problems that can be cracked. They are more reminiscent of koans, those paradoxical riddles of Zen Buddhism, which are not there to be solved through thought, but to break open fixed assumptions of truth and lead to enlightenment. What happens in “Love in the New Millennium” is not a recognition, but a recognition. The book creates its own logic that offers all characters and objects a comfortable home. They make sense simply because they have happened before. In this way, the small scenes that deny the overall narrative create a wonderfully succinct mood.

This also applies to the characters who move through this world, as Eileen Myles, who wrote the epilogue for the American and German editions of the novel, observes: “There is no small talk, nothing phatic. Everything is always emphatic. The Surface is deep. ” In this world of unconditional affirmation of the contingent, everything is significant; chance encounters become great loves within a few lines.

“I love you too! Let me shake your hand.”

For example, when Xiao Yuan meets a blind man on one of her business trips on a train who impresses her deeply, but shortly afterwards loses sight of him again, only to be visited by the man’s brother who has been with him in her hotel room at the destination desperately looking for a long time: “‘I think that most people like your brother. He really is a special person! Me, for example, I fell in love with him straight away, honestly, in love!’ “Really? Oh, it takes a load off my heart. I love you too! Let me shake your hand.”

It is not without reason that this is reminiscent of Dostoevsky in his stormy avowal of chance. Like most Chinese authors, Can Xue is extremely well-read, has published studies on Kafka, Borges, Calvino and Dante, among others, and repeatedly emphasizes her special appreciation for Russian literature in interviews. One must think of Dostoevsky when reading this novel because his protagonists seem to have constantly broken rules that neither they nor the readers know.

This can be interpreted as a commentary on totalitarianism, especially since the text alludes to trauma in Chinese history that affected Can Xue himself. For example, daily re-education sessions take place in the prison, to which Wei Bo voluntarily goes at some point, which are strongly reminiscent of the time of the Cultural Revolution – this ideological civil war that lasted from 1966 to 1976, cost millions of lives, destroyed countless cultural assets in China and one whole “lost generation” produced. Can Xue also belonged to this group, whose parents were tortured as “reactionary intellectuals” and exiled to labor in the country. Her formal education ended when she graduated from elementary school. Her parents had been persecuted before that, during the famine that followed Mao’s insane economic policy of the “Great Leap Forward” in the 1950s. The family lived on the mold on the wall of their dorm room; Can Xue and her younger siblings developed tuberculosis, and their grandmother starved to death.

Your work is singular and literarily of higher quality than the comparable figures

So the author knows what she is writing about when she lets her characters experience extreme physical stress. However, it would be too brief to read these passages only as a political commentary on a cruel Chinese century. Because not only are Can Xue’s historical experiences of violence a secondary matter of course, they also offer access to very own forms of transcendence: “Can Xue’s work, amazingly, suggests that hunger and suffering can also make you high, visionary and even playful”, writes Eileen Myles.

Can Xue is rightly regarded as one of the most colorful personalities in Chinese literature: for years she has been considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature, mostly speaks of herself in the third person, occasionally reviews her own books and replies to interviewees who think of her work as an idea of Western world literature want to assign that it is obviously singular and, from a literary point of view, of much higher quality than all comparable figures.

“Love in the New Millennium” is actually singular, and the translator Karin Betz translates Can Xue’s mixture of weirdness, humor and poetry into German in a great way. It’s a shame that the publisher put a misleading blurb on the novel, suggesting that the main character of the text is the aforementioned Wei Bo, around whom a number of female figures are grouped. In fact, it’s the other way around: the main characters in this novel are the diverse women who are a good step ahead of the few men on their path to self-knowledge and fulfillment. To describe the narrative world as “matriarchal”, as it is also in the blurb, seems even more nonsensical: The property and power relations in Can Xue’s world correspond almost exactly to the normal patriarchal state of the real world.

It is also a shame that the publisher has not given its translator space for a foreword or an afterword with some explanations, because the novel offers an abundance of puns and references to classic topoi of Chinese literary history, knowledge of which is clearly enriching for reading. One reads this book differently, for example, if one considers the genre of “strange stories” (Zhiguai Xiaoshuo) knows, a kind of mixture of ghost story and porn that Can Xue obviously quoted; or, if one follows the Daoist maxim of the Wu Wei, of doing through inaction, which all characters in this novel practice unspokenly.

Perhaps, however, Can Xue’s novel does not need such interpretation aids at all; Just the experience of reading through this unfamiliar text form already feels like a Taoist perception exercise.